“Pollution is everybody’s business,” Imperial Oil, Exxon’s Canadian affiliate, wrote in a 1970 report, “because essentially all of it results from the activities of men working to satisfy the needs and desires of men.”

Fast forward over a half century and Imperial’s old argument is taking a new form. Today, ExxonMobil is seeking to upend how carbon emissions are accounted for — by changing the rules of the game.

An ExxonMobil-backed initiative, Carbon Measures, is pushing to reshape how the world does the math on climate change. Their system, outside analysts point out, leaves consumers holding the bag.

Meanwhile, ExxonMobil also is waging a legal war against moves to entrench the system most companies currently use to report their greenhouse gas emissions, arguing it creates a “policy of stigmatization” of Big Oil.

The way the Carbon Measures coalition, a group with 23 member companies including energy, finance, and industry heavyweights, wants to run the numbers, critics say, all liabilities for fossil fuel emissions would flow away from suppliers and towards customers — to each individual person. The buck would stop not at the top, but at the very bottom, landing on each and every consumer and dispersing responsibility as widely as possible.

That means shifting big burdens “onto individuals who lack the tools, authority, and data” that big polluters have, according to the commercial bank watchdog group BankTrack. This month the watchdog called on Banco Santander, one of Europe’s largest banks by assets, to drop its support for Carbon Measures.

Creating a competing system to track climate pollution could erase the advances already made with the current system, said BankTrack deputy director Ryan Brightwell, and end up reducing transparency.

“There’s been a lot of work and a lot of progress over a period of many years to get to a position where there’s relative agreement on the system,” Brightwell told DeSmog. “To risk cracking that open at this point in the climate crisis, that’s quite alarming.”

Carbon Measures argues its system for tracking emissions allows consumers to choose lower-emissions products. “We are focused on reducing the carbon intensity of the products responsible for the majority of global emissions,” Carmen San Segundo, Carbon Measures’ head of global communications, said in a statement to DeSmog, “and our members believe this will require a more precise carbon accounting system and effective policy.”

ExxonMobil did not respond to a request for comment.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts

Darren Woods, ExxonMobil’s CEO, has said that Carbon Measures shouldn’t be seen as a delay tactic because the new plan can co-exist alongside today’s widely used carbon reporting system, supplied by Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol. “You can do this in addition to that,” Woods told Bloomberg in a November interview.

But in October, the same month that Carbon Measures first launched, ExxonMobil also sued to bring an end to California’s climate disclosure laws. The oil major argued that the law compels the company to fully report its emissions in line with the GHG Protocol system in violation of the company’s right to free speech.

“In its public advocacy, ExxonMobil has consistently argued that those frameworks send the counterproductive message that large companies are uniquely responsible for climate change,” the company wrote in its October 24 complaint, “no matter how efficiently they satisfy societal demand for energy, goods, and services.”

Lisa Sachs, director of the Columbia Center on Sustainability Investment, called Exxon’s argument “a transparent delay tactic.”

“The bottleneck to decarbonization is not improper carbon accounting. It’s the failure to implement well-known, technologically ready, and financeable system transitions,” Sachs said. “Disclosure and accounting debates have diverted time, attention, and political capital away from those real solutions; this latest initiative just adds fuel to that fire.”

Gone in a Puff of Accounting Smoke

While the specifics remain in early development, Carbon Measures’ approach represents “a significant departure from established carbon accounting frameworks,” according to the major law firm Covington, which published a guide to the coalition’s proposal at the end of 2025.

Baked into Carbon Measures’ model is the idea that when someone buys a product, they take on all of the pollution that comes with it.

That’s a big break from the world’s current standards, which call on each company to disclose all of the ways it contributes to pollution: from its own activities, from buying energy, and from the products it sells. The idea is that tracking all three categories gives a more complete picture of a given company’s impacts.

Embedded in that system is the idea that maybe both buyer and seller have some sort of responsibility that can be shared — meaning that both should have an incentive to act.

ExxonMobil and other critics of that system see that as a serious flaw. If responsibility were borne by both sides, that’d be a problematic “double counting,” the thinking goes.

Carbon Measures’ “ledger-style” system solves this conundrum by treating pollution as a liability that polluters can transfer from seller to buyer.

“If you are buying a tonne of steel, you need to understand how much carbon went into producing that tonne of steel so that when it’s sold, you’re not only selling the asset of the steel but you’re selling the liability — so to speak — of the carbon emissions that go along with it,” Amy Brachio, Carbon Measures’ CEO and the former global vice chair for sustainability at accounting consultancy EY, told FinTech Magazine.

Carbon Measures argues that approach gives consumers the ability to “reward” less polluting options.

“A global ledger-based accounting system would improve the quality of product-level emissions data, allowing markets to identify and reward low-carbon production throughout the entire supply chain,” Carbon Measures’ San Segundo told DeSmog. “Accurate and verifiable data would also allow policymakers to set product-level carbon intensity standards, creating a level-playing field and providing the right incentives for businesses to compete on innovation and low-carbon production.”

But there’s a big benefit to having one gold-standard reporting system instead of a bunch of competing ways to run the numbers.

“When everyone relies on one credible global framework — rather than competing systems — it brings clarity to markets, builds trust, and helps low-carbon products scale faster, accelerating real progress on climate goals,” a GHG Protocol spokesperson told DeSmog. “The way forward is alignment.”

Plus there’s a big question that remains unanswered when following the logic of the system Carbon Measures proposes. What happens for the buyer, at the very end of the line? If all that liability winds up handed off to just a regular person, someone who doesn’t keep a set of climate books or have any obligation to start, do the liabilities just … disappear?

“It remains unclear how E-liabilities transferred to individual consumers (e.g., drivers or homeowners) would be tracked or managed over time,” Covington analysts wrote.

There’s a “core tension,” they added, with using a liability tracking system that “could fragment accountability for companies earlier in the value chain whose actions have the highest impact on aggregate emissions.”

ExxonMobil’s Bane

Today, over 20,000 companies use the Greenhouse Gas Protocol’s framework to report their emissions. The organization touts a 97 percent adoption rate among disclosing S&P 500 companies, making its system the most widespread in the world.

For decades, the GHG Protocol has offered three basic stats companies can track, reflecting the different ways companies contribute to the world’s greenhouse gas pollution. It labels their emissions Scopes 1, 2, and 3.

The first bucket, Scope 1, are pollution sources that companies directly own or run — say emissions from company vehicles — while Scope 2 emissions come from the electricity or energy companies buy offsite. Finally, Scope 3 is where companies report everything else — including “use of sold product.” That, for an oil giant, means counting the impacts of every gallon of gasoline, diesel, or jet fuel they’ve sold.

Scope 3 emissions are the bane of fossil fuel producers, chemical manufacturers, steel, cement, and major agricultural companies. They reveal the climate-altering impacts of the products those companies sell — and it’s not a pretty picture.

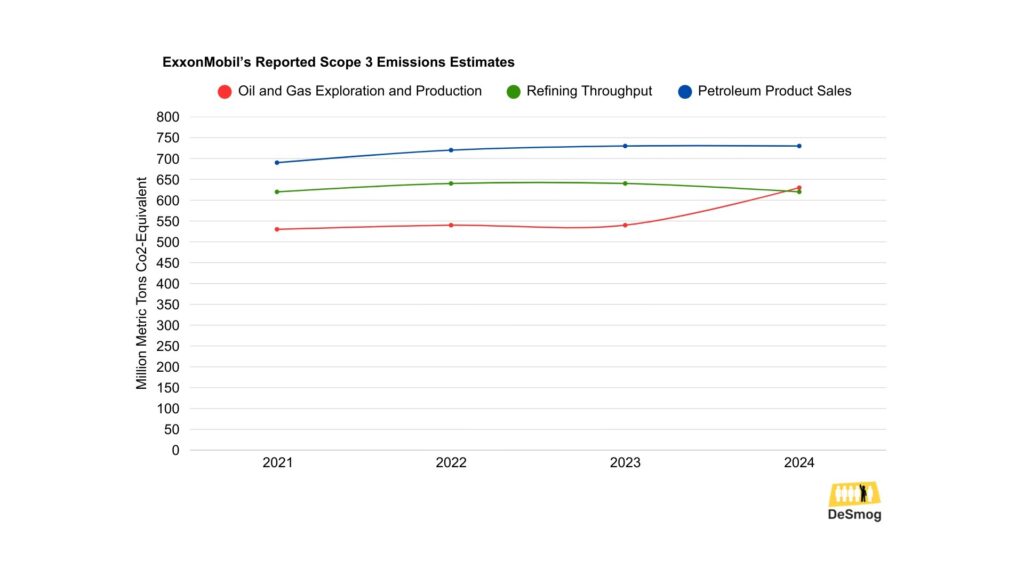

ExxonMobil, for example, has seen its own reported Scope 3 figures largely increase since it first began making numbers public in 2021. That’s especially when it comes to the emissions from the company’s oil and gas exploration and production activities, the company’s most profitable segment.

Note: ExxonMobil currently “chooses not to report on the full range of Scope 3 emissions estimates called for under the GHG Protocol,” the company noted in its October legal complaint challenging California’s mandatory climate emissions reporting laws. That means these numbers do not reflect the company’s full Scope 3 emissions, and cannot be compared to estimates prepared by companies that fully follow the GHG Protocol’s standards. They are provided here only to illustrate how ExxonMobil’s own reported figures have changed over time. Image Credit: DeSmog. Data Source: ExxonMobil’s annual climate and sustainability reports.

Independent estimates reveal that ExxonMobil single-handedly drove 2.76 percent of all carbon dioxide emissions from 1854 to 2023, a report last year from Carbon Majors found. That lands ExxonMobil among the top five all-time biggest contributors to the climate crisis, alongside “the former Soviet Union,” “China (coal),” Saudi Aramco, and Chevron.

ExxonMobil’s 2023 climate “progress report” spends nearly a full page critiquing the GHG Protocol framework and Scope 3 reporting. The document argues it “provides limited insight for a company like ours into how it might substantially lower its emissions, short of shrinking, discontinuing operations, or outright divesting operations.”

In other words, the obvious conclusion from looking at Scope 3 data is that the most effective way for energy companies to curb emissions is by moving away from producing fossil fuels.

Instead, ExxonMobil prefers to focus on how it’s cutting its own fossil fuel pollution, allowing the company to argue that its emissions are falling even as it remains deeply committed to producing more oil and gas.

In 2021, Woods testified before Congress, touting emissions cuts at ExxonMobil sites, which he described as the company’s “own” emissions. “With respect to emissions, ExxonMobil has already reduced its own greenhouse gas emissions by 11 percent between 2016 and 2020,” Woods testified, “and has set new plans for further reductions through 2025.”

A Long History of Avoiding Blame

In the business press, ExxonMobil’s support for Carbon Measures has been received, as Bloomberg put it, as “a willingness to engage in ideas to reduce emissions” and “a departure from its historical stance, which has included advertorials sowing doubt about climate science that ran in the 1980s and 1990s.”

But a closer look shows that Carbon Measures’ approach is a continuation of one of the longest-running strategies in ExxonMobil’s playbook — focusing on consumers’ responsibility for oil pollution.

For decades, the companies that make up ExxonMobil today, including Exxon, Mobil, and Canada’s Imperial Oil, pushed the idea that pollution is demand-driven.

“As individuals, we may not approve of each and all of this multitude of activities,” Imperial Oil’s 1970 report continued. “Yet as members of the society which sanctions and encourages them, we must accept responsibility for all the consequences, both the desirable and the undesirable which include the pollution caused by the improper disposal of the inevitable waste.”

That messaging shows up again and again in the company’s documents related to climate change and air pollution, from the 1960s through the 2020s. DeSmog has collected examples from ExxonMobil reports, speeches, Congressional testimony, and advertisements in the timeline below.

Timeline of Events – (Click arrows to browse)

From the 1960s through the 2020s, ExxonMobil highlighted consumers’ responsibility for climate change and oil’s air pollution, as illustrated in this timeline.

In 1998, shortly before the merger of Exxon and Mobil, Mobil CEO Lou Noto addressed climate concerns at an employee forum. There, he offered rough numbers showing the massive impact of shifting responsibility to consumers. “Our customers using our products probably count for 95 percent of those emissions,” Noto said, calling the remainder “the five percent that we’re responsible for.”

The same pattern can even be seen in the company’s advertorials. In their landmark 2021 study, climate disinformation researchers Geoffrey Supran and Naomi Oreskes found, as they put it, “ExxonMobil advertisements worked to shift responsibility for global warming away from the fossil fuel industry and onto consumers.”

The researchers found that internally, ExxonMobil seemed more likely to use phrases that suggest pollution is driven by supply, rather than demand, in contrast to the company’s public stance.

And of course, oil and gas companies aren’t simply passive sellers. The industry has worked hard to entrench demand for fossil fuels, most recently by marketing natural gas power to data centers at the heart of the artificial intelligence (AI) boom.

Today, ExxonMobil is continuing to pour money into projects that will produce oil and gas for decades to come.

In early November, Carbon Measures and the International Chamber of Commerce put out a “call for interest” for accounting experts to help develop the details of the new guidelines. Carbon Measures announced its first round of appointments on January 19, with more expected later this quarter.

The new accounting standards, if they attract sufficient corporate backing, are expected to roll out sometime between 2027 and 2030.

Sachs, the Columbia climate finance expert, emphasized that we already know how to effectively cut carbon pollution: starting with clean-energy standards, electrification mandates, and measures that phase out fossil fuel demand. But, she noted, oil companies have consistently opposed those types of policies.

She told DeSmog, “No one should mistake Exxon’s support for disclosure frameworks as an effort to solve the climate problem.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts