Dennis Avery may have done the fact-challenged (yes, again) WaPo columnist George Will one better by actually admitting he’d “misstated” that CO2 levels at Mauna Loa were declining (when they were, in fact, quite clearly rising), but the remainder of his column was so error-filled that I thought it deserved another look.

Take the first half of the piece, in which he approvingly cites Australian – and Oxford-trained – research physicist Tom Quirk to make the jaw-dropping argument that natural climate variability, and not anthropogenic activity, is to blame for elevated atmosphere CO2 levels. A quick look at Avery’s list of citations informs us that Quirk’s article appeared in a recent issue of Energy and Environment, a “peer-reviewed” journal curated by Sonja Boehmer-Christiansen, which does not inspire great confidence in its scientific rigor.

Starting from the premise that radiocarbon-labeled CO2 takes several years to migrate from one hemisphere to the next, Quirk argues that the absence of a lag between the observed variations in CO2 levels in the two hemispheres implies that fossil-fuel emissions are absorbed locally.

Since roughly 95 percent of all anthropogenic CO2 is emitted in the Northern Hemisphere, there should be a time difference between the variations observed at the Mauna Loa station, in the Northern Hemisphere, and the Antarctica station, in the Southern Hemisphere.

Not being a climate expert but sensing that this reasoning was deeply flawed, I contacted an actual scientist, David Archer from the University of Chicago (and a contributor to RealClimate), to get his input. He was kind enough to furnish me with the following explanation:

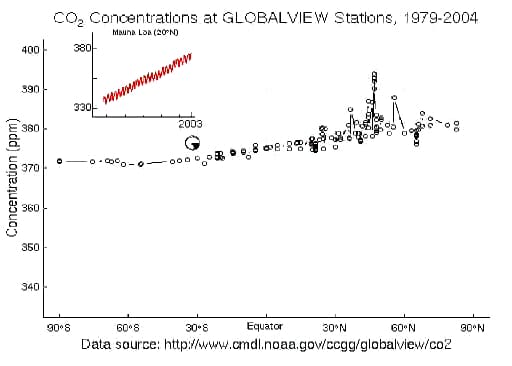

“The 14-C, and other tracers such as radioactive krypton from nuclear fuel reprocessing, show that there is a time constant of about a year for mixing between the hemispheres, not several years. I’m attaching an animated plot of the atmospheric CO2 concentration as a function of latitude [see the video below]. There’s a huge seasonal cycle, particularly in the northern hemisphere where most of the land is. Just eyeballing the plot, it looks to me like there is a higher average concentration in the north than in the south. What we’re looking for is on the order of 1 or 2 ppm higher in the north, if it’s going up by about that much per year and the southern hemisphere is one year behind. The data have been analyzed in greater depth to try to figure out where the “missing sink” carbon is going, and the canonical conclusion is that there is a sink in the northern high latitudes of about 2 gigaton C per year, but it could be in the tropics. I don’t think there is any room in the data to say that there is no northern hemisphere fossil fuel source at all.”

(For a more current version of the data Archer cites, check out this NOAA website about GLOBALVIEW.)

I decided to look into a few of his other citations, seeing as they were pulled from Science, to evaluate the basis for his claim that CO2 lags temperature. (You’ll forgive me for omitting the third listed citation, another article taken from Energy and Environment.)

To be clear, the data from the Vostok ice core in Antarctica does show that ice ages are initiated by small variations in the planet’s orbit – these can include changes in its eccentricity, tilt, or precession (for more, see this Wikipedia article about Milankovitch cycles). The variations prompt an initial warming, causing CO2 to be released, which, in turn, leads to more warming – an effect known as forcing.

Yet scientists also know that these changes are insufficient to account for the wide temperature fluctuations we’ve seen in the historical record. That means something else – let’s say anthropogenic emissions – must be helping to push the process along. Which is exactly the point Hubertus Fischer and his colleagues make in the 1999 Science article Avery cites (sub. required):

In what surely must be a freak coincidence, Nicolas Caillon and his colleagues, writing in a 2003 issue of Science, reiterate the same point:

Finally, the situation at Termination III differs from the recent anthropogenic CO2 increase. As recently noted by Kump (38), we should distinguish between internal influences (such as the deglacial CO2 increase) and external influences (such as the anthropogenic CO2 increase) on the climate system. Although the recent CO2 increase has clearly been imposed first, as a result of anthropogenic activities, it naturally takes, at Termination III, some time for CO2 to outgas from the ocean once it starts to react to a climate change that is first felt in the atmosphere. The sequence of events during this Termination is fully consistent with CO2 participating in the latter ~4200 years of the warming. The radiative forcing due to CO2 may serve as an amplifier of initial orbital forcing, which is then further amplified by fast atmospheric feedbacks (39) that are also at work for the present-day and future climate.”

Avery concludes by citing data that indicate that ocean surface temperatures have stopped increasing since 2003. Like most skeptics, he seems unwilling to accept the fact that climate science is not always a black and white affair – in other words, that it is absolutely normal to see slight variations in the year-to-year record. As an environmental economist, you would think he’d be used to seeing noise in the data. (Looked at in the aggregate, of course, the trends are clear, but skeptics conveniently choose to ignore this.)

He attacks Josh Willis, an oceanographer with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, for being a “loyal bureaucrat” that refuses to accept the cold, hard truth. Not that he needs any defending from me: You can read his own take on the supposed controversy in an article he titled “Is It Me, or Did the Oceans Cool? A Lesson on Global Warming from my Favorite Denier.”

Needless to say, the other experts Avery approvingly quotes in the article – Roger Pielke, Sr., and Kanya Kusano – are both ardent skeptics. I guess it’s time for Dennis to change his theory.

Go here to find out more details about DeSmogBlog’s monthly book give-away.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts