This piece is copublished by DeSmog and ExxonKnews. ExxonKnews is a reporting project of the Center for Climate Integrity.

Facing a growing number of lawsuits that could hold them liable for billions of dollars in climate damages, oil companies for the fifth time in three years are asking the U.S. Supreme Court to stop the cases before they can reach trial.

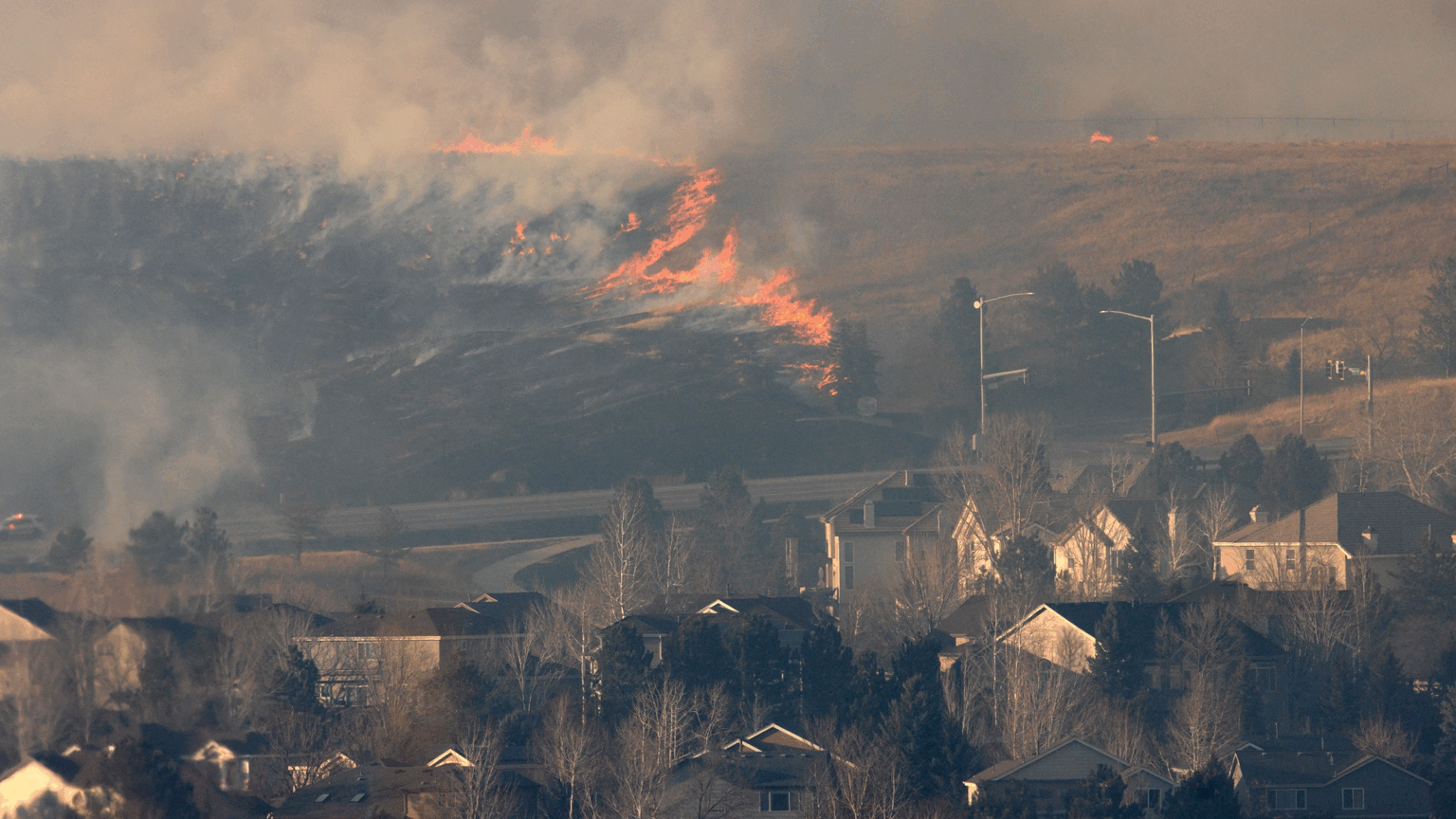

This time, ExxonMobil and Suncor Energy want the justices to overturn a decision of the Colorado Supreme Court, which ruled that a lawsuit brought against the two companies by the city and county of Boulder could move forward earlier this year. The Colorado Supreme Court found that the state law claims against the companies were not preempted by federal law. The potential stakes of the case were brought into sharp focus in 2021, when the Marshall Fire — the most destructive wildfire in Colorado state history — killed two people, burned down more than a thousand homes in Boulder County, and caused at least $2 billion in damages.

The companies have previously expressed to the Supreme Court their fear that the cases could result in “massive monetary liability.” Now, stopping them as soon as possible is “a big priority not just for ExxonMobil, but for the entire industry,” said Exxon assistant general counsel Justin Anderson at a November panel discussion hosted by the Federalist Society, a conservative legal advocacy group funded in part by fossil fuel interests.

“We’re seeing a lot more courage from people and groups and industry that’s recognizing that we have a problem, and we’re not going to wait another decade” to do something about it, he said.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts

Exxon’s latest request asks the Supreme Court to resolve what the oil giant calls “one of the most important questions currently pending in the lower courts”: whether the cases against Big Oil are preempted by federal law. It’s the same question the justices already declined to review in January, in a virtually identical petition in a case brought by Honolulu that is now proceeding toward trial.

The climate deception lawsuits filed by dozens of state, local, and tribal governments argue that Exxon and other oil and gas companies deceived the public about the dangers of fossil fuels and should be held accountable under state laws, including public nuisance and consumer protection. Many of the cases at stake, including Boulder’s, aim to recover the local costs of more frequent and severe climate disasters, like heat waves, droughts, floods, wildfires, and storms.

But the fossil fuel industry has characterized the cases as attempts to regulate interstate and even global greenhouse gas emissions through the courts, instead of through Congress under the Clean Air Act.

The oil companies’ latest Supreme Court request comes alongside an escalating fossil fuel industry offensive against the cases, which has included lobbying Congress for immunity from lawsuits entirely. Its supporters in government have also taken up the cause on several fronts, and the Trump administration is backing its Supreme Court effort.

“The only thing that has changed [since this question was last before the court] is the occupant of 1600 Pennsylvania — the facts and the law haven’t changed,” Pat Parenteau, an environmental law professor and senior fellow at Vermont Law School, said in an interview.

The Question Before the Court

Boulder argues that the energy companies’ petition comes too soon, and that there would need to be a final decision on the merits of a case to warrant Supreme Court review. Like the Hawaiʻi Supreme Court’s ruling the Supreme Court declined to review, the Colorado Supreme Court’s ruling only allows the case to move forward in state court.

“As much as defendants might not like that outcome [that Boulder’s lawsuit is allowed to proceed], their displeasure is simply not a reason to federalize a state law case,” Richard Herz, chief litigation attorney of EarthRights International, a nonprofit legal advocacy group helping to represent Boulder, said in an e-mailed statement.

But Exxon and Suncor argue that the Colorado decision “deepens a clear conflict” on the preemption question, which only the Supreme Court can resolve. “Our constitution does not allow one state or a municipality within that state to export its terrible public policy and impose that on everyone else in the country,” Anderson said at the Federalist Society panel. “That’s the clarity that we need from the Supreme Court.”

The public nuisance violations alleged by Boulder are “not because anything that’s going on in Guyana drifted over there,” Anderson later added, referencing Exxon’s operations in South America. “And if it was, Boulder wouldn’t have any right to tell Guyana not to [produce oil].”

Some lower court judges have been persuaded by Big Oil’s preemption arguments. Those rulings are mostly being appealed, but the two state Supreme Courts to review the issue have sided with the governments bringing the lawsuits.

The preemption argument was rejected last week by a Connecticut state court judge, who denied Exxon’s motions to dismiss in Connecticut’s consumer protection lawsuit against the oil giant. In his ruling, Judge John B. Farley wrote that the case is not preempted by federal law because it “seeks to regulate only the defendant’s marketing conduct” that allegedly deceived the public about fossil fuels, not to limit emissions.

The oil companies have relied heavily on a 2021 ruling from the Second Circuit in an early climate lawsuit brought by New York City, which affirmed the lawsuit’s dismissal on the grounds that it was preempted under federal law. But that ruling was “an outlier,” Victor Flatt, an environmental law professor and associate director at Case Western University School of Law, told ExxonKnews. Unlike its successors, the case was filed in federal court and did not center deceptive marketing claims as the cause of injury. State Supreme Court judges said that decision had “limited application” and that reliance on the ruling is “misplaced.”

“There may be unanimity on this panel that it makes very little sense to try to tackle the problem of climate change through dozens of lawsuits in dozens of jurisdictions around the country,” William & Mary Law School professor Jonathan Adler said during the Federalist Society event. “But the policy arguments can’t compensate for the lack of a legal basis to preempt these suits.”

Exxon and Suncor’s latest petition now claims that the lawsuits are precluded by “the structure of our constitutional system” itself — a completely new legal theory, said Vermont Law School’s Parenteau.

“The Supreme Court has never issued a decision saying, in this area of the law, the states have no authority or jurisdiction whatsoever,” he said. “They’re swinging for the fences on that one because they know that the argument that the Clean Air Act preempts is, shall we say, sketchy.”

‘A Big Priority’ for Big Oil — and Now Trump

Exxon’s Anderson made clear that he is prioritizing shutting down legal efforts by its “absolutely relentless” adversaries. “I didn’t just move my family to Texas from the East Coast to have a bunch of activists and ambitious politicians bankrupt the company,” he said during the Federalist Society panel.

“I have to win every case that is brought,” Anderson added. “They just need to find one they can get through — and that’s why it is so important for the Supreme Court to take this case.”

Oil companies “are pushing extraordinarily hard — they’re going to use every possible theory they can, they’re going to use every possible case they can” to prevent the lawsuits from going to trial, said Flatt. “They potentially face an enormous amount of damages, but it’s also about the dam bursting — if one of these [cases] goes through, it shows that it’s feasible.”

Robert Percival, a law professor and director of the University of Maryland’s environmental law program, told ExxonKnews the industry is likely concerned about the disclosure of evidence supporting the plaintiffs’ deception claims. The companies “know win or lose, the stuff that will come out of trial will make them look so bad in the public’s mind,” Percival said.

Oil companies are not alone in pushing for an end to the lawsuits — they have also solicited help from government allies. After Trump issued an executive order for the Department of Justice to oppose the cases, the DOJ submitted an unsolicited brief in Exxon and Suncor’s petition, urging the Supreme Court to throw the cases out. More than 100 Republican members of Congress also filed a brief with the court, asking the justices to shield oil companies from potential liability that “would restructure the American energy industry if not bankrupt it altogether.”

At the same time, the Trump administration is working to repeal the Endangerment Finding — the scientific basis for greenhouse gas regulation under the Clean Air Act. Doing so could undercut the industry’s core argument that the cases are preempted by federal law.

After the companies reportedly began lobbying Congress for an immunity waiver themselves, 16 Republican state attorneys general urged the DOJ to recommend legislation that would reinforce federal preemption and create a liability shield for fossil fuel companies, similar to the one gun manufacturers obtained from Congress in 2005.

“If these cases are as frivolous as the oil companies’ briefs pretend, then why in the world are you busting your butt to get a declaration of immunity from Congress?” asked Parenteau.

A Numbers Game

When Exxon last petitioned the Supreme Court to review Boulder’s lawsuit, on a jurisdictional question in 2023, its lawyers called the case an “ideal vehicle” for the justices to review because it “involves a smaller group of defendants and thus is less likely than those [other climate deception] cases to present recusal issues ” — meaning justices with financial ties to oil companies named in the other cases might not recuse themselves from this one.

Justices Samuel Alito and Amy Coney Barrett both have connections to defendants in other cases that could be implicated by a decision in Boulder’s, raising ethical questions of whether they should recuse themselves from considering the case. While Alito has a mixed history of recusing himself from climate deception lawsuits, Coney Barrett has never recused herself from one since sitting on the Supreme Court — although she regularly recused herself from cases involving Shell as a circuit court judge. To grant a writ of certiorari, the type of petition oil companies have filed, four out of nine justices will need to agree to take the case.

“If cities and counties and states are not allowed to even sue the oil companies for the damage that unquestionably their products are doing, then that means simply the public will have to pay 100 percent for all of that damage, all of the adaptation, all of the resilience,” said Parenteau.

“These are not necessarily going to be easy cases for the plaintiffs,” said Percival. “They really have to dig deep into the science of climate attribution, which has been advancing by leaps and bounds. But there’s no reason not to let them try on the merits.”

ExxonKnews is a project of the Center for Climate Integrity, which has filed amicus briefs in support of state and local governments in their lawsuits against Exxon and other fossil fuel majors, including before the Colorado Supreme Court. Emily Sanders, the author of ExxonKnews, had no involvement in the creation or filing of those briefs.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts