This article by ExxonKnews is published here as part of the global journalism collaboration Covering Climate Now.

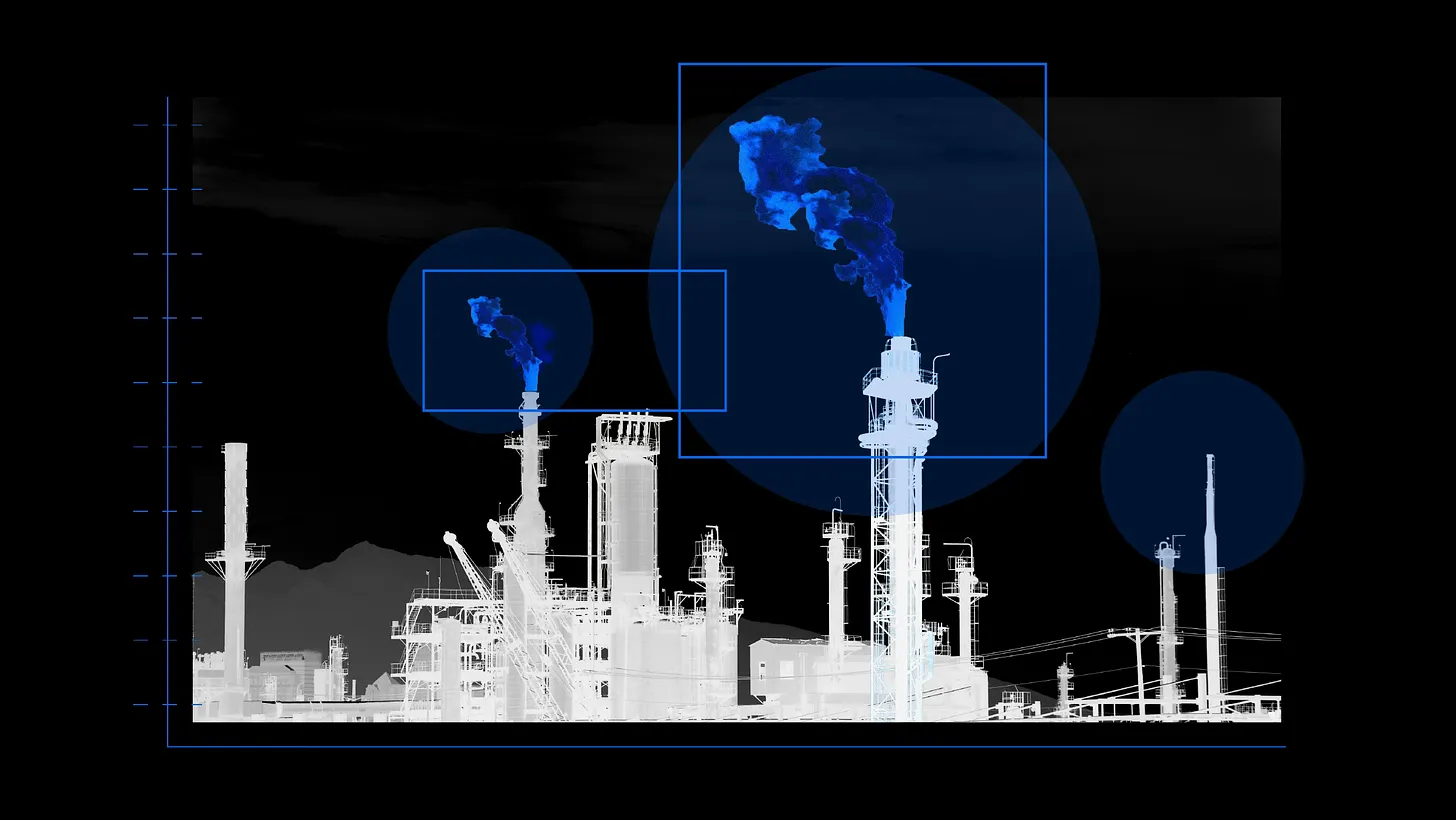

When Sharon Wilson arrives on site at an oil and gas facility in Texas, it’s the smell that often greets her first. An odor similar to rotten eggs or a mechanic shop can come from toxic pollutants emitted during fossil fuel production, like hydrogen sulfide and benzene. But Wilson is also there to capture an invisible, odorless pollutant: methane, a potent greenhouse gas that can only be seen through her optical gas imaging camera.

Wilson and her crew at advocacy nonprofit Oilfield Witness are called “methane hunters” — but she simply points her camera at an oil and gas facility and can see a black cloud on screen as the instrument picks up hydrocarbons absorbing infrared in real time.

“The oil and gas industry says ‘Look, you can see our site — you can’t see anything.’” she said. “Well, yeah, you can with one of those cameras.”

In recent years, a growing number of nonprofit organizations and non-governmental initiatives have turned to advancing technologies to document methane emissions on their own. As methane emissions pose an increasing threat to the climate amid the Trump administration’s regulatory rollbacks and attempts to gut federal emissions tracking, those groups are grappling with what their work will mean in the years to come.

Scientists and government bodies say reining in methane releases from fossil fuel facilities, which make up about a third of global methane emissions from human activity, is crucial to limiting irreversible climate change. Methane is a powerful climate pollutant — more than 80 times more potent at warming the atmosphere than carbon dioxide over the span of 20 years. Across the United States, it’s emitted from an ever-expanding web of oil and gas projects, including nearly a million active oil and gas wells, along with pipelines, compressor stations, export facilities, and underground storage and transportation lines. One of the biggest sources is abandoned coalmines and oil and gas wells, according to the latest Global Methane Tracker report from the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Although countries and companies have the tools to reduce methane emissions at low or no cost — and many have pledged to do so — the implementation of mitigation measures is “weak,” and record fossil fuel production has kept those emissions high, the IEA found. The agency further noted that “without targeted action on methane, the risks of severe climate damage increase considerably.”

Part of the problem is that methane emissions have long gone undercounted — oil and gas companies may be emitting up to three times the amount of methane estimated in records they provide to federal regulators. Under the Trump administration, those companies could be exempt from having to provide any records at all. The Environmental Protection Agency is planning to get rid of most reporting requirements under the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program, which once obtained publicly available data from thousands of polluting facilities across the country. For the first time in nearly three decades, the EPA did not publish its mandatory annual report on national greenhouse gas emissions this year.

Now, some of the third parties tracking methane emissions are optimistic that they are well primed to help fill in those gaps and work with companies to change their ways. Other watchdogs are expressing alarm over the implications of evaporating federal standards and oversight, which some say were already inadequate to manage pollution from increasing fossil fuel projects.

As the EPA stops tracking greenhouse gas emissions, state and local regulators may have no choice but to turn to independent emissions databases for information. One example is Climate TRACE, a global nonprofit coalition that uses satellites and other remote sensing technologies to provide an emissions inventory for states, municipalities, sectors, and corporations worldwide. “Climate TRACE is increasingly going to be able to continue to provide emissions estimates for every facility in America if other data sources shut down,” said Gavin McCormick, one of the coalition’s founders.

McCormick said his group works with big tech and car companies looking to reduce emissions in their supply chains, and anticipated more interest in his database from private companies across polluting sectors. “There are more and more emissions reducing opportunities that are actually really good business,” he said, adding that methane leaks in particular are an easy fix. “The ongoing increase in oil and gas has a very different carbon footprint depending on what we do with methane.”

The technology for pollution tracking is more sophisticated than ever, with new satellite programs like the Environmental Defense Fund’s (EDF) MethaneSAT and Carbon Mapper able to measure methane emissions and leaks from wide regions and specific infrastructure across the globe. At the Society for Environmental Journalists conference in April, scientists from EDF and Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) spoke to reporters about the advancing ability of those satellites to document companies’ changing methane emissions over time.

“In order to address methane emissions we needed to understand where those emissions were and how much those emissions were, and we had no data — nobody had data,” said Steve Hamburg, the lead scientist for MethaneSAT at EDF. With satellites tracking methane pollution, he explained, “we don’t have to take anyone’s word for it, we can independently validate it. Every major company knows that’s going to be happening whether they want it or not, around the world.”

Deborah Gordon, senior principal in RMI’s Climate Intelligence Program, who began her career at Chevron, said she believed better methane tracking would lead oil and gas companies to fix their leaks. “Gas is a commodity,” she said. “They don’t want to leak the product that they can sell. There’s real value in these companies understanding what they’re losing and burning up in smoke, and also reputational risk.”

Other groups in the methane tracking space are more skeptical that documenting emissions alone could lead the fossil fuel industry to adequately police itself. “[Satellite] data is sold to the industry,” Wilson, of Oilfield Witness, wrote in a blog post. “So if they were going to stop methane by using satellite data, methane levels would be going down right now, as the industry has access to the best data available. Unless we stop drilling new holes, satellites are just another delay tactic.”

The companies are “not necessarily bound to social responsibility, and never were,” said Josh Eisenfeld, oil and gas research and accountability manager at Earthworks, a nonprofit group that advocates for communities impacted by fossil fuel pollution.

Like Oilfield Witness, Earthworks uses optical gas imaging cameras to capture methane emissions and other toxic pollutants at oil and gas facilities across the country, then uses its data to submit complaints to the relevant regulatory authority. According to Eisenfeld, state regulators often have limited resources to monitor the complex web of polluting fossil fuel infrastructure in so many communities. On-the-ground monitoring can help them precisely detect a faulty point at a facility where methane is leaking. “We like to think we’re helping them be more efficient,” he said.

While Earthworks is working to alert state regulators, the group is limited in what it can do without cooperative federal oversight. The Trump administration is undoing Biden’s federal fee on methane emissions and requirements for addressing leaks and phasing out routine flaring, which would have created uniform, stricter standards across the country. “The same companies that said they supported methane rules that were introduced by the Biden administration are now silent as these rules are rolled back and as their requirements to report how much they pollute are nixed,” Eisenfeld said.

The American Petroleum Institute, meanwhile, has reversed its earlier support for the rule — calling it a “punitive tax on American energy production that stifles innovation” after it was repealed by a newly Republican-controlled Congress in February.

More than half of the hundred largest onshore oil and gas producers in the United States have no public commitments to reducing methane pollution, while others have quietly delayed or rescinded those commitments, according to a recently updated database by Earthworks and the advocacy nonprofit Gas Leaks. Exxon, for instance, dropped references to absolute methane emissions reductions in its latest corporate reporting after claiming two years earlier that the company planned to achieve an “absolute reduction in methane emissions by 70%” by 2030. “Even the commitments that they claimed in the past had no real legal requirements attached to them,” said Eisenfeld.

The gap in federal oversight could also be filled by third-party monitoring initiatives with very different motivations from those watchdogs. Oil and gas companies are now working with firms to monitor and “certify” their gas as low on methane emissions, allowing it to be sold by gas utilities at a premium. But their methodologies — which can include continuous emission monitoring systems — can vary vastly in effectiveness, depending on connectivity issues and the number and placement of monitors a firm chooses to use on site.

One of those firms is Project Canary, a leading gas certification company whose CEO has stated that “we are going to be able to solve climate change with measurement.” The company sells its own continuous emission monitoring systems to the companies it certifies.

According to two reports published by EarthWorks and environmental advocacy nonprofit Oil Change International, Project Canary’s monitors in Colorado regularly missed methane pollution events from oil and gas operations due to their placement and their tendency to be offline. Project Canary claimed it was not certifying the sites referenced in the reports. Earthworks stands by their findings, and says they are still awaiting data from Project Canary to support that claim. Earthworks also says its report appeared to prompt revisions to air quality rules in the state.

Another gas certification initiative launched in partnership between RMI and developer SYSTEMIQ, MiQ, aims to create “a financial incentive” for producers to reduce their methane pollution by generating different price levels for oil and gas based on adherence to MiQ’s standard of methane emissions management. “The future must be powered by 100% clean energy. MiQ’s mission is to reduce the climate impact of methane emissions from the oil and gas sector until we get there,” said Georges Tijbosch, MiQ’s senior advisor, at the time of its launch.

Even if methane emissions from the oil and gas sector were drastically reduced — they can’t be eliminated entirely, as methane is the primary component in so-called “natural” gas — the extraction and burning of fossil fuels creates a host of other public health and environmental hazards. Just this week, a new analysis found that Colorado oil and gas companies have secretly pumped at least 30 million pounds of chemicals into the ground over the past 18 months.

At the moment, there is a decline in pressure on the industry to curb its climate pollution in the U.S. The European Union is exploring loopholes for U.S. gas exports to comply with its methane emissions standards in order to avoid trade disputes with President Trump. The U.S. Interior Department is planning to fast track oil and gas project permitting procedures that could take multiple years to a maximum of 28 days. Even before the change in administration, oil companies headquartered in and outside the U.S. were “retiring” their climate commitments while ramping up fossil fuel production.

Eisenfeld warned that while “we need all of the tools in the toolbox to combat climate change, we also need to be honest about what each of those tools can do. Voluntary efforts by the fossil fuel industry, no matter what third party creates them, will always be limited by what the industry is willing to do voluntarily.”

Wilson, a fifth-generation Texan, worked an office job as a contractor with major oil and gas operators for more than a decade before she quit and moved to Wise County, the birthplace of fracking. She began submitting open records requests to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) — and eventually bought her own optical gas imaging camera to document the pollution coming from oil and gas wells next to homes and schools. Wilson has faced ire from the industry after speaking out on her blog against the impacts of fracking — in one case, hundreds of her private emails were subpoenaed by oil and gas company Range Resources in a high-profile defamation lawsuit against a Texas couple who accused the company of polluting their groundwater.

“I’ve been sitting on the side of the road watching oil and gas make big messes for almost 30 years,” Wilson said. “We have to continue to fight back against the industry’s ongoing propaganda about how they have reduced emissions.”

Wilson estimates having made nearly 500 complaints to the TCEQ, using the footage from her cameras as evidence. But the agency largely stopped responding to her requests, she said, even before the change in administration. The state doesn’t have a specific rule targeting methane releases from oil and gas infrastructure, and sued the Biden administration for its methane rule when it was first published.

By documenting invisible pollution, Wilson hopes to expose what she sees as the biggest impediment to action: the industry’s deceit about the harm its operations cause. “I think that most people, if their lover lied to them at this level, their clothes would be out in the front yard on fire, and I think that that’s where we need to get with the American public — they need to break up with the oil and gas industry,” she said. “The best way for them to be empowered to do that is to understand the extent of lying and to actually see the pollution they are breathing, and it’s everywhere.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts