Most of the United States’ major climate regulations are underpinned by one important document: It’s called the endangerment finding, and it concludes that greenhouse gas emissions are a threat to human health and welfare.

The Trump administration is trying to eliminate it.

Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lee Zeldin announced on July 29, that the EPA would soon publish a proposed rule to rescind the endangerment finding and allow 45 days for public comment.

A draft released by the EPA of the proposal argues that the agency didn’t have the authority to issue the endangerment finding in 2009 or regulations based on it. The draft also argues that U.S. vehicle emissions are not significant in terms of global emissions of greenhouse gases and that the costs to consumers outweigh the benefits.

These are dubious factual and legal propositions that will require deeper analysis once the proposal is officially published in the Federal Register.

Revoking the endangerment finding isn’t a simple task. If the rule is finalized, it will also trigger an onslaught of lawsuits. And revoking the finding could have unintended consequences for the very industries President Donald Trump is trying to help.

As a law professor, I have tracked federal climate regulations and the lawsuits and court rulings that have followed them over the past 25 years. To understand the challenges, let’s look at the endangerment finding’s origins and Zeldin’s options.

Origin and Limits of the Endangerment Finding

In 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Massachusetts v. EPA that six greenhouse gases are pollutants under the Clean Air Act and that the EPA has a duty under the same law to determine whether they pose a danger to public health or welfare.

The court also ruled that once the EPA made an endangerment finding, the agency would have a mandatory duty under the Clean Air Act to regulate all sources that contribute to the danger.

The court emphasized that the endangerment finding was a scientific determination and rejected a laundry list of policy arguments made by the George W. Bush administration for why the government preferred to use nonregulatory approaches to reduce emissions. The court said the only question was whether sufficient scientific evidence exists to determine whether greenhouse gases are harmful.

The endangerment finding was the EPA’s response.

The finding was challenged and upheld in 2012 by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. In that case, Coalition for Responsible Regulation v. EPA, the court found that the “body of scientific evidence marshaled by the EPA in support of the endangerment finding is substantial.” The Supreme Court declined to review the decision. The endangerment finding was updated and confirmed by the EPA in 2015 and 2016.

Challenging the Endangerment Finding

The scientific basis for the endangerment finding is stronger today than it was in 2009.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s latest assessment report, involving hundreds of scientists and thousands of studies from around the world, concluded that the scientific evidence for warming of the climate system is “unequivocal” and that greenhouse gases from human activities are causing it.

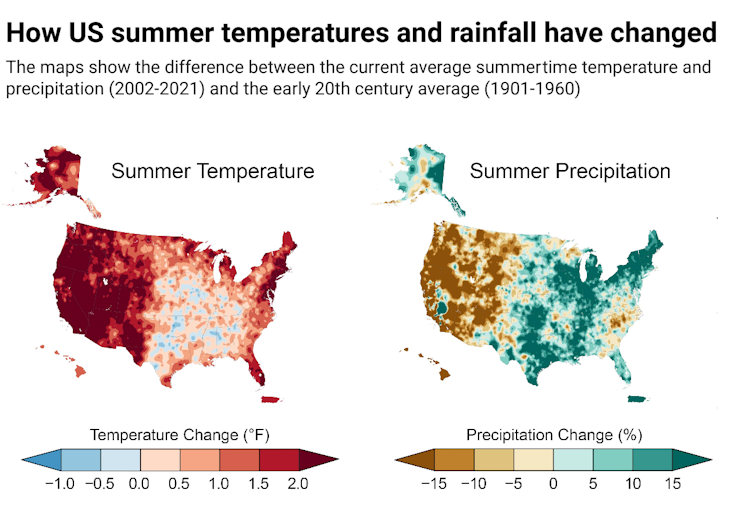

According to the National Climate Assessment released in 2023, the effects of human-caused climate change are already “far-reaching and worsening across every region of the United States.”

During Trump’s first term, then-EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt considered repealing the endangerment finding but ultimately decided against it. In fact, he relied on it in proposing the Affordable Clean Energy Rule to replace President Barack Obama’s Clean Power Plan for regulating emissions for coal-fired power plants.

Zeldin’s Cost Argument

Zeldin had previewed some of his arguments for rescinding the endangerment finding in a news release on March 12.

His first argument then was that the 2009 endangerment finding did not consider costs. However, that argument was rejected by the District of Columbia Circuit Court in Coalition for Responsible Regulation v. EPA in 2012. Cost becomes relevant once the EPA considers new regulations – after the endangerment finding.

Moreover, in a unanimous 2001 decision, the Supreme Court in Whitman v. American Trucking Associations held that the EPA cannot consider cost in setting air quality standards.

What Happens If the EPA Revokes the Endangerment Finding?

Even if Zeldin is able to revoke the endangerment finding, that does not automatically repeal all the rules that rely on it. Each of those rules must go through separate rulemaking processes that will also take months. The agency will also face lawsuits.

Zeldin could simply refuse to enforce the rules on the books.

However, a blanket policy abdicating any enforcement responsibility could be challenged in lawsuits as arbitrary and capricious. Further, the regulated industries would be taking a chance if they delay complying with regulations, only to find the endangerment finding and climate laws still in place.

A Repeal Could Backfire

Repealing the endangerment finding could also backfire on the fossil fuel industry.

States and cities have filed dozens of lawsuits against the major oil companies. The industry’s strongest argument has been that these cases are preempted by federal law. In AEP v. Connecticut in 2011, the Supreme Court ruled that the Clean Air Act “displaced” federal common law, barring state claims for remedies related to damages from climate change.

However, if the endangerment finding is repealed, then there is arguably no basis for federal preemption, and these state lawsuits would have legal grounds. Prominent industry lawyers have warned the EPA about this and urged it to focus instead on changing individual regulations. The industry is concerned enough that it may try to get Congress to grant it immunity from climate lawsuits.

To the extent that Zeldin is counting on the conservative Supreme Court to back him up, he may be disappointed.

In 2024, the court overturned the Chevron doctrine, which required courts to defer to agencies’ reasonable interpretations when laws were ambiguous. That means Zeldin’s reinterpretation of the statute is not entitled to deference. Nor can he count on the court overturning its Massachusetts v. EPA ruling to free him to disregard science for policy reasons.

This article, originally published March 19, 2025, has been updated with the EPA’s announcement to rescind the endangerment finding.

Patrick Parenteau is a Professor of Law Emeritus, Vermont Law & Graduate School

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts