What a difference a year can make. While the consensus on the Hill may not have grown stronger in the interim—I’m looking at you, House Republicans—the American public seems to be increasingly wising up to the idea that global warming is, in fact, a real threat and not some nefarious liberal plot to deprive it of its God-given right to pollute.

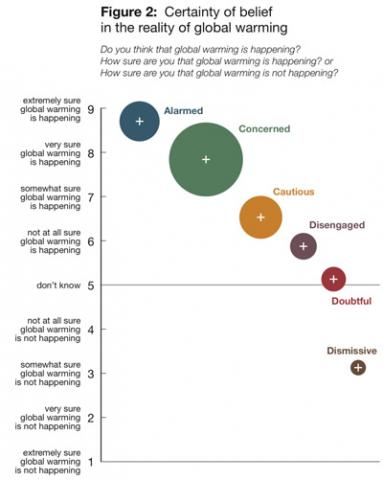

That is the principal finding of a new survey, entitled “Global Warming’s Six Americas,” that was released this past week by the Center for American Progress. The survey, which the authors describe as an “audience segmentation analysis,” splits the American public into six distinct groups based on their level of engagement with global warming: alarmed, concerned, cautious, disengaged, doubtful, and dismissive.

The authors polled 2,129 American adults in the fall of 2008 on a variety of issues related to global warming, including risk perceptions, policy preferences, and values.

The results indicate that a slight majority of respondents (51 percent) are either alarmed or concerned about it and support a strong national response. Another 19 percent (cautious) believe it is a problem though they are not convinced that it is an urgent threat.

The disengaged respondents (12 percent) have not lost much sleep over the issue but could easily be persuaded otherwise. The remaining fraction—the doubtful and dismissive (18 percent)—fall somewhere between the Roger Pielke and Rush Limbaugh/Michael Steele camps.

Though these results may not appear notable in of themselves—after all, the majorities that believe global warming is a grave threat in other countries are much larger—they do reflect a significant shift in public opinion over a short period of time. Indeed, the previous version of the survey, which was released last December (and taken in the summer of 2007), found that only 41 percent of respondents were either alarmed or concerned by global warming (19 percent and 22 percent, respectively).

The percentages of respondents identified as cautious or unconcerned were almost identical (20 percent and 12 percent, respectively). On the other hand, the percentage of respondents that considered themselves doubtful or dismissive was appreciably higher (27 percent).

Given that efforts by the rightwing and their allies in industry to misinform the public have proceeded apace, if not accelerated, over the last year, that is a fairly sizeable change. It is also notable that all segments, except for the doubtful and dismissive, support an international treaty to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Similarly, a strong majority supports the regulation of carbon dioxide as a pollutant.

In light of all the attention lavished on global warming and green issues during the presidential election, these results are about in line with what I would’ve expected to see—and somewhat contrary to the findings of a leaked EcoAmerica report that suggested that the term “global warming” was not helping sell the message.

I’ve never been a fan of talking points and messaging, especially in the context of scientific issues like global warming and stem cell research, and have been skeptical of efforts by EcoAmerica and others—however well-meaning—to “rebrand” the term to make it more palatable to the mythical “Joe Sixpack.”

Any attempt to re-package the science, let alone the term, damages the credibility of the research community and risks politicizing an issue that should (ideally) know no ideology. I’ve always been of the mind that a majority of the American public is receptive to scientists’ message; it just needs to be phrased simply and effectively (which is easier said than done, of course).

In a recent online discussion hosted by SEED, Michael Mann and Gavin Schmidt of RealClimate made essentially the same point, arguing that scientists must use all available tools to communicate the facts of global warming to a lay audience—but they must always do so by “playing by the rules.” As Mann explains:

“Rather than engaging in the artifice of misrepresentation and cherry picking, we must find clever, simple ways to convey the facts. To do otherwise would constitute unilateral disarmament in this war.”

For his part, Schmidt pooh-poohs the notion that scientists need messaging strategies to convey the severity of global warming:

“Overly messaged phrases as suggested by EcoAmerica might be helpful for advocates of various policies since they are indeed trying to sell something. Only rarely does such a reframing stick, however. And when obviously framed language infects discussions of the science, it serves only to leave the impression that the scientists themselves are selling something, which should concern anyone who worries about the over-politicization of science. Carbon dioxide is the perfect description of the gas consisting of a molecule of carbon and two oxygen atoms; it doesn’t need to be burdened with an additional focus-group-approved label.”

While I am sympathetic to the views of some of the other participants, many of whom point out that framing and messaging, though often used ad nauseam, have been shown to work in many circumstances, I am one of those who believes that the science should be able to stand on its own merits.

Having worked with scientists for many years, I can honestly say that they are among the most skeptical individuals that I have ever met; any new theory or idea that is introduced, however inconsequential it may seem, is often subject to a barrage of criticism and doubt.

It can take several years, if not decades, before some ideas are accepted by a majority of scientists. As Elizabeth Kolbert notes in her latest piece for The New Yorker (sub. required), the idea that a six-mile-asteroid rammed into the Earth at the end of the Cretaceous (known as the Alvarez hypothesis), causing a mass extinction, was initially treated with disbelief and contempt.

It was only a decade or so later, after more evidence to support the hypothesis was discovered, that the idea moved into the mainstream. The reason that an overwhelming majority of scientists agrees on the basic tenets of global warming is that there are literally decades of research to back it up.

With a solid, though somewhat flawed, cap and trade bill set to pass the House, and a new administration that is solidly focused on the issue, I am optimistic that the consensus among the general public will only continue to strengthen. It will take time before the release of a study like MIT’s latest, which predicts a 10°F increase by 2095 and 866 ppm, causes the same degree of alarm in the public that it does in me, but it will eventually happen.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts