By Rhiannon Fionn

Until the Tennessee Valley Authority’s coal ash disaster shoved homes from their foundations in the middle of the night in Dec. 2008, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, bending to pressure from industry, allowed coal plants to self monitor coal ash waste. But once the glare of the national spotlight called that conflict into question, newly appointed EPA Administrator Lisa P. Jackson vowed to put a coal ash regulation in place by the end of 2009.

Nearly seven years after the spill in Kingston, Tenn., that long-awaited regulation becomes effective today, Oct. 19.

While the EPA’s coal ash regulation seems like a major step forward in protecting America’s environmental health and drinking water, the truth is that it’s more of a preferred practice than a law. That’s because it is ultimately up to citizen lawsuits, usually via environmental organizations, to make states enforce the law.

Nearly half a million people commented during the agency’s eight city public meeting tour in 2010, though it took another four and a half years and dilution from the White House before the regulation was finalized, and an additional four months before it was published in the Federal Register. It’s taken yet another six months to get us to this point.

For decades, EPA debated over whether or not to regulate coal ash waste at all.

Today, with a regulation finally in place, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the debate has ended. It has not.

As recently as this past July, the U.S. House of Representatives passed legislation that could prevent EPA from doing its job — its sixth such attempt – none of which have made it to the president’s desk. Even though these attempts proved futile, it’s the White House Office of Management and Budget that is credited with both stalling the regulation and making EPA back off its “hazardous waste” label.

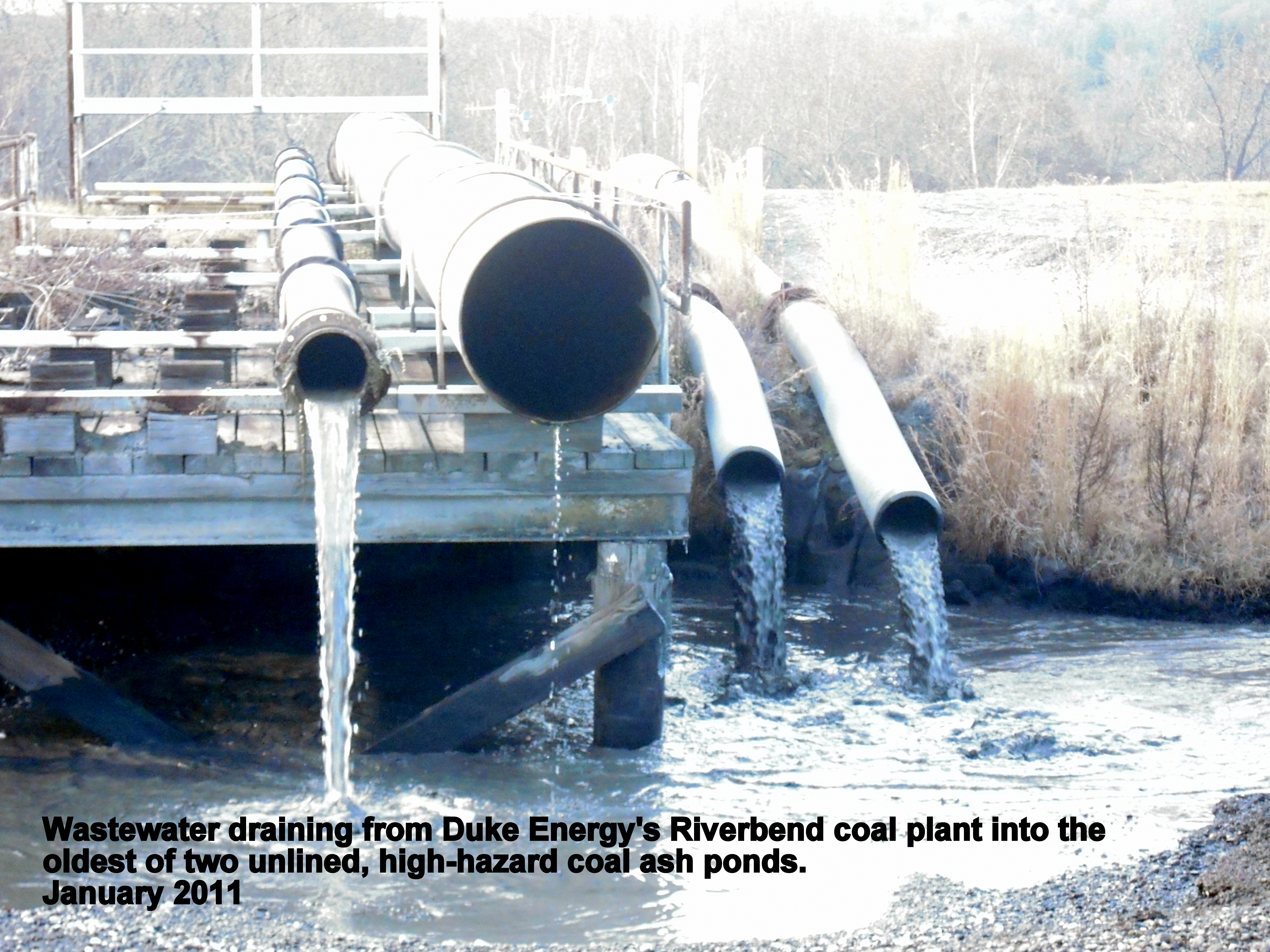

Ahead of its effective date, the regulation has led several states to announce plans to close ash impoundments, or “ponds” full of this concentrated industrial waste. But “closure” is a far cry from a “cleanup,” which matters since the ash pits not only legally drain into waterways across the nation, but they’re also known to illegally leak and seep into public drinking water reservoirs. Groundwater monitoring data indicate that where there is a coal ash waste pit there is very likely groundwater contamination.

“Today, the largest source of toxic water pollution in this country is coal ash,” Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., president of the Waterkeeper Alliance, told me. “In fact it contributes more toxic pollution than all nine of the next big emitters combined,” he added.

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., president of the Waterkeeper Alliance, standing in the woods near Mountain Island Lake and Duke Energy’s Riverbend coal plant, which has two unlined, high-hazard coal ash ponds. Photo by Kevin J. Beaty for Coal Ash Chronicles.

EPA acknowledges that “coal ash contains contaminants like mercury, cadmium and arsenic associated with cancer and various other serious health effects.” And in 2010, the agency estimated that the public could realize $290 billion in health care savings annually if the waste were regulated – an estimate has since vanished from the agency’s website.

Contrast that with EPA’s estimate that a cleanup will cost the coal industry $8.1 billion. And consider this: jobs will be created in the process. During the long fight over the regulation following the TVA disaster, industry claimed such regulation would cause the loss of 300,000 jobs.

In 2011, Frank Ackerman of Tufts University’s Stockholm Environment Institute published a white paper describing that number as “simply unbelievable” and the result of either “unreported assumptions or from errors in calculation.” The conclusion of the paper is that an estimated 28,000 jobs will be created as coal ash is cleaned up.

During the public comment period for the coal ash rule, environmentalists and citizens made it clear that they want coal ash labeled as “hazardous waste.”

They didn’t win that label, but they did get some protections: The Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals from Electric Utilities (DCCR) rule calls for the closure of all ash waste pits that fail to meet structural standards, additional groundwater monitoring, the cleanup of unlined ponds that contaminate groundwater, liners for new ponds and restrictions on where they’re located.

The DCCR rule also encourages the “beneficial reuse” of coal ash as an ingredient in other products, including concrete – something industry claimed to want while repeatedly stating that regulation would “stigmatize” its business, a claim that’s also been debunked.

Still, the fight continues. Look no further for evidence than last month’s paltry settlement between the state of North Carolina and Duke Energy, the world’s largest energy producer – a settlement that’s now being challenged in state court by the Southern Environmental Law Center.

“In settling this fine, the (N.C. Department of Environmental Quality) has agreed to abandon its enforcement of groundwater laws at all 14 Duke Energy coal ash storage sites in North Carolina, to give Duke Energy amnesty for existing and future groundwater claims at all sites, to settle groundwater claims in existing enforcement actions, and to limit DEQ’s ability to monitor for groundwater contamination at all sites,” said Frank Holleman, a SELC attorney.

Rhiannon Fionn is an independent investigative journalist and filmmaker in post-production on the documentary film “Coal Ash Chronicles.” She is based in Charlotte, N.C.

Image by Ashley Phykitt

Blog image by United Mountain Defense.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts