This post is a part of DeSmog’s investigative series: Cry Wolf.

Five years overdue in a legal sense and ten years after caribou were officially listed as ‘threatened’ according to the Species at Risk Act, the Canadian government has finally released its controversial Recovery Strategy for the Woodland Caribou. The report, originally released in draft form in August 2011, ignited severe public criticism for emphasizing ‘predator control’ options like a provincial-wide wolf cull in order to artificially support flagging caribou populations in Alberta.

The new and improved federal recovery strategy seems poised to remedy that, however, with dramatic improvements made to habitat protection and restoration legislation. Under the current strategy, the oil and gas industry, and the government of Alberta must work together to ensure

a minimum of 65 per cent of caribou habitat is left undisturbed for the species to survive.

At least 65 per cent of caribou habitat must be left undisturbed for caribou herds to have a 60 per cent chance of being self-sustaining. Government and industry must make immediate arrangements to remediate caribou ranges that currently do not meet that 65 per cent benchmark within the next five years.

In an interview with DeSmog,

Alberta Wilderness Association (

AWA) conservation specialist

Carolyn Campbell said without specific guidelines in place, provinces like Alberta are left to their own devices, which could include lengthy delays or piecemeal recovery options that have proven ineffective in the past. What decisions are made in the course of the next five years could mean the difference between survival and local extinction for some herds.

According to Campbell the current strategy, while improved, cannot be considered a success yet:

“Under strong pressure from the Canadian public, it appears the federal government has significantly improved the caribou strategy. There are much better goals of showing progress every 5 years towards a 65% undisturbed habitat target for even the most vulnerable herds. This is important for caribou in Alberta’s boreal forest, all except one of which are already in serious decline and expected to die out in the next several decades if nothing is done because of multiple pressures from oilsands, forestry and oil and gas development.

Instead of the draft strategy’s unacceptable preference for wolf kills, the good thing about this final strategy version is the most urgency is clearly given to landscape level planning and to habitat restoration.

Yes, it would be better if the plan’s target for populations to be self-sustaining was set at 80% probability rather than 60% probability. But given that so much of the Alberta population’s habitat is disturbed already, actually moving towards a 65% intact habitat would be significant – so for us the key issue is to call for swift implementation action, to get governments to set in motion on-the-ground actions to get us there.”

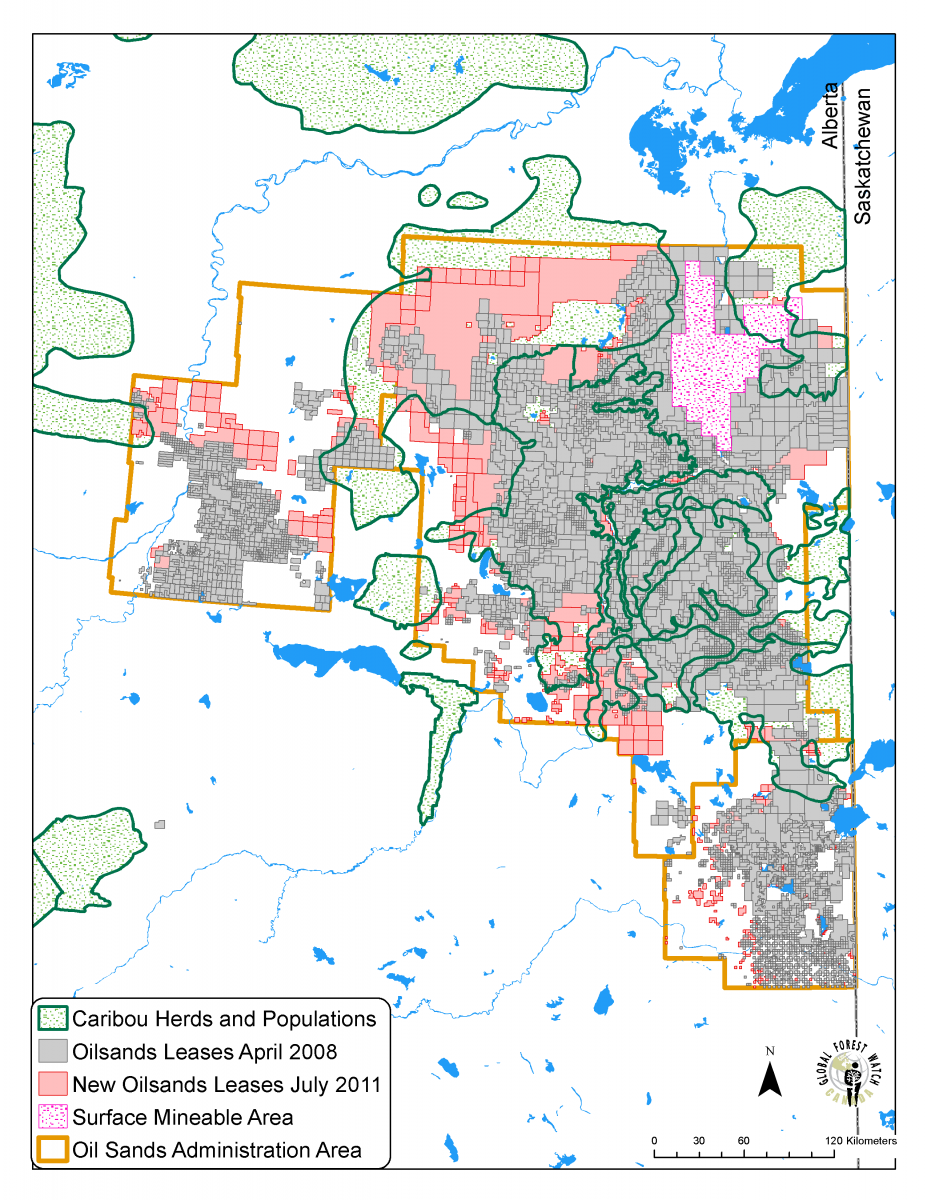

Company leases in the tar sands region currently blanket vast portions of critical caribou habitat, a concern some say the current federal strategy fails to adequately address.

For Campbell, the two outstanding concerns conservation groups like the AWA have with the current federal policy as it’s written are these:

1. Lengthy delays in implementing actions on the ground (range plans could take 3-5 years to develop, after which the federal government develops action plans). “The federal government,” says Campbell, “has set a terrible example this way in not meeting its mandatory timelines, and delay is deadly for caribou.”

2. Immediacy leading to faulty habitat management. “The provinces could interpret the urgency of ‘habitat management’ to mean relying on already failed project-by-project level operating practices – so the plan’s intent could fail if the provinces choose a certain (wrong) interpretation of the habitat management side,” Campbell said.

One Caribou, Two Caribou, Free Caribou, Zoo Caribou

One contentious option already on the table is the construction of

massive caribou pens, designed to act as a wildlife refuge for the struggling species. The idea of a caribou pen,

hatched in part by the Oil Sands Leadership Initiative, an industry group, is present in the federal caribou recovery strategy, mentioned as a possibility for “indirect predator management.”

According to the CBC the caribou enclosure would close off “at least 1,500 square kilometers to protect caribou from predators such as wolves.” The caribou “lifeboat” as some proponents are calling it would be put in place for 40 years and host between 120 to 150 caribou.

Stan Boutin, one of Alberta’s preeminent caribou experts and professor at the University of Alberta has recently

come out in support of the idea, noting the federal recovery strategy does not allow for the interruption of industrial activities if caribou habitat thresholds are not met. The result, for Boutin, is a strategy that allows industrial expansion to continue as long as a

“vague plan” is in the works. If that continues for another decade, it could have severe consequences for extremely weakened caribou herds.

Conservation biologist Ian Hugget

suggests that Boutin “bases his arguments on the assumption that society places greater emphasis on resource exploitation than on wildlife conservation.”

“Rather than…forcing wildlife to adjust to our ever-expanding industrial enterprise..we should take stock of our northern development’s profound impacts on existing species that call the landscape of northern Alberta home. Once biologists, advocates for the sanctity of the natural world, adopt a worldview that the rest of animate creation comes second to human exploitation, commerce and greed, we have failed our profession,”

Huggett wrote in an email to the CBC.

However, Boutin, is a realist – even if a jaded one – and for decades he has struggled to make a difference for caribou in Alberta. If anyone knows the difficulty of pleading with industry and government in an oil-rich place like Alberta on behalf of a threatened species, it’s Boutin.

In an interview with DeSmog in early 2012, Boutin said,

“the caribou are one indicator of what’s considered a failing of the environmental responsibility in the area. And I think that’s true. But I think the public on the other side has to be realistic.

Look, if we want to exploit this resource as a mine it’s like any mine – we create an enormous hole in the ground and there’s not going to be any biodiversity there. Environmentally its doing nothing for the environment on that local scale but we as a public have to decide what is acceptable in terms of environmental things. And it might be that clean water flowing in the Athabasca is an absolute – it must be maintained. But in the same sense we can’t expect the oil sands mines to have caribou on them – they’re not going to.

So we have to decide in a much more realistic fashion where we want that conservation to take place and where we want exploitation of the resource to take place and that’s a public decision. The balance is somewhere in this mix and right now many people perceive the balance is shifting far too much towards the actual exploitation of the energy resource.

I don’t know what the right answer is but the public needs to realize you can’t have this outstanding environment and an oil sands mine in the same region. So what should we demand as a public in this instance? I don’t think that dialogue has gone beyond the very trivial battle between caribou and oil sands for example. We’ve got to be much more sophisticated in those decisions it seems.”

At the time of the interview Boutin said the oil industry was considering caribou pens as a way to alleviate public scrutiny of oil extraction practices.

“That’s why they’re looking to those very radical solutions like large fenced areas which would be a way of keeping predators and deer and moose out of caribou ranges without wolf control. It’s a zoo, a huge zoo, a natural zoo. Very different from what people are currently thinking about. But this is something radical we may have to think about if we want to keep caribou where they are because other options might not work. I think we need to entertain these crazy sounding ideas to see if they hold water, not disregard them off hand,” he told DeSmog.

But Boutin’s call to creativity in the instance of caribou recovery is not guided by the principles of conservation that some might like to see at the helm of such recovery projects. Instead, Boutin is caught between a rock and a hard place, so to speak, where the status quo – of both government and industry – means the ensured local extinction of a species.

The fenced caribou sanctuary does not represent the best option, but perhaps the only option in a context dominated by oil extraction politics, where the vices of industry and the mantra of economy trump even the most telling symbols of a failing system: extinction.

Image Credit: Sean Clawson, licenced under Flickr Creative Commons.