Over and over again, attendees of the 2016 Energy by Rail Conference heard that “LNG by rail is ready to go!”

LNG, or liquefied natural gas, is methane that has been cooled to the point of being a liquid. So, how do we know that shipping this hazardous flammable material on America’s aging rail infrastructure is “ready to go”?

When trains carrying Bakken oil started derailing and exploding, there was a lot of head scratching about how this could happen since “crude oil doesn’t explode like that.” But a lack of research beforehand resulted in industry loading up unsafe rail cars with highly volatile oil in unit trains of 100 tank cars or more, stacking up the risk factors and increasing the likelihood of the accidents that followed.

With that knowledge in hand, will the burgeoning LNG-by-rail industry receive more scrutiny prior to being approved?

Not if the industry has anything to say about it. And it does.

Robert Fronczak, Assistant Vice President, Environment & Hazmat at the Association of American Railroads, a railroad industry group, explained the industry position to conference attendees in October.

While the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) is researching the risks of LNG by rail, according to Fronczak, “That could take several years to do and we don’t think it’s necessary to wait all that long … We think they should allow it immediately.”

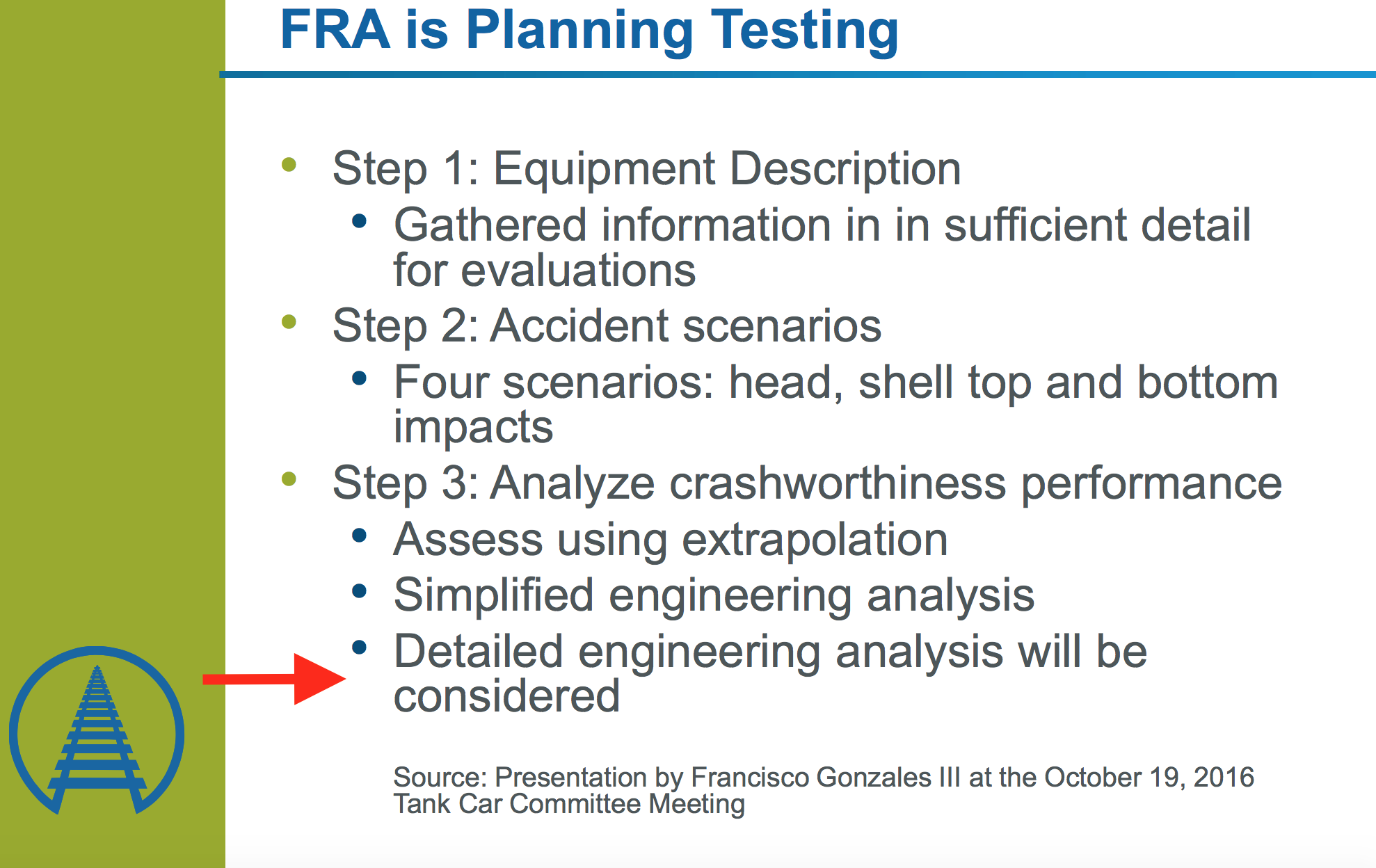

Fronczak included a slide in his presentation with a summary of the planned FRA research that he doesn’t think is worth the wait before proceeding with launching LNG by rail.

And he may have a point.

It appears the FRA is planning only a “simplified engineering analysis” of shipping LNG by rail, with a “detailed engineering analysis” merely something being “considered.”

Launching a whole new industry of hazmat transport by rail without a detailed engineering analysis — what could possibly go wrong?

DeSmog asked the Federal Railroad Administration about the planned testing, but the response provided few details:

“The testing is still ongoing … there’s no prediction yet on a completion date.”

And when asked whether transporting LNG-by-rail could receive approval before the the FRA had done things like “analyze crashworthiness performance,” the answer was, “There is no determination yet.”

While federal regulators may not have a clear vision for moving forward, Fronczak of the Association of American Railroads had no problem delving into the details. Fronczak explained precisely what the industry wanted from federal regulators, starting with approval for LNG to be moved in large tank cars like Bakken oil is, with a weight limit of 286,000 pounds.

Additionally, the industry group will petition for the allowance of LNG unit trains. Unit trains are those that would only carry one type of cargo, in this case, LNG, and would have no regulation regarding train length, or the number of cars on a single train.

Other than LNG requiring a different type of tank car than Bakken oil (in order to keep the natural gas cooled to liquid form), this would essentially push the limits on several risk factors, such as train weight and train length, which may increase the rates of derailment.

Fracked Gas Surplus Needs To Go Somewhere

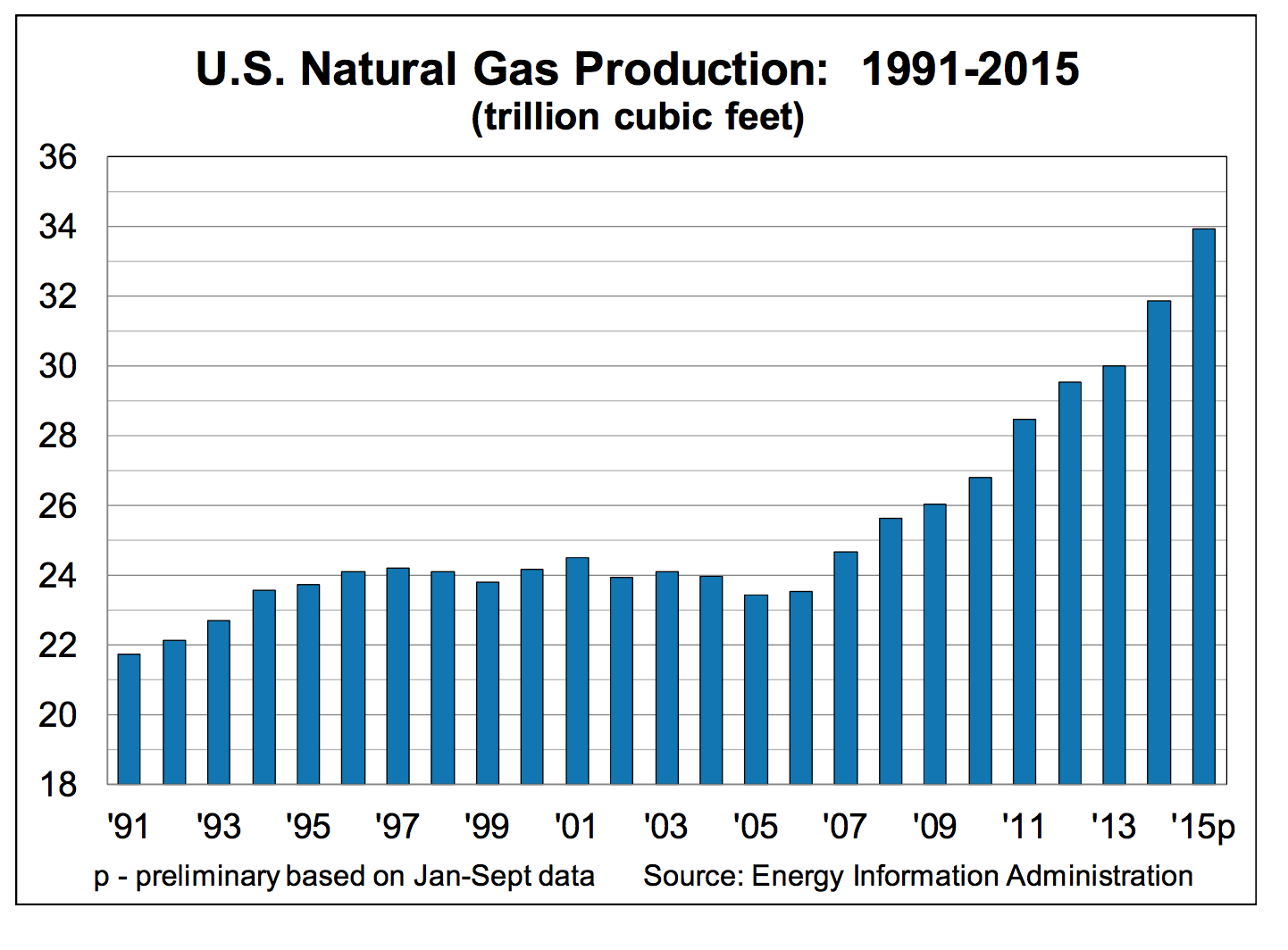

Just as the fracked oil revolution in the Bakken Formation led to the meteoric rise of oil trains, fracking is at the heart of the issue with LNG-by-rail as well.

The fracking boom brought us the dangers of explosive oil trains when Bakken oil production overwhelmed pipeline capacity and required producers to either cut production or put the highly volatile oil in the unsafe rail tank cars that were available at the time. There were no regulations regarding the length of these trains, which meant they were much longer than the average freight trains. Longer trains make more money for the railroads.

And the same thing is happening with fracked gas as it takes liquid form.

There is too much LNG and too many places the industry wants to move it to for pipelines to handle the current supply of LNG. As a result, the rail industry and tank car manufacturers are asking federal regulators to allow LNG transportation by rail — as soon as possible.

“LNG Doesn’t Explode”

At the Energy by Rail Conference, Robert Fronczac was followed on the LNG-by-rail panel by Scott Nason, a product manager for the rail products group at Chart Industries — makers of pretty much anything that has to do with LNG processing and storage, including rail tank cars.

Nason, whose employer is heavily invested in the success of LNG transport by rail, not only assured the audience that LNG by rail was ready to go but also made the claims that “LNG doesn’t explode” and that a train carrying the product “is not a bomb on wheels.”

Technically the first statement is true. Liquid natural gas does not explode. Just like liquid gasoline does not explode. Or liquid Bakken oil.

But when an LNG storage container is compromised, and the liquid leaves cryogenic storage and hits the atmosphere, is does not remain a liquid. And there is no doubt that at the right concentration with atmospheric conditions, natural gas — in vapor form — will explode when ignited.

Then, Nason is making a similar argument to the one the oil industry has made in the past about Bakken oil. If the trains stay on the tracks and the oil stays in the tank cars — there is no risk of explosion.

However, when there is a derailment and a tank car is punctured, there is considerable risk.

In 2014 there was an explosion at an LNG facility in Washington state. Risks of a second larger explosion resulted in authorities evacuating everyone within a two mile radius. Reuters reported, “A county fire department spokesman said authorities were concerned a second blast could level a 0.75 mile ‘lethal zone’ around the plant.”

The Sightline Institute reported on the explosion two years later with an article titled, “How Industry and Regulators Kept Public in the Dark After 2014 Explosion in Washington,” which detailed slow and incomplete reporting on the accident.

A 2009 report by the U.S. Congressional Research Service warned that LNG spills can unleash explosive vapor clouds. A 2004 blast at an Algerian LNG facility killed 27 workers and injured many more.

Lethal zones, a public kept in the dark, explosive vapor clouds, deadly explosions: LNG‘s history to date seems to call for careful and cautious oversight, yet federal regulators are only planning a simplified engineering analysis of LNG rail transport.

After Bakken oil trains started derailing and blowing up with an uncomfortable frequency, the head of the National Transportation Safety Board asked a simple question:

“How did it get missed for the last ten years?”

Will we be asking the same question about LNG by rail in the future?

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts