On September 20, Duke Energy announced a $300,000 investment to install solar panel systems at up to 10 North Carolina schools. Numerous media outlets summarized Duke’s press release, hailing the company for its charity to schools and solar education.

A footnote in the announcement is key: Duke is doing this as part of a $5.4 million settlement in 2015 with the Environmental Protection Agency and several environmental groups over possible Clean Air Act violations.

The company denied any wrongdoing but settled “solely to avoid the costs and uncertainties of continued litigation.”

Duke’s press release and much of its coverage failed to disclose two important details: Duke is heavily involved with the two nonprofits in charge of the solar schools project, and the company has been actively restricting the solar industry in North Carolina for years.

Solar Schools and Pollution Penalties

The $300,000 solar investment is part of the settlement requiring Duke to spend “up to $600,000 for clean energy and energy efficiency projects in economically distressed counties in North Carolina and South Carolina.” Their settlement also includes a $975,000 civil penalty to the U.S. government.

Part of Duke’s investment will fund solar curricula and a related one-day teacher training, according to NC GreenPower, the nonprofit that will administer the grants.

“The cost savings to the schools is rather modest,” said Randy Wheeless, communications manager at Duke Energy, “but the opportunity to showcase the technology to students should pay nice benefits.”

But Caroline Hansley, a field organizer with Greenpeace USA, says, “Duke Energy’s solar schools program is a flashy way to dress up a penalty for pollution.”

Duke’s Green Nonprofits

Duke will invest the $300,000 through Raleigh-based NC GreenPower, which has a stated mission of “supporting renewable energy, carbon offset projects and providing grants for solar installations at K-12 schools.” NC GreenPower was established in 2003 by another nonprofit, Advanced Energy, which still “administers” the group. Both groups have Duke executives sitting on their boards of directors, but Duke omits this information from its announcements.

The energy titan, focused primarily on fossil fuel power generation, has the potential for considerable influence over the two nonprofits that are administering some of its green energy programs and that appear to inflate Duke’s commitment to renewables.

NC GreenPower has a board chosen by the North Carolina Utilities Commission, over which Duke has had influence as well. This board currently includes Robert Caldwell, vice president of efficiency and innovative technology at Duke, along with executives from other utilities, environmentalists, and academics.

Advanced Energy, also a Raleigh-based 501(c)(3) nonprofit, was founded in 1980 by the Utilities Commission “to investigate and implement new technologies for distributed generation, load management, conservation and energy efficiency.”

Its board president, Tony Almeida, was vice president at Duke Energy for 32 years and pushed for offshore drilling while an adviser to Republican Gov. Pat McCrory, who worked for Duke for 29 years.

Other board members have Duke ties as well and include Caldwell; Kendal Bowman, vice president of regulatory affairs and policy at Duke; Henry Campen, Jr., a partner and energy team leader at Parker, Poe Adams, and Bernstein, a law firm that often represents Duke

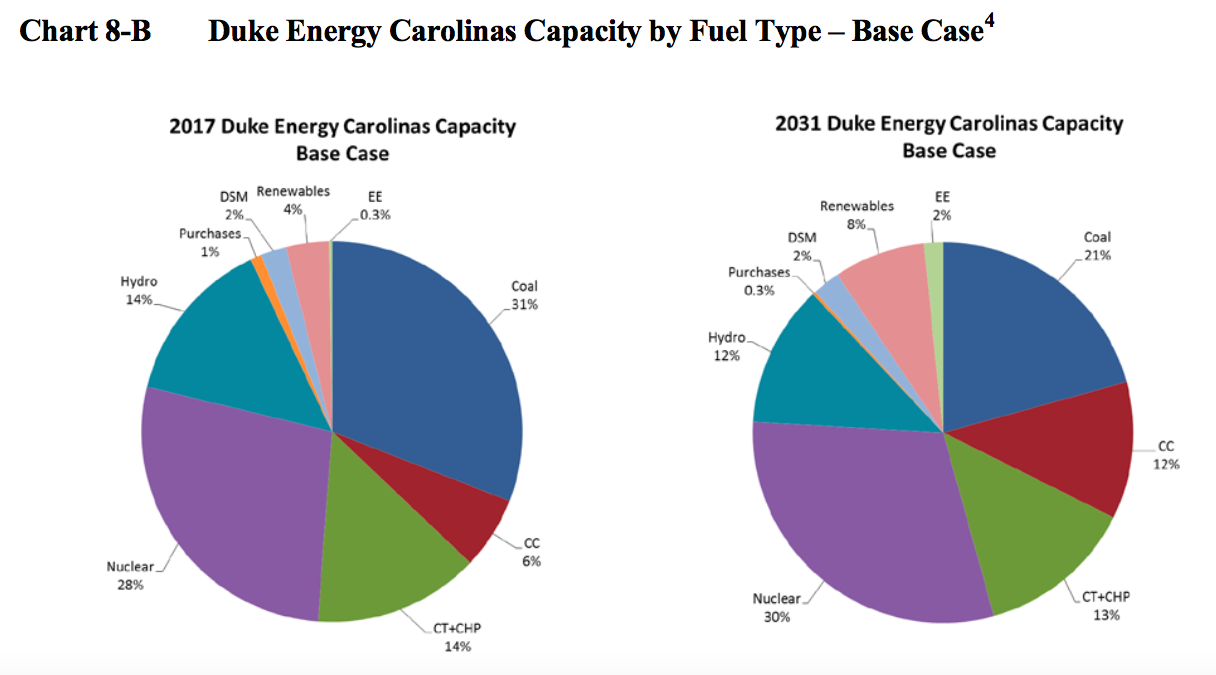

Ironically, what Duke is providing for several lucky schools is standard procedure in states that allow third-party solar agreements. These agreements allow non-utilities to install solar capacity for individuals, nonprofits, schools, and businesses at little or no cost and sell the electricity generated back to the customers at a much lower rate than the retail rate that utilities charge. North Carolina, however, is one of only nine states that either expressly forbids third-party solar sales or disallows them via other legal barriers, according to the NC Clean Energy Technology Center at North Carolina State University. “No-money-down solar options should be available for all schools in the state—not just the select few who qualify for Duke Energy’s program,” said Hansley. The new Duke grants are modeled after the existing “solar schools” program, launched last year, in which any K-12 school in North Carolina can apply for a 50 percent matching grant to install solar arrays. But in many other states, schools can have third parties install panels for free. A similar matching grant program would likely cost schools more money than a third-party arrangement. Duke Energy, which claims to be “one of the nation’s leading developers of renewable energy,” lauds North Carolina for being third in the nation in installed solar capacity, but it leaves out the fact that nearly all renewable energy comes from state public utilities. From August 2015 through July 2016, 97 percent of solar capacity in North Carolina came from public utilities, an increase from the previous year. This is because of the state’s ban on third-party solar sales and the fact that state legislators let North Carolina’s popular solar tax credit expire, with no objection from Duke, which remained publicly neutral. Thus, for most individuals, businesses, nonprofits, and places of worship, installing rooftop solar panels is cost-prohibitive. Scared that distributed solar would hurt its bottom line, Duke opposed the Energy Freedom Act, a 2015 bipartisan state bill that would legalize third-party sales of solar energy. Duke, the largest utility in the nation, benefits from restricting rooftop solar for three reasons: It can justify building more power plants, which it can fund by increasing consumers’ rates and which guarantee the company a 10 percent rate of return in North Carolina; customers will buy more energy from the electricity grid, operated by Duke; and Duke won’t have to pay many solar customers for their surplus energy that returns to the grid at the retail price, a process called net metering. The schools receiving free solar arrays under the solar program will be able to use net metering, but “the installations will handle a small portion of the school’s [overall energy] load, so this really shouldn’t come up much,” said Wheeless. Aside from holding back third-party solar, Duke plans to rapidly expand its natural gas operation and recently merged with Piedmont Natural Gas. Duke wants to construct up to 15 new natural gas plants in North and South Carolina alone. Methane, which leaks into the air during natural gas extraction and distribution, is a far more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. Duke projects that electric generation from natural gas will increase 36 percent for North and South Carolina by 2031. Despite the company claiming that it’s heavily invested in solar, renewable energy in the two states will account for just four percent of its total capacity in 2017 and eight percent in 2031, according to Duke Energy Carolinas’ 2016 Integrated Resource Plan. Image: Duke Energy’s projected power breakdown in the Carolinas by fuel type in 2017 and 2031. CHP (combined heat and power), CT (combustion turbine), and CC (combined cycle) account for natural gas generation. Credit: Duke Energy Additionally, in Florida, where Duke also operates, the utility has poured over $5.7 million into a deceptive ballot campaign that purports to protect consumers but in reality is designed to make sure third-party solar remains illegal and to lay the groundwork for eliminating net metering, which would hobble non-utility solar operations. A few weeks from the election, the initiative is polling well. Main image: Duke Energy Renewables’ Stanton Solar Farm in Orange County, Florida, where the utility has also been fighting distributed solar. Credit: Duke Energy, CC BY–NC–ND 2.0Clamping Down on Distributed Solar

Less-Than-Sunny Intentions

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts