This is a guest post by Anna Simonton, on assignment with Oil Change International.

Carolyn Marsh was in her living room watching television on a Wednesday night in August when she heard a loud boom from somewhere outside. Having lived in the industrial town of Whiting, Indiana––just south of Chicago––for nearly three decades, she wasn’t terribly shaken. “There’s a lot of noise constantly,” she explains.

But when the news came on an hour later and reported an explosion at the nearby BP refinery, Marsh was incensed. It was the second serious incident since the recent completion of BP’s Whiting Refinery Modernization Project, which Marsh had fought to prevent.

In December 2013, after six years of community pushback, court battles, Environmental Protection Agency citations, and ongoing construction in spite of it all, BP’s $4.2 billion retrofitted facility came fully online.

Part of the Whiting Refinery Modernization Project, this new coker creates a byproduct called pet coke that is burned for fuel like coal, but is much dirtier.

It was now a tar sands refinery, capable of refining 350,000 barrels of the world’s dirtiest oil per day. And it was paid for, in large part, by U.S. taxpayers.

A little-known tax break allows companies to write-off half of the cost of new equipment for refining tar sands and shale oil. According to a report by Oil Change International, this subsidy had a potential value to oil companies (and cost to taxpayers) of $610 million in 2013.

Tar sands are petroleum deposits made up of bitumen mixed in with sand, water and clay. Their production is extremely destructive at every stage: from strip mining indigenous lands in Canada, to disastrous accidents along transportation routes, to dangerous emission levels produced by refining the heavy crude, to the hazards imposed on communities saddled with tar sands byproducts like petroleum coke (“petcoke”), and finally to the greenhouse gases pumped into the atmosphere when the end product is used for fuel.

Despite all the reasons to keep tar sands in the ground, the refining equipment tax credit has helped put tar sands development in the U.S. on the rise, accelerating climate change at the expense––in every sense of the word––of American taxpayers.

Subsidizing the Dirtiest of Dirty Oil

Heavy speculation and investment in Canadian tar sands extraction have been going on since at least 1995, when the oil industry set a production target of 1 million barrels per day by 2020. That goal was reached far ahead of time, in 2004. Now the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers predicts a rate of 4.8 million barrels per day by 2030 if currently planned expansion holds.

In order to take full advantage of Canada’s tar sands-driven energy boom, American refineries would need to make costly retrofits to century-old facilities designed for the light crude that once flowed plentifully from domestic oil wells––not heavy tar sands crude with a consistency like molasses.

Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA) gave the oil industry a kick in that direction when he introduced a tar sands refinery equipment tax break to the Energy Policy Act of 2005, a bill that funneled $85 billion worth of subsidies to the energy sector.

A report by The Pew Charitable Trust estimated that, between 2005 and 2009, this refinery equipment tax break alone cost the government $1.2 billion and increased emissions by more than two million metric tons of carbon.

In the years since Grassley incentivized tar sands retrofits, refineries across the midwest have sprung into action, undertaking massive overhauls to accommodate the tar sands crude that already flows into the U.S. through the original Keystone pipeline and Enbridge’s sprawling network of pipelines.

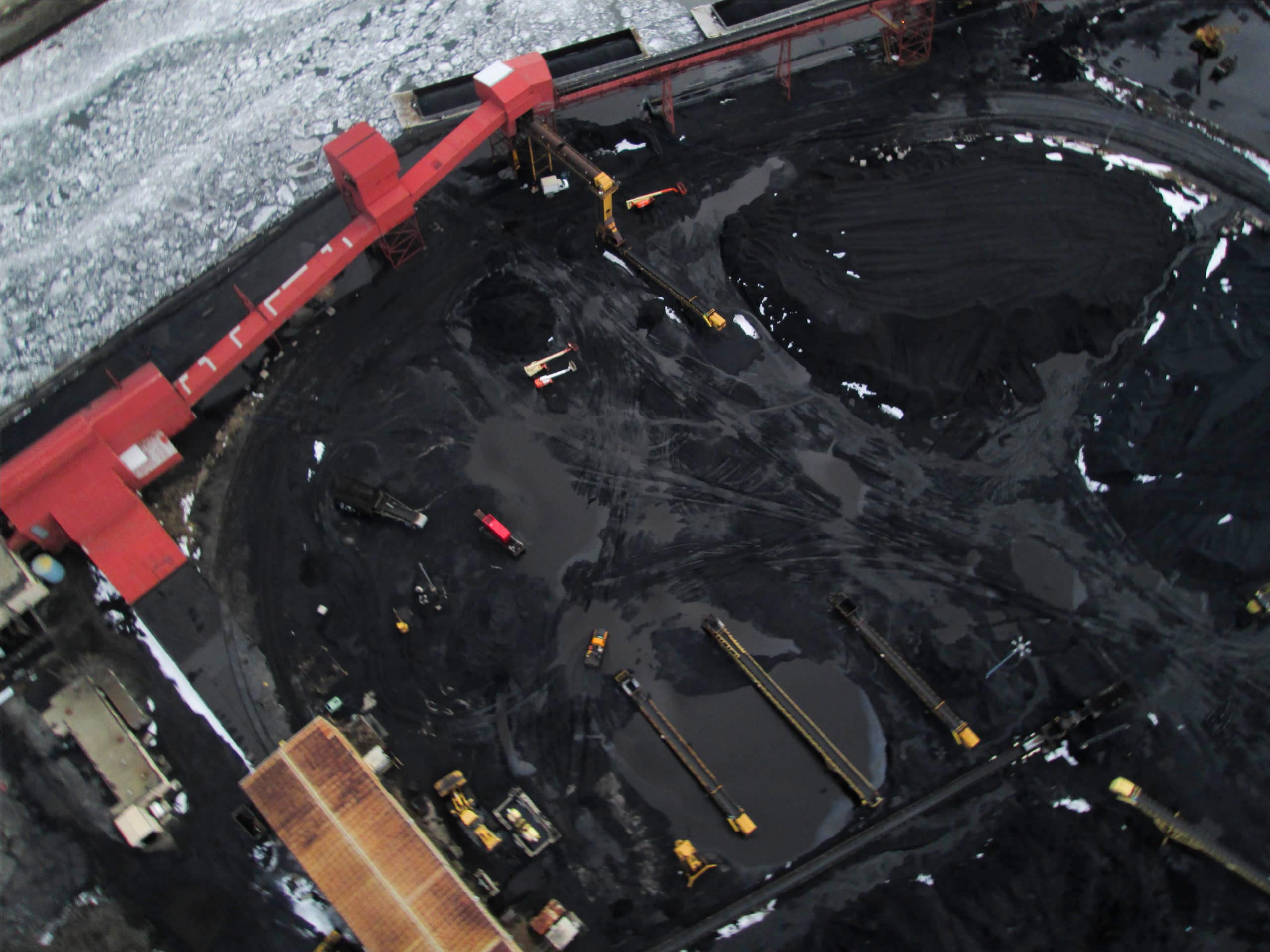

KCBX, a subsidiary of Koch industries, stores open piles of petcoke at it’s 90 acre terminal along the Calumet River in Chicago’s Southeast Side. (Credit Public Lab)

As a result, between 2010 and 2012, tar sands refining in the U.S. increased by 43 percent, according to Oil Change International. By 2012, tar sands accounted for 10.7 percent of the total crude oil processed in U.S. refineries.

State and municipal governments have jumped on the tar sands subsidy bandwagon as well, offering tax breaks and other incentives to refineries considering tar sands retrofits.

One of the biggest handouts came, astonishingly, from the cash-strapped city of Detroit, whose city council approved a whopping $175 million tax break to Marathon for a tar sands upgrade in 2007. Earlier this year, city council members expressed dismay that the massive subsidy created only 15 new jobs for Detroit workers.

“In a city with double-digit unemployment, any company that’s receiving a tax abatement of nearly $180 million should be giving more back, including hiring residents,” Councilwoman Saunteel Jenkins told the Detroit Free Press.

“They’re dangling carrots in front of minorities in the city of Detroit,” a worker rejected by Marathon told the Detroit Free Press. “They feel like they can do that. It’s a renegade refinery running over poor people.”

BP’s Whiting Refinery Modernization Project got a significant boost from local coffers as well. In 2008, Indiana’s state development agency awarded BP a $400,000 tax break in a deal that required the company to train 1,583 Indiana employees and hire 74 new ones by 2013. Strangely, in 2012, the same agency gave BP an additional $1.2 million with the same stipulation of hiring 74 people by 2013, but without the training.

This cozy relationship between BP and Indiana’s government was solidified several years earlier, before the Whiting Refinery Modernization Project was ever on the table. In 2003, BP successfully pushed for a tax reform law that shifted the company’s tax burden directly onto Indiana residents and paved the way for the refinery expansion.

Refinery Expansions on the Backs of Taxpayers

Carolyn Marsh remembers the shock when her property taxes tripled. “I had been paying less than $1,000––my house is 105 years old––and suddenly I owed almost $3,000.”

Carolyn Marsh spots sparrows in a bird sanctuary on the outskirts of Whiting Indiana, where a BP refinery now processes tar sands. (Credit Anna Simonton)

Born and raised in Chicago, Marsh moved to Whiting in 1987 when her fifteen year career as a steel mill worker came to a grinding halt during one of the final chapters of rust belt de-industrialization.

With no children, a frugal lifestyle, and union wages, Marsh had saved quite a bit, though not enough to live in one of the Windy City’s lakefront neighborhoods. She was an avid birdwatcher, and living within walking distance of Lake Michigan, where migratory birds and waterfowl commingle, was Marsh’s dream.

Whiting, just 17 miles south of downtown Chicago, had parks along the lake and a wilderness area that Marsh would later save from development by pressuring city leaders to designate it as a bird sanctuary. Because it was an industrial area, property taxes were low, and the older homes were affordable.

But Marsh says it was a trade off. “If I wanted to live cheaply and have a house, I would have to tolerate living near a refinery,” she explains. “It’s dangerous. Refineries leak all the time and this whole area has a huge asthma problem.”

For 16 years, Marsh lived with that trade off, until BP threatened to seek out lower property taxes elsewhere and state lawmakerskowtowed to the corporation’s demands. The resulting legislation cut industrial property taxes by 14 percent, shifting hundreds of millions of dollars of taxes onto residential property owners like Marsh.

“Living cheap is no longer the situation for me or for others,” Marsh says. “But we still live with the pollution and the results of accidents at the plant.”

When the company announced its plans to refine tar sands in 2006, a BP executive credited the 2003 tax reform, saying the expansion would have been “much less likely,” under the old tax structure.

Marsh was instrumental in challenging the modernization project, testifying in a lawsuit concerning BP’s air permit. A 2012 settlementforced the company to pay an $8 million fine and spend an additional $400 million dollars on technology to reduce pollution.

Marsh was also involved in the public outcry against BP’s water permit, which originally allowed the refinery to discharge 54 percent more ammonia and 35 percent more industrial waste into Lake Michigan.

But, in Marsh’s view, these hard-won mitigations have had a minimal impact.

Only three months after BP’s Whiting Refinery Modernization Project was complete, the facility spilled what BP estimated to be between 15 and 39 barrels of oil, very likely the heavy tar sands crude, into Lake Michigan, a source of drinking water for millions of people. Five months after that, the explosion Marsh heard caused a fire inside the refinery. It was quelled by the end of the night, with one reported injury, according to BP.

“They should shut the damn thing down,” Marsh says. “We can’t keep exploiting our natural resources to put gas in our cars. It’s insane.”

Investing in Politicians to Protect Their Profits

Accidents like these are run of the mill for BP. With annual profits in the tens of billions of dollars, the corporation has a long history of opting to pay big fines rather than clean up its act.

The company also uses its war chest to exert influence over policymakers. According to The Center for Responsive Politics, BP has spent $95 million lobbying Congress since 1998. Individuals and PACs affiliated with BP have contributed a total of $7 million to Congressional election campaigns.

When the Energy Policy Act made its way through Congress in 2005, BP threw down $1.6 million to lobby for a number of provisions, including, ““issues with expanding refining capacity” according to their lobbying disclosure.

Though BP’s SEC filings don’t specify which tax credits the company has taken advantage of, its 2013 annual report does say that BP not only had $200 million in U.S. tax benefits that year, it also had $1.7 billion in U.S. tax credits stored up.

Corporations are allowed to carry over tax credits from one year to the next in order to use them at the most opportune time––generally those years when profits are high.

A footnote in the filing further explains that BP accumulated the $1.7 billion in tax credits between 2005 and 2011, which is both within the time window of eligibility for the refining equipment tax credit and within the time that construction at the Whiting refinery was underway.

All in all, it seems that BP got a big bang for its buck, spending $1.6 million to push through a plethora of self-serving provisions and likely writing off huge chunks of its $4.2 billion refinery upgrade as a result.

But they were hardly the only ones. On the long list of corporations that poured lobbying money into the Energy Policy Act of 2005, the infamous Koch Industries stands out. They too had something to gain in pushing for the refinery equipment tax break, which was among the many provisions they spent nearly $1.58 million lobbying for.

Mounting Toxic Byproducts

Olga Bautista has lead the fight to ban petcoke storage in Southeast Side, Chicago. Now she’s running for 10th Ward Alderman. (Credit Anna Simonton)

When the 30-foot-tall black mounds appeared along the Calumet River in Southeast Chicago in early 2013, Olga Bautista thought the ominous forms were piles of coal. She grew up in the industrial area and was used to coal trains passing through on their way to the power plant in Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood.

In the coming months, Bautista’s husband would pressure wash a sticky black film off their home multiple times. Her young daughter would come in from playing in the backyard, her face smudged with a sooty-looking substance that didn’t wash off easily.

Shortly after Bautista gave birth to her second daughter, a friend visited, bringing news from a meeting of the Southeast Environmental Task Force, where both women volunteered. The huge mounds were something called petcoke, the friend told Bautista.

“We started to make the connection,” she says.

They learned that petcoke, or petroleum coke, is a byproduct of oil refining that looks and burns like coal, but is much dirtier, emitting5-10 percent more carbon dioxide per unit of energy. Refining tar sands bitumen requires a process called coking that produces far more petcoke than conventional oil refining.

Thus, as the Whiting Refinery Modernization Project gradually came online, petcoke began piling up on the banks of the Calumet River, awaiting shipment to countries where emissions standards are lower. The middleman? KCBX, a subsidiary of Koch Industries.

Piles of petcoke at the East 100th Street entrance to the KCBX terminal. (Credit Anna Simonton)

Bautista describes the population of Southeast Chicago as working class. “We are teachers, nurses, police officers, firemen. We are in the service industry, cleaning hotels, working at Wal Mart and Dollar Stores. We are the backbone of this city.”

Yet, the neighborhoods that make up Southeast Chicago are some of the most underserved, particularly South Deering, one of the areas nearest to the petcoke piles.

“It’s a transit desert, it’s a food desert,” Bautista says. “They had one laundromat that has recently burned down. People are washing their clothes in their bathtubs.”

Southeast Chicago is predominantly Latino. As the city’s industrial corridor, it’s long borne the brunt of environmental racism. The Southeast Side has higher rates of asthma, heart disease, stroke, and cancer than the Chicago area as a whole.

After years of living with pollution, Bautista says, many residents were initially unfazed by the petcoke piles. But then a particularly windy day in August, 2013 catalyzed the community into action.

Hulking hills of pet coke loom behind this baseball field, where a little league game was cancelled last year after strong winds covered players and their families in pet coke dust.

“People were calling 911 because they thought the neighborhood was on fire,” Bautista says, describing the thick cloud of petcoke dust that whipped through Southeast Chicago that day, blanketing homes and sending dozens of people to clinics with respiratory issues.

After that, a number of community groups formed Southeast Side Coalition to Ban Petcoke and began a campaign to pressure city government to force out KCBX and it’s waste piles.

Petcoke covers the railroad tracks that are a border between the backyards of Southeast Side, Chicago families and KCBX’s terminal. (Credit Anna Simonton)

They’ve packed public meetings, taken elected officials on petcoke tours, and marched through the streets of Southeast Chicago, 200 strong.

Last March, Mayor Rahm Emanuel issued regulations that ban new petcoke facilities and require KCBX terminals to fully enclose its petcoke piles by 2016.

KCBX says they need at least four years to accomplish this––and they’vethreatened to sue to get their way. They’re also demanding permission to pile the petcoke fifteen feet higher.

Meanwhile Illinois’ Attorney General has filed suits against KCBX for pollution violations, and in June the US EPA found KCBX to be in violation of the Clean Air Act.

While these moves constitute some modest progress, a Chicago city webpage about petcoke casts doubt on how seriously elected officials are treating the issue. The patronizing Q and A actually instructs residents to just stay inside and clean their homes in order to avoid exposure to petcoke dust.

“This is the kind of violence we’re under,” Bautista says. “We’re risking our lives just by breathing the air while these corporations are using tax loopholes to abuse us and make a profit. We’re financing our own misery.”

Fighting Petcoke, Fighting for Climate Justice

A view of the Koch brothers’ petcoke piles from the property line of a resident in the Slag Valley neighborhood of Southeast Side Chicago. (Credit Anna Simonton)

Recently, KCBX’s petcoke piles have shrunk. But members of the Southeast Coalition to Ban Petcoke discovered they’ve been moved onto barges anchored at points in the river not visible from public property.

Bautista suspects that this is a tactic to minimize the issue of the petcoke piles in the upcoming elections. It’s unlikely to work, since she’s running for Alderman.

Her platform isn’t only about opposition to KCBX storing petcoke, though. Bautista is part of a growing movement for climate justice that demands broader systemic change from corporations and governments. In September she spoke in the closing plenary of the NYC Climate Convergence, held in conjunction with the historic People’s Climate March.

Her speech connected the struggles of people in Whiting, Southeast Chicago, Detroit, and so many other communities suffering the consequences of massive corporate welfare for the fossil fuel industry.

“BP and Koch industries are polluting our community, and it’s time they and companies like theirs pay up big time or get out,” she told her audience.

“This is what is meant by class warfare, but it’s only war when we rise up and fight against the forces that have hijacked our lives…Win or lose there is something about living a life with dignity––with our heads held high and exposing these systems that tear us down everyday while only a small minority profits in any way…Our backs are already against the wall. The only way to move is forward.”

TAKE ACTION: You can help put an end to fossil fuel subsidies and extreme energy extraction by clicking here.

This story was written by Anna Simonton, on assignment with Oil Change International. It’s the fourth in a series of “subsidy spotlights”, highlighting the real-word impacts of fossil fuel subsidies. You can read our first subsidy spotlight here, our second here, and our third here.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts