In a packed function room in Lagos, Nigeria, the jaunty sounds of Stevie Wonder’s ‘Sir Duke’ start to play. Then, as a giant sparkler and confetti cannon erupt, a curtain slowly parts to reveal a spinning display stacked with green, white and gold milk powder sachets.

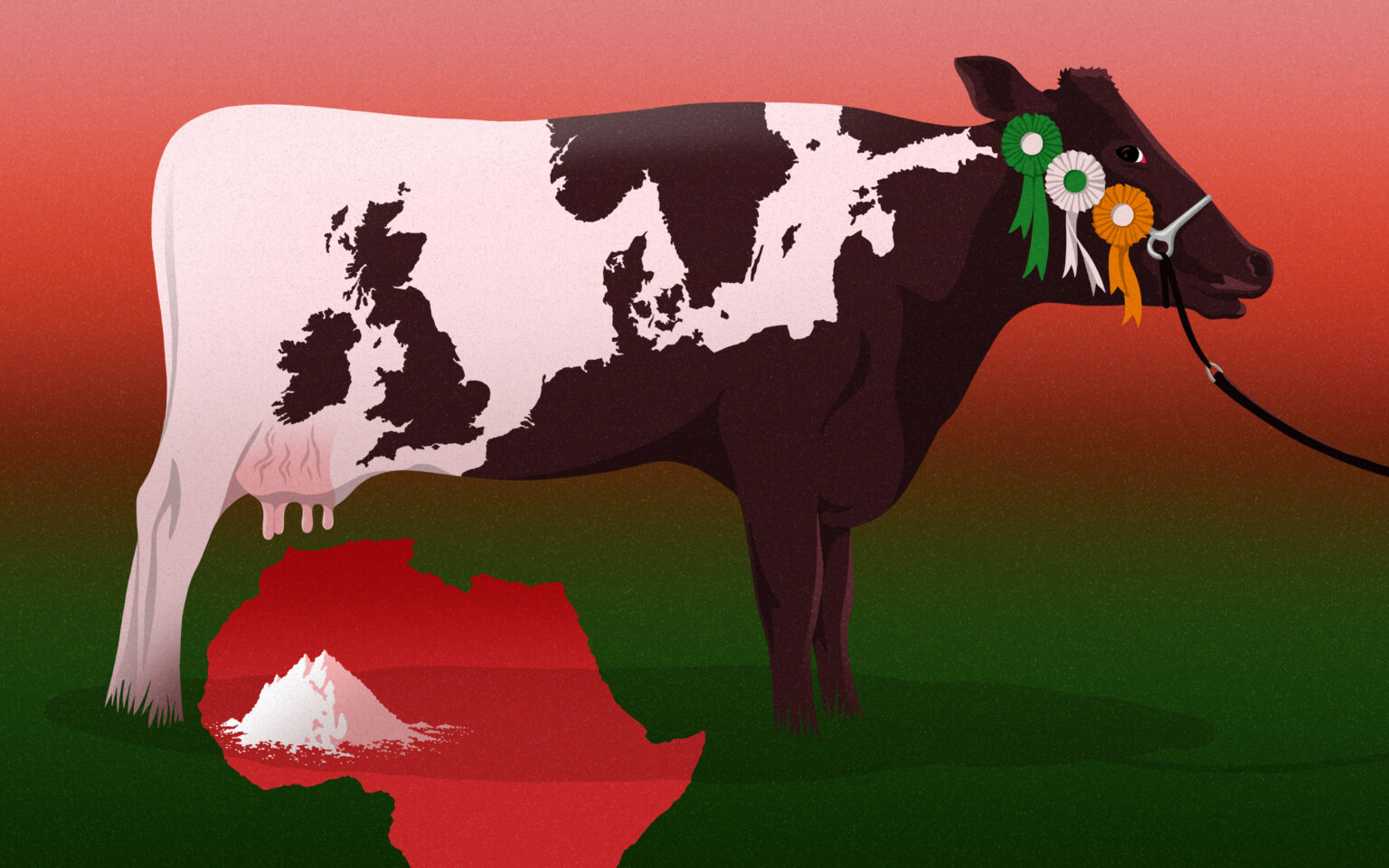

“Ornua has brought Ireland’s unique taste to Nigeria,” explains the voiceover on Channels TV network, as it presents to its 20 million-strong audience a new product, fat-filled milk powder, from the Irish dairy exporter – parent company to household name Kerrygold. Meanwhile, a news ticker running across the spectacle promotes “the uniqueness of milk from grass-fed cows”.

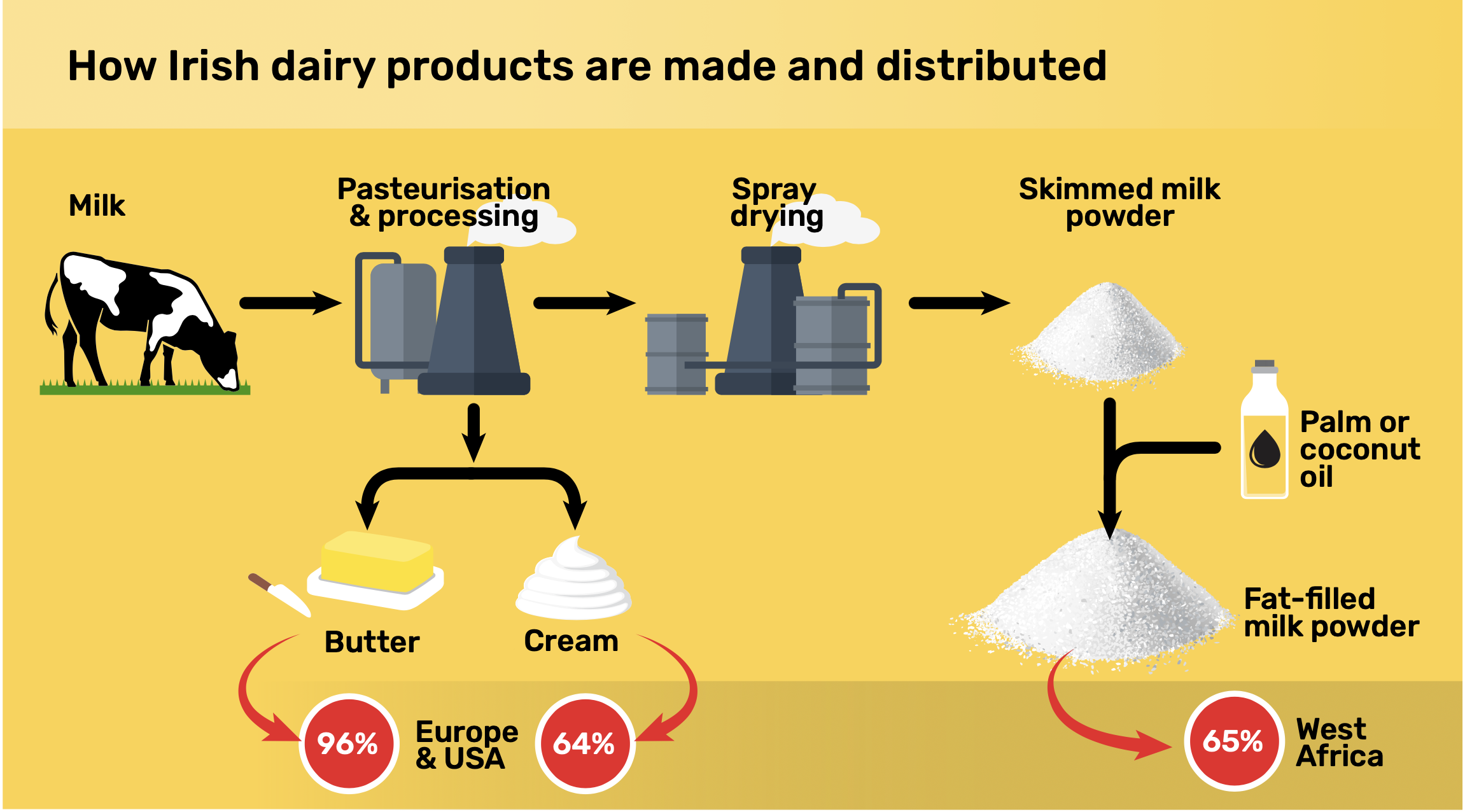

More than five years since Kerrygold Avantage landed in Nigeria, sales of Irish fat-filled milk powder (FFMP) are rising in West Africa — and highly profitable for Ireland’s dairy industry. The product is now the country’s most popular dairy export, ahead of both butter and milk, generating €825 million in exports last year.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts

Yet most people will never have heard of FFMP in Ireland, where it is sold only to businesses as an ingredient for other products, such as ice cream and baked goods. In fact, it cannot legally be described as “milk” in Europe because it does not exclusively contain milk.

Instead, FFMP is produced in factories by spray-drying skimmed milk, a waste product from butter production, and is then supplemented with vegetable fats, such as palm or coconut oil.

The vast majority is shipped outside Europe, with over half destined for West Africa.

A new investigation by DeSmog and Nigerian outlet Premium Times has traced the journey of the milk powder over 3,000 miles from Ireland, to Nigeria, Senegal and Ghana, via regional importers. Once in-country it is packaged up into large bags, tins and ever-decreasing sizes of sachet, which are sold in supermarkets, shops and on market stalls.

Cheaper than fresh milk, FFMP has a long shelf life and is marketed as a “good” source of protein – despite containing significantly less protein than whole milk powder. Mixed with water, it is poured on to breakfast cereal, or used as a tea and coffee “creamer”, as well as a base for yoghurts, drinks and desserts; its sales now rival those of the significantly more expensive whole milk and skimmed milk powders in the region.

The perception of this product as healthy and sustainable is, however, carefully constructed by companies branding and selling the product across West Africa, DeSmog’s investigation has found.

Analysis of trade and customs data has linked four major Irish dairy firms to the fat-filled milk powder trade: Ornua, Lakeland Dairies, Tirlán and The Milk Company. Between 2020 and 2024, Irish firms sold over 415,000 tonnes of FFMP to West Africa.

Documents seen by DeSmog also show that Ireland’s dairy industry is knowingly selling lactose-high products to “lactose intolerant” young people in Nigeria.

The investigation also found one FFMP brand that is supplied by Lakeland Dairies to be breaking food codes of both the EU and UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), by selling a product that contained an excess of fat, and too little protein.

Analysis of social media posts has found Kerrygold is using celebrities and influencers in social media campaigns, some of which make misleading claims. These include overstating both the sustainability and benefits of fat-filled milk powder – a product that academics have described to DeSmog as “nutritionally mediocre”.

“Most consumers in Senegal and Nigeria are unaware that FFMP is skimmed milk powder combined with vegetable fats, and is not the same as whole milk powder”, explains Papa Assane Diop from Humundi, an anti-poverty and hunger NGO in Senegal, which was the largest buyer of Irish FFMP in 2023. Market research by Ireland’s own food and drinks authority Bord Bia, seen by Irish investigative outlet Noteworthy and Premium Times, confirms Diop’s view.

The images of idyllic Irish pastures, which are depicted on FFMP packaging and adverts, are also misleading according to farmers in Ireland. It masks that FFMP is energy-intensive, derived from dairy cows farmed on lands that are highly polluted by nitrates-heavy fertiliser.

“This is an ultra-processed product that is banned from even being described as milk in the EU,” says Paul Murphy, a member of the Irish parliament and former MEP, who believes DeSmog’s findings reveal “highly unethical marketing practises” by Irish companies.

“The big agri-food companies are [the] only ones who gain – at the expense of the climate, human health and livelihoods. The FFMP exported to West Africa is putting African farmers out of business, while simultaneously driving up Ireland’s greenhouse gas emissions.”

‘Trade Targets’

A newly affluent middle class in West Africa is seen as a huge business opportunity for multinational dairy firms, and Ireland, the EU’s biggest exporter of fat-filled milk powder, is at the forefront.

Documents obtained via Freedom of Information request revealed how executives from Ireland’s Lakeland Dairies, Tirlán, and Ornua were invited on a trade mission by Ireland’s food and drinks authority Bord Bia – at a cost of €170,000 to the Irish taxpayer – in 2023. The mission marked a decade of Irish trade in Nigeria, and aimed to “increase knowledge of Irish dairy as a whole” in Nigeria and Senegal.

In one of the slideshows, attendees were told that selling FFMP products – which contain up to 37 percent lactose – could potentially have adverse impacts on the population.

“The consumption of milk among young adults is low, as many of them are lactose intolerant,” one slide notes.

Nutrition specialist Auwalu Aliyu told Premium Times the incidence of lactose intolerance, which can cause bloating, diarrhea, and stomach cramps, is high in Nigeria. “It’s a common health issue in the country,” she said.

The three Irish dairy companies, which had a combined turnover of 7.8 billion euros in 2024, enjoyed privileged access to buyers, government, and other key market players during the five-day mission, which took place in Abuja and Lagos in Nigeria, and Dakar in Senegal.

In response to a parliamentary question based on the preliminary findings of this investigation, Bord Bia said it held a number of government-to-government meetings during the visit, while Bord Bia and Enterprise Ireland met with “leading customers for Irish agri-food and agri-tech”.

Executives were also invited to a presentation on “consumer lifestyle trends” in Nigeria, which highlighted the role of branding in selling FFMP, noting that 99 percent of customers now buy branded milk powder.

“The importance of brands and brand-building in Nigeria, even among lower social classes,” was critical, one slide noted.

“People tend to trust social media and celebrities more than trained professionals,” confirms Abiola Olaniran, a lecturer in food science and nutrition at Landmark University in Kwara State, Nigeria. “In food science and nutrition, this is known as a food fad. It is a trend driven by marketing rather than evidence.”

In another slide, industry executives were told: “Keep in mind, Nigeria consumers are aspirational. Brand is a key proxy for communicating on these attributes.”

Bord Bia has previously noted the “difficulty in differentiating high and low quality FFMP”, adding that “having more branded products with information on provenance and specifications can support the differentiation of our quality product”.

The same presentation notes that West Africa’s fast-growing population, described in the slideshow as “more mouths to feed”, is a driving factor for growth in FFMP imports. Urbanisation was cynically referenced as “easier to access mouths.”

The trade mission was hailed a success by industry. According to a press release on Ireland’s government website, Bord Bia clients met with over 300 “trade targets”, concluding there is a “significant potential” for Irish agri-food sales in West Africa.

‘Embodiment of Harmony’

To make the most of market opportunities in West Africa, Irish dairy companies are running campaigns on social media, which in some cases are spreading misleading narratives around the nutritional value and sustainability of fat-filled milk powder.

DeSmog and Premium Times analysed hundreds of posts by the three leading FFMP brands in West Africa, on Facebook, X, Instagram, and TikTok between 2022 and 2024, and found that manufacturers frequently overstate the health benefits and environmental impacts of their products.

The posts analysed focused on the product’s nutritional value, ability to reduce dairy’s environmental footprint, and potential to make children sharper and more active.

Kerrygold Nigeria promotes all its products as sustainable, claiming in one X post that its dairy “reduces its environmental footprint, while also providing nutritious foods and livelihoods around the world” and that “Kerrygold Avantage Milk is an embodiment of [nature’s] harmony”, which guarantees “rich, creamy goodness always”.

Ornua, which produces Kerrygold FFMP, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. However, Barry Newman, the then head of Ornua North and Central Africa, spoke about sustainability at the launch of Kerrygold Avantage FFMP in Nigeria in 2019.

He said that Kerrygold Avantage FFMP was “always going to be sourced on the island of Ireland which has a long long history of milk production” and that “the palm oil that is used in Kerrygold will be from responsibly sourced palm oil producers which constitutes 20% of the world’s palm oil production”.

Miksi, a major fat-filled milk powder brand that is supplied by Lakeland Dairies, among others, makes a number of bold claims about its nutritional value, including that it has “all the right nutrients you need to be physically and mentally fit at all times”. Another brand, Cowbell, which bought at least 23,000 tonnes of FFMP from Lakeland Dairies between 2021 and 2024, claims its product is “high in protein which aids in brain development” and helps “kids stay strong and active”.

All the brands analysed by DeSmog fortify FFMP, a widely used and accepted way to add vitamins and nutrients to food. But experts contacted by DeSmog were unaware of any in-depth research into the nutritional value of different varieties. “It’s a bit of a black box,” says Emma Feeney, assistant professor at University College Dublin’s school of agriculture and food sciences. “There’s not a whole lot on it. Maybe because people [in Ireland] just don’t eat them [FFMP] to the same extent as butter or cream.”

Other nutritionists warn of the negative impacts of the palm and coconut oils, high in saturated fats, which replace the dairy fats in FFMP. These vegetable oils “have no health benefit but potentially negatively impact […] the overall diet,” says Dr Shireen Kassam, an NHS doctor and director of Plant-Based Health Professionals UK.

Kerrygold Nigeria also claims that Avantage FFMP is “nourishing”, “nutritious”, and a “good source” of protein, despite some FFMP brands containing up to three times less protein than whole milk powder. Some of these posts are targeted towards parents of young children, who they claim will be kept “active and healthy”, with “ sharp and active” brains.

We have absolutely zero health outcome for this product

Dr Shireen Kassam, an NHS doctor and director of Plant-Based Health Professionals UK

“We could be having healthier sources of protein and fat that we know are associated with reduced risk of chronic disease and promote longevity, whereas we have absolutely zero health outcome data for this product,” points out Kassam.

EU regulations state that fat-filled milk powder should contain a minimum of 23 percent protein and a maximum of 30 percent fat. Packaging analysed by this investigation showed that Miksi’s FFMP, sold in Nigeria contains only 10 percent protein and 35 percent fat. Kerrygold Avantage was found to meet these requirements.

According to a report by Paris-based Agriculture Research Centre for International Development (CIRAD), about 30 percent of FFMP products in West Africa do not meet international labelling standards.

“It’s clear that these are by-products,” said Christian Corniaux, a researcher at CIRAD. “They are poor quality and that’s why it’s cheap.”

Around 80 percent of Nigerians consume some type of milk powder, including FFMP, at least twice a week, according to the trade mission presentations seen by DeSmog.

Jean-François Grongnet, retired professor of agronomy at Agrocampus Ouest in Rennes, France, believes the product is “nutritionally mediocre” at best. “Saying that it has high nutritional value, well, that’s the language of marketers who want to promote the product,” he says.

Tins of Kerrygold Avantage sold in supermarkets depict a glass of milk against a background of sunlit green pastures and beyond that, the sea. Grongnet suggests that this gives consumers an impression that it is a pure milk product. “It’s misleading,” he says.

Most consumers in Senegal and Nigeria are unaware that FFMP is skimmed milk powder combined with vegetable fats, and is not the same as whole milk powder, according to Papa Assane Diop from Humundi.

Diop says this is because FFMP’s French-language labelling is inaccessible to consumers in Senegal where only a quarter of the population speaks French. “Not all Senegalese people can read [French], and even when they can the information is written so small that you can’t make it out,” he says.

Companies “highlight what they want people to see,” Diop adds.

Lakeland Dairies and Tirlán did not respond to DeSmog’s multiple requests for comment.

Lakeland Dairies states on its website that its FFMP is “a staple in global markets due to its quality, consistency, flavour and functionality”. Tirlán also states that its product “is designed to offer an affordable alternative source of dairy nutrition without compromising on taste and texture”.

Shunning Fresh Milk

In Ghana, which imported over 4,000 tonnes of fat-filled milk powder from Ireland in 2024, experts say milk powder consumption has become normalised through an extensive and long-running marketing campaign by multinationals.

“When European companies started exporting they also started advertisements on televisions, billboards and a lot of other promotions in communities,” recalls Dr Mavis Boimah, a Ghanaian researcher at Germany’s Thünen Institute.

A question to the Irish parliament (Oireachtas) based on DeSmog’s findings revealed that Bord Bia has spent a total of over €80,000 on a joint campaign with Ornua centered around World Milk Day. The campaign included partnerships with social media influencers, who were filmed making food and drink using Kerrygold Avantage FFMP.

European dairy companies have identified a receptive market in Nigeria’s fast-growing population, which is projected to reach over 400 million by 2050. Increasing urbanisation, and increasing access to imported FFMP, have also been identified as drivers for growth – 54 percent of Nigeria’s population live in urban areas today compared to 35 percent in 2000.

Aliyu Ilu is the chief executive of Little Acres, a five-hectare dairy farm in Abuja, Nigeria. He says Nigeria’s “very small” dairy industry faces many challenges from “electricity to transportation to the high cost of feed for the cattle.”

Nigeria’s cow herds produce around 600,000 metric tons of milk annually, fulfilling 35 percent of the country’s demand.

In contrast to intensive agriculture in Europe, which is heavily subsidised through Europe’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), Nigerian farming receives little in the way of government funding. The vast majority of Nigeria’s dairy is produced by smallholders and pastoralists, who are contending with everything from climate complications to infrastructural issues and bandit attacks.

“We are advocating for the consumption of fresh milk,” Ilu from Little Acres said. “Sometimes, people are shocked to hear you can consume directly.

“People say powdered milk is better because of what they have read, or seen on TV or on social media.”

Premium Times interviewed a number of dairy producers and consumers who said they preferred to buy dried milk powder sachets instead of fresh or raw milk.

“People in Nigeria are not used to raw milk,” said Hamisu Tukur Buratai, chief executive of Arwaski Farms in Nasarawa, a northern state neighbouring Abuja. “They are not aware that one can actually consume it. What they know is powdered milk.”

The sophisticated ad campaigns targeting aspirational Nigerians appear to have made their mark. One consumer described it as “quite primitive” to drink raw milk, compared to condensed and powdered options.

Jenifer Igberase, a milk trader in Wuse Market, Abuja, Nigeria says FFMP sells faster among retailers in rural parts of the country. “Miksi is most consumed by poor citizens in the northern part of the country,” she says.

Although raw milk can be safe to drink, scientists recommend it be pasteurised or sterilised before consumption by boiling, to kill any bacteria in case of contamination.

Diop from Humundi said misinformation on social media is overstating the benefits of foreign milk powder, in contrast to fresh milk. “This creates a false perception among West African consumers, turning them away from fresh milk, which is wrongly perceived as ‘dangerous’,” he says.

‘Success Story’

Despite the concerns of West African consumers, nutritionists and pastoralists, in Ireland, the milk powder industry is betting big on an ongoing demand for its dried products.

“A lot of the public just see butter and cheese and think, that’s the dairy industry,” said Conor Mulvihill, director of Dairy Industry Ireland, at a May conference on milk drying technology held in Cork.

“We are no longer a dairy industry, we’re a nutrition industry,” he said. “We think it’s a fabulous success story for Irish farmers,” he added.

There’s another story that the industry tells. In response to DeSmog’s findings, Ireland’s Department for Agriculture, Farming and Marine (DAFM) said Ireland’s carbon footprint per unit of milk was “one of the lowest among milk-producing countries” due to its “grass-based” production system.

This common industry claim of sustainability is contradicted by a 2017 study, commissioned by the European Parliament, which revealed Ireland to have the highest greenhouse gas emissions per euro of output.

Dairy production is polluting in other ways, too. Ireland’s Environmental Protection Agency highlights that agriculture not only accounts for 37 percent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions, but is also a major nitrous oxide and nitrates polluter.

Nitrous oxide is a potent greenhouse gas – with a global warming impact 265 times higher than carbon dioxide – while nitrates leach into soils and water bodies, leading to algae blooms and harming aquatic life. Methane is the most prevalent planet-warming gas due to the large size of the dairy livestock sector, which in Ireland increased by 60 percent between 2010 and 2022.

Not all farmers in Ireland consider its intensive farming model a “success story”.

“The problem is that some of the dairy production systems that we have go beyond what the ecosystems can carry, in terms of water quality for example,” says Fergal Anderson, vegetable farmer and member of Ireland’s grassroots farmers group Talamh Beo.

Bord Bia claims that Ireland produces enough food to feed 25 million people – five times its own population. However, Anderson says that this narrative does not represent reality: “We’re actually polluting our own environment in order to feed the profits of corporate companies that want to export into third countries.”

A spokesperson for Ireland’s Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (DAFM) said: “Ireland is a small open trading economy and Irish dairy products are exported to around 140 countries around the world, including markets in Africa,” adding that West Africa is a market which presents significant opportunities for Irish drinks, seafood and dairy companies. They added: “The placement of product on the market is a commercial decision for companies to make in accordance with the applicable legislation and market demand.”

“I think most farmers wouldn’t be happy to think that FFMP is where their milk ends up […] that it’s actually undermining the work of a farm family in another country,” adds Anderson. “But the corporations don’t care about that.”

Aliyu Ilu, chief executive of Little Acres farm in Abuja, Nigeria, agrees.

“Fresh milk is more nutritional compared to powdered milk, but we often meet with resistance,” he said. “We’re competing with multinationals to win consumers’ trust.”

Editing by Hazel Healy

This joint investigation with The Premium Times in Nigeria was co-published with The Journal in Ireland.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts