Blackstone, a U.S. private equity firm run by a Trump-donating billionaire, is building a gargantuan £10 billion AI-ready data centre in the UK with a fleet of backup diesel generators so big that it could produce enough electricity to power three million UK homes.

The “hyperscaler” supercomputer campus in Blyth, Northumberland – a crown jewel of the government’s freshly-announced Artificial Intelligence (AI) Growth Zone in the North East of England – will also be adjacent to a major oil and gas terminal, which one expert has warned “may be a strategic choice”.

“Diesel is one of the dirtiest fuel sources, emitting hazardous pollutants and huge quantities of carbon dioxide emissions. Tech companies have no excuse, they have the cash and the know-how to find clean solutions to their huge power needs,” said Jill McArdle of the renewable energy campaign group Beyond Fossil Fuels.

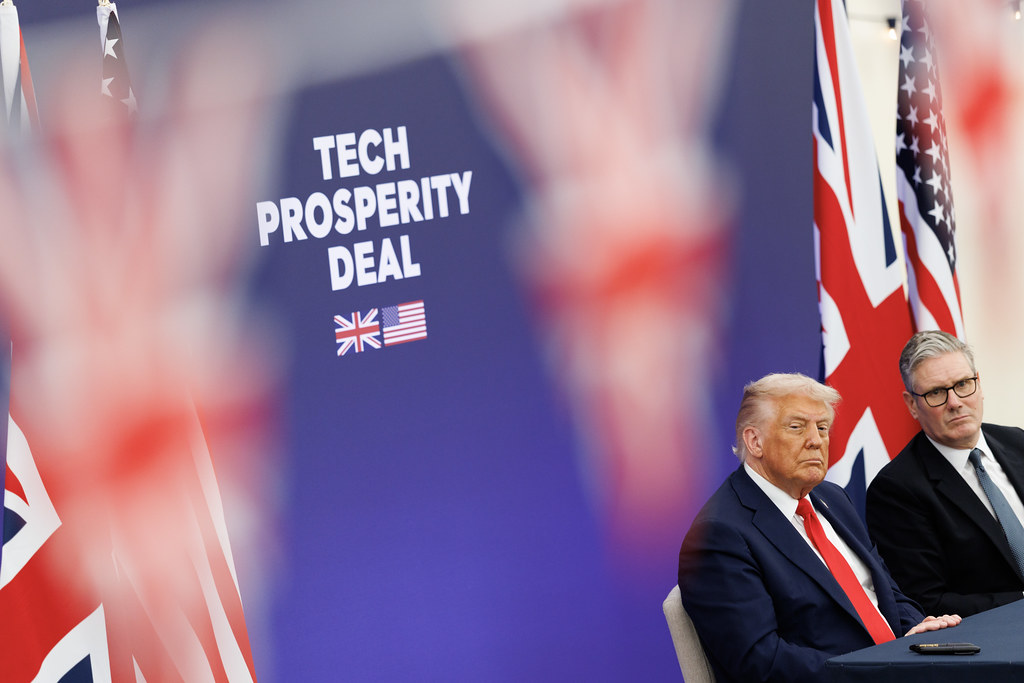

Blackstone, which has already invested $25 billion (£19 billion) in fossil fuel-powered AI in the U.S., pledged over £100 billion of investment in UK assets the same week that U.S. President Donald Trump and Prime Minister Keir Starmer announced a ‘Technology Prosperity Deal’.

The company’s CEO, Stephen Schwarzman, who has personally donated at least $3 million (£2.25 million) to Trump’s political campaigns, sat next to Starmer at last week’s royal banquet hosted for the president at Windsor Castle. Blackstone also donated $1 million (£750,000) to Trump’s inauguration campaign.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts

Planning documents reveal that Blackstone’s data centre campus in Cambois, Blyth, submitted by its subsidiary company QTS, is slated to have 580 diesel generators capable of producing a combined 3.93 GWTh, more than the total energy output of the Sizewell B nuclear power plant. If all of these generators were operating full time, they would produce about 4 percent of the UK’s entire electricity output.

While the diesel generators are only expected to run in limited circumstances, and at full capacity in emergencies, the planning documents acknowledge that “the increase in frequency of extreme weather events” due to climate change will lead to more generator use, and as a result will lead to “higher carbon emissions during operation”.

The application’s sustainability report even lists the generators as one of the centre’s “measures to mitigate the effects of climate change”.

These revelations have raised concerns that high-emission data centres in the UK will end up using ever-increasing amounts of fossil fuels due to extreme weather events that data centres will have in part created.

The average data centre uses enough energy to power roughly 5,000 UK homes, and between 11 million and 19 million litres of water per day, the same as a town of 30,000 to 50,000 people. There are 480 data centres in the UK, with another 100 planned for the next five years.

Pierre Terras, a campaigner at Beyond Fossil Fuels, added: “On top of fuelling the environmental crisis, it is outrageous that the richest companies in the world would be allowed to build new fossil fuel infrastructure and increase emissions while other key industries and households are being asked to make efforts towards decarbonisation”.

The documents further detail that Blackstone’s diesel generators “may have additional run hours based on emergency operation where the utility supplies to site fail” – which may potentially include times when the UK’s notoriously backlogged energy grid cannot provide power to the site.

“New data centres must not be allowed to use diesel generators. Even if these generators are supposed to only run in ‘emergencies’, they can often be turned on during any situation of low power on the grid,” McArdle said.

‘Data Doomsday’

Data centres, which are vast warehouses full of linked-up computers, require massive quantities of water and energy to function. A query in ChatGPT requires about 10 times the computing power of a standard Google search.

Data centres therefore currently belch out between 2.5 percent and 3.7 percent of the world’s carbon footprint – more than the entire aviation industry.

That footprint is projected to expand exponentially. The International Energy Agency forecasts that the energy requirements of data centres will quadruple by 2030 – to nearly as much energy expenditure as Japan. The UK’s National Energy System Operator (NESO) says that, by 2030, data centres will guzzle 7 percent of Britain’s entire energy output.

Researchers from Loughborough University have warned that by the end of this year the world will approach “data doomsday” when renewable energy sources will be unable to meet the demand for data centres. If the same rate of growth continues through to 2033, the researchers warn that data centres across the globe will demand more power than all the electricity currently generated on Earth.

Fintan Slye, the chief executive of NESO, told The Guardian that, even before Labour announced its plans for an AI boom, the UK was already at the “outer limit of what’s achievable” in terms of its planned renewable energy development.

Diesel Backup

While diesel generators, which have long been a regular feature of data centre campuses, are technically classed as “backup” or “emergency” power sources for when others fail, they can guzzle formidable quantities of fuel on demand, and could be run more frequently as grid reliability issues become more pressing.

In Ireland, where the government has recently announced that it is not meeting its climate targets and data centres consume a fifth of the total electricity, operators have already begun to rely more heavily on backup fossil fuel power.

The Journal reported that – between 2019 and 2024 – Ireland’s data centres, facing energy grid constraints, belched out 135,000 tonnes of CO2 from “backup” generators commonly fuelled by diesel – as much as running 33,750 cars for a year.

Though some data centre operators in the UK have begun transitioning their sites to alternative backup fuels, including hydrogen fuel cells and biodiesel derived from plants, planning applications are still being made for a data centres with a large number of backup diesel generators.

The original planning application for one of Amazon Web Services’ proposed data centres – a hyperscaler in Didcot, Oxfordshire – detailed plans to build 52 backup generators as well as capacity to hold 950,000 litres of diesel on reserve.

Meanwhile, several UK data centre operators have been preparing to rely more on diesel generators for some time. When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, American data centre operators Equinix and Digital Realty openly stockpiled diesel for their UK data centres in the event of a power cut-off, with Equinix reporting to the Financial Times that it had enough for a week of continuous data centre operation.

Generator providers have tried to capitalise on this shift. Nicole Dierksheide of generator provider Rehlko argued in a technical publication this August that “grid limitations” have meant that “diesel generators, long considered a reliable fail-safe, are becoming even more essential, not just as a stop-gap in emergencies, but as a critical piece of a broader energy strategy.”

Terras finds these developments concerning. “Big Tech is acting like a vampire. The truth is that current data centre plans are a fundamental threat for Europe’s clean energy transition,” he told DeSmog.

Gas-Powered Robots

The Blackstone data centre in Blyth is one of several supercomputer campuses planned for the North East’s AI Growth Zone, which will include “Stargate UK”, an immense AI infrastructure project involving U.S. AI company OpenAI – the creator of ChatGPT – U.S. chip-maker Nvidia, and British data centre operator NScale.

OpenAI and Nvidia, which each donated $1 million (£750,000) to the Trump inauguration ceremony, have both expressed interest in building data centres powered by fossil fuels.

In the wake of last week’s Stargate UK announcement, Nvidia founder and CEO Jensen Huang told The Times that he is “hoping that gas turbines can also contribute” to the sources of energy for UK AI. The comment was an echo of one made by a senior Nvidia director at a U.S. energy summit in April, who announced to a room of oil and gas executives that powering the company’s data centres with fossil fuels is “on the table”.

OpenAI’s U.S. Stargate Project site in Texas, which the company says will become one of the largest data centre sites in the world, is installing off-grid gas turbines to power its operations. The plans match the intentions of its Trump-donating CEO Sam Altman, who said in a U.S. Senate hearing in May that “in the short term, I think [the future of powering AI] probably looks like more natural gas”.

Nvidia declined to comment. NScale and OpenAI were also approached for comment.

This comes amid reports of an explosion of interest among UK data centre operators for building their own gas plants and hooking them up to the country’s established gas network.

Future Energy Networks, which represents a consortium of gas distribution networks, told The Times in April that it had fielded “more than 30 inquiries” from data centre operators in the previous six months alone.

Proponents of building dedicated off-grid gas plants at data centre sites in the UK include the Tony Blair Institute, a Labour-leaning think tank with close ties to Trump-supporting U.S. tech billionaire Larry Ellison. The institute argues that dedicated “modular” gas power sources will be needed to provide reliable energy to data centres as a “bridging measure” to give time for the UK’s renewable energy networks to develop.

This “solution” is an import from the U.S. – the world’s top producer of liquified natural gas. In July, President Trump lauded the development of data centres using fossil fuels while flanked by oil and gas executives.

Recently, U.S. and UK tech companies have begun pressuring the Labour government to embrace off-grid gas in Britain. In a June meeting of Labour’s AI Energy Council –which includes Google, Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, UK chip designer ARM, and American data centre operator Equinix – ministers were asked to consider “temporary on-site generation, including natural gas fuel cells” as an “interim measure” to avoid delays in connecting data centres to the grid.

While Google told Politico that it did not contribute on this topic at the meeting, Equinix confirmed that it does support “on-site gas to power solutions”.

Critics are quick to point out that such bridging measures could swiftly overwhelm climate targets. Eamon Ryan, former climate minister of Ireland, told the Financial Times that running data centres on gas was “not viable because that kills our planet”.

A Side of Oil?

While the government’s announcement of the North East AI Growth Zone calls the region Britain’s “largest source of low carbon and renewable energy”, it is also an oil and gas hub.

Blackstone’s data centre is situated roughly 1.5 kilometres from the Port of Blyth, which has a berth for receiving oil tankers and storing fuel. The nearby oil and gas terminal is owned by GEOS Group, which markets itself as the “UK’s leading marine gas oil supplier”, and receives shipments of oil from Aberdeen and Immingham.

DeSmog understands that there are no plans currently to store or transport diesel from the port to the Blyth data centre. However, the planning application details that “there is a possibility that the Port of Blyth will be used” and that “necessary infrastructure improvements will be sought that allow the smooth flow of goods to and from the Port of Blyth.”

Even if the data centre doesn’t directly connect to the port, it is only a 10 minute drive away from the GEOS terminal on current roads.

The planning documents say the site will store only 48 hours’ worth of diesel fuel in case of “extreme emergency”. Beyond that, the data centre would need to access other sources.

Louis Goddard, a partner at Data Desk, a global oil and gas industry research group, told DeSmog that “running 500 of the site’s 580 diesel generators, roughly the number designated as primary backup for the site, for just 24 hours would consume a massive amount of fuel”.

He added: “Ensuring rapid access to such a large volume of diesel would require significant logistical work. In this context, the data centre’s location across from a fuel import terminal with nearly 100,000 barrels of storage capacity may be a strategic choice. The GEOS Blyth terminal’s capabilities allow it to transfer large volumes of diesel from sea tankers to trucks”.

The Race for Renewables

The Labour government insisted to DeSmog that it is “making sure the race to harness AI’s economic potential does not come at the expense of the climate”, particularly through its nuclear deal with the U.S..

It added that “renewable energy will be a key component in powering the North East AI Growth Zone”, and that it will “ensure the pipeline of data centre projects is matched by the energy capacity needed”.

Campaigners warn, however, that even if the Blyth data centre and Stargate UK are connected to renewable power infrastructure, the projects will be sucking up clean energy earmarked for other sectors – unless these companies invest in their own renewable energy generation.

It’s understood that the site will draw on renewable power from its connection to the National Grid substation, including existing hydropower from Norway and an offshore wind project.

However, there don’t appear to be detailed plans to construct renewable power sources specifically for the project.

The planning application states that the project “will look at opportunities to implement renewable or low-energy solutions,” though does not detail the scale or nature of that intended investment.

Terras of Beyond Fossil Fuels told DeSmog: “Big Tech is monopolising existing renewable energy for the AI race. Its thirst for energy makes clean electricity scarce, and increases its costs for essential sectors like health, education, heavy industry and even for households – ultimately delaying the phase out of fossil fuels and delaying the clean energy transition”.

Oliver Hayes, head of policy at Global Action Plan, which campaigns for more regulation of data centre energy and water consumption in the UK, has cautioned that new projects are being “waved through by central government” even when there is a “glaring lack of assessment of their environmental impact”.

Hayes told DeSmog: “Data centre developers must be compelled [by the government] to disclose their full environmental impact – including downstream emissions resulting from their energy use – and to invest in new renewables at least equivalent to their total footprint.”

Terras believes responsibility falls on the companies building these energy-guzzling supercomputers. “Big Tech companies are the wealthiest in the world,” he said. “They have the means to secure their own new additional renewable energy which matches their consumption and does not jeopardise Europe’s climate objectives nor the economy.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts