REEVES COUNTY, TEXAS — Travelers crossing the long stretch of arid desert spanning West Texas might stumble across an extraordinarily improbable sight — a tiny teeming wetlands, a sliver of marsh that seems like it should sit by the ocean but actually lays over 450 miles from the nearest coast.

This cienega, or desert-wetlands (an ecosystem so unusual that its name sounds like a contradiction), lies instead near a massive swimming pool and lake, all fed by clusters of freshwater springs that include the deepest underwater cave ever discovered in the U.S., stretching far under the desert’s dry sands.

Famous as “the oasis of West Texas,” Balmorhea State Park now hosts over 150,000 visitors a year, drawn by the chance to swim in the cool waters of the park’s crystal-blue pool, which is fed by up to 28 million gallons of water a day flowing from the San Solomon springs. The pool’s steady 72 to 76 degree Fahrenheit temperatures make the waters temptingly cool in the hot Texas summer and surprisingly warm in the winter, locals say — part of the reason it’s been called “the crown jewel of the desert.”

This remote locale also boasts some of America’s darkest night skies, allowing scientists and tourists alike to peer at far-off galaxies and to closely examine distant parts of the universe through the powerful telescopes at the nearby McDonald Observatory.

Iconic Texas wildlife — diamondback rattlesnakes, road-runners, and javelina — stir in the underbrush. And they’re not alone. Unique animals, including multiple endangered species, have adapted specifically to live in or near these springs’ desert waters, which in recent years have not only kept tourism thriving but also irrigated fields of crops and provided drinking water for the roughly 500 residents of Balmorhea, Reeves County, Texas.

The wild desert surrounding the springs here looks virtually nothing like it does further east, in the Permian Basin, where the oil industry has been in the midst of the nation’s biggest shale drilling frenzy.

Drivers on the interstate can smell oil in the air before they even see the oilfields outside Midland, Texas. From the mesquite and cactus-dotted plains atop the Permian Basin, over 2 million barrels of oil a day are pumped out of the ground. Dense fields of thousands of oil pump-jacks line roadsides, extracting fossil fuel from wells that are sometimes less than a football field apart.

Permian Basin pump jacks line desert highways east of Balmorhea. Photo Credit: Laura Evangelisto, © 2016.

But attempts to drill for oil here by the oasis at the foot of the Davis mountain range usually turned up dry holes. Until now.

In September, Apache Corp. announced a major new oil and gas find in Reeves County, a claimed $80 billion discovery that could turn the region’s fate on its head.

This has locals, who have seen what happens to people’s air, water, and communities when deserts are transformed into oil fields, worried.

“I just wanted y’all to see it before it happens,” said Paul Matta, 47, a school board member who works for the local housing authority and suspects his way of life will disappear with the arrival of heavy industry in his quiet town, a grid of brightly painted homes, tourist shops, and a single restaurant.

Paul Matta surveys Lake Balmorhea near Balmorhea State Park. In the distance, an orange flare on a recently constructed wellpad burns. Photo Credit: Laura Evangelisto, © 2016.

The prospect of allowing thousands of wells to be fracked where water is so scarce raises fundamental questions about what natural resources Americans are willing to sacrifice in the pursuit of fracked oil and gas, Matta and other Balmorhea locals say. Though the drilling industry long denied that fracking puts water wells at risk of contamination, a major EPA study released in December concluded that drilling and fracking can pose serious risks to people’s drinking water, and has already left some of the country’s water supplies “unusable.”

In many ways, the risks Balmorhea’s wild areas now face have been previewed in wildernesses around the world.

“The amount of wilderness loss in just two decades is staggering,” Dr. Oscar Venter of the University of Northern British Colombia told National Geographic in 2016. Dr. Venter authored a study concluding that in the past two decades, the world lost 23 percent of its wilderness areas. “We need to recognize that wilderness areas, which we’ve foolishly considered to be de-facto protected due to their remoteness, is actually being dramatically lost around the world.”

Balmorhea Blue(s)

Ask a local here what makes their region unique and the facts start spilling out. There’s the nearby Marfa lights, which have drawn conspiracy theorists and UFO enthusiasts for decades, and the tiny church building where, local legend has it, Dillinger hid out from the feds in the 1930s.

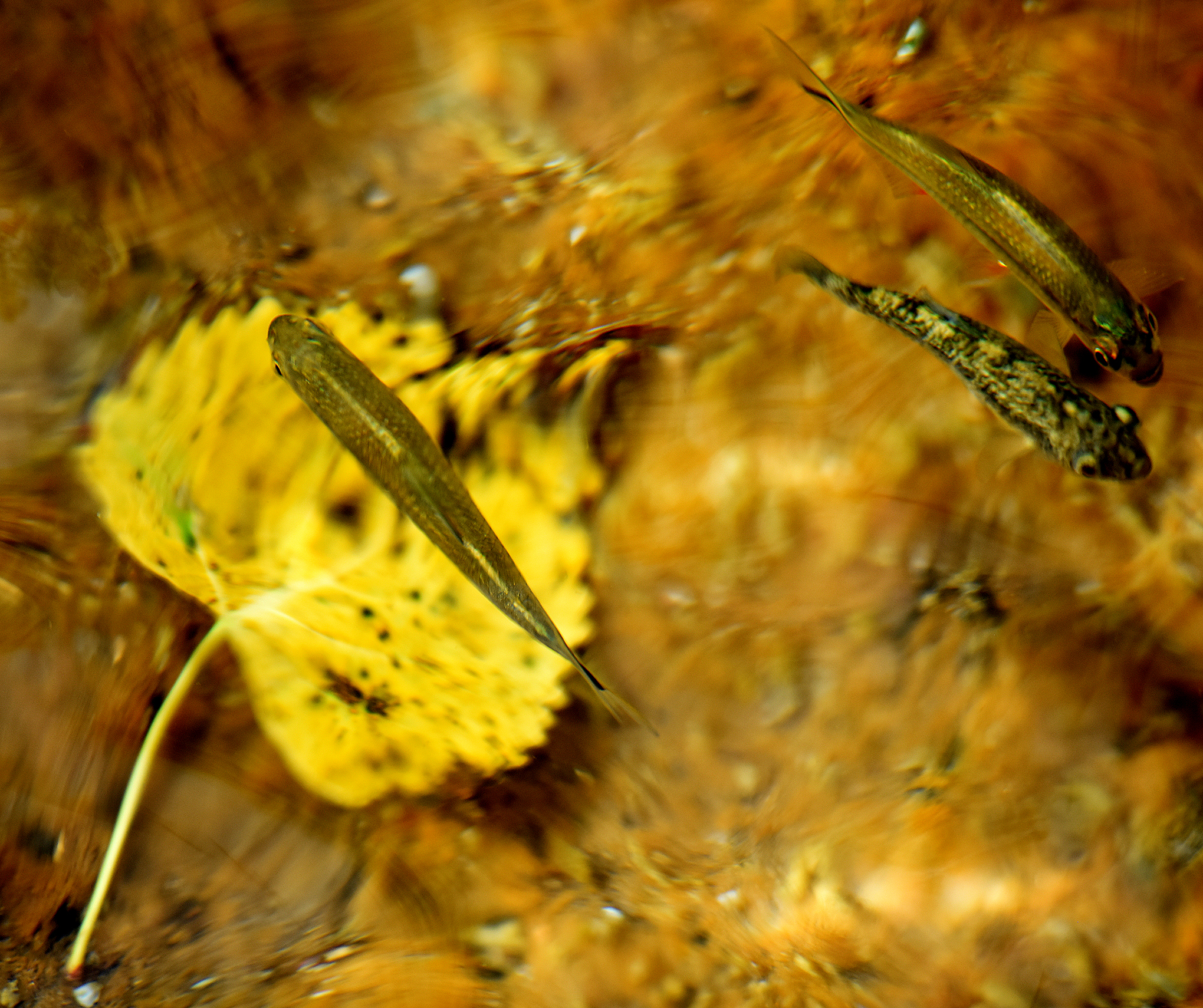

The endangered Comanche Springs Pupfish swims with Pecos gambusia, another endangered fish species, in Balmorhea State Park’s spring-fed pool. Photo Credit: Laura Evangelisto, © 2016.

There’s the Phantom Cave springs, where divers probed depths of over 462 feet in 2013, marking the springs as the deepest underwater cave ever discovered in the U.S. (divers were forced to turn back not because they touched bottom, but because their equipment was at its limits).

There’s the Comanche Springs Pupfish, a two-inch endangered fish named for its puppy-like behaviors, that can only be found in Balmorhea State Park’s springs (ever since nearby Comanche Springs went dry in 1955) — meaning that swimmers at the spring-fed pool share the waters with hundreds of tiny fish found nowhere else in the world.

Even the rocks here can surprise you — pick up an ordinary-looking pebble here, break it open, and you might find a Balmorhea Blue agate, a blue-gray-white swirl of volcanic rock inside a brownish crust. These agates are a tangible hint that (unlike most shale oil and gas prospects), Alpine High lies in the foothills of a volcanic rock formation. The sharp cliffs of the Davis Mountains were formed by volcanic eruptions over 25 million years ago.

These days, it’s not volcanic eruptions but blazing natural gas flares that light up the evening skies, so bright that from the horizon they could be mistaken for the last edge of a setting sun.

A natural gas flare lights up the desert near Balmorhea. Photo Credit: Laura Evangelisto, © 2016.

The flares accompanied the earliest stages of the drilling which Apache plans for here. The company estimates that it will pump over 3 billion barrels of oil from the field, which it dubbed Alpine High, at $50 a barrel, plus 75 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. To put that in context, the industry predicts about three times as much oil and gas from the Marcellus Shale — but that prospect stretches across roughly 90,000 square miles, including most of Pennsylvania and into other states, including New York, West Virginia, and Ohio.

By contrast, Apache’s Alpine High acreage represents roughly 500 square miles of land, and the oil and gas that the company seeks to drill lies in stacked layers of rock formations underground.

“This really is a giant onion that is going to take us years and years to peel back and uncover,” Apache’s Chief Executive Officer John Christmann told analysts at a Barclays conference in September.

Energy industry analysts have been abuzz about the discovery, marketed as the biggest find of 2016.

“How important is it?” Andrew McConn, a Wood Mackenzie analyst, said to the Houston Chronicle in December. “I’d say very important.”

In September, Apache announced it had leased more than 300,000 acres of continuous parcels of land in the Alpine High prospect, allowing it to drill 3,000 or more oil and gas wells in Reeves County. So far, a relatively small number of wells have been drilled and fracked — less than a dozen as of August 2016.

For Paul Matta, Apache’s arrival has already brought a series of nagging worries, not just concern that drilling accidents and chemical spills could contaminate the region’s unique springs, but also the risk that the water-thirsty process of fracking will parch the springs dry. He also fears that seismic activity, whether from earthquakes or simply heavy machinery and industrial activity, could shift the spring’s underground geology, stopping the water from naturally flowing to the surface.

Apache has promised to “minimize” its use of fresh spring water during drilling and fracking. The company also says it will take extra steps to protect the local springs, including a plan to refrain from drilling under the state park and town, even though it has leased the oil and gas rights there. The driller is also funding research to document the current state of the area’s water and is working with the local observatory to try and keep light pollution down, company spokesperson Castlen Kennedy told DeSmog.

“Alpine High is a multi-decade commitment for Apache Corp. as is the protection and well being of the surrounding communities,” she said in an email.

The company’s promises were met with skepticism in Balmorhea. “Apache says they’re going to transport in brackish water but — from where?,” said Matta, gesturing towards the desert around him. “Who’s going to monitor that?”

It’s no secret that the oil and gas industry wields enormous political power here in Texas — leaving residents with little reassurance that their town and its environment will be protected. “People just say, oh well, that’s Texas, and they don’t report on it,” Sharon Wilson, an organizer with Earthworks, told DeSmog, “but there is a lot of opposition to the oil and gas industry in Texas.”

And what happens out in this corner of Texas — so remote that locals say they make the multi-hour trek out to a grocery store just once a month — not only could put locals at risk, it could also affect the entire planet’s fate.

In October, Earthworks visited Reeves County and recorded plumes of methane leaking out of tanks, compressor stations, and drilling sites, using a special FLIR camera to reveal the normally invisible gas clouds. Methane, a greenhouse gas that’s 86 times more powerful than carbon dioxide, has scientists warning that leaks from oil and gas equipment could release enough greenhouse gases that relying on natural gas instead of coal for electricity might be a step backwards for the climate.

And in Texas, environmentalists say that little is being done by state regulators to curb the oil industry’s methane leaks.

“It doesn’t matter what rules they make in Colorado or even federal rules to stop all the methane blasting into the air, Texas doesn’t abide by that,” Wilson said. “Whatever any other state does, it’s nothing like what I’ve seen in Texas.”

“Everything Is in Favor of the Oil and Against Us”

From metal rocking chairs on their front porch, Neta and Darrel Rhyne sat with Paul Matta and mulled over the fate of Balmorhea in the face of Apache’s arrival.

“I’ve been in a hot air balloon, and we went up and so you see Phantom Springs, San Solomon Springs, Giffen Springs, and you see all of the water flowing towards town off of these two springs,” said Neta, “and it’s just amazing, in the Chihuahua Desert that we have this.”

The two run a SCUBA shop near the state park, supplying gear to tourists who visit from around the world to dive the local springs and to brush shoulders with an increasingly rare way of life.

Neta Rhyne sits on the porch in front of the dive shop she runs with her husband Darrel near Balmorhea State Park. Photo Credit: Laura Evangelisto, © 2016.

“West Texas,” said Neta, “to tourists, West Texas is the cowboy and the old west and it’s really the — this is really the only place that’s not been touched.”

Apache has said it plans to drill 3,000 or more wells to tap the Alpine Heights oilfield. “And talk about the infrastructure that has to come along with 3,000 wells, ” said Neta. “You got to have man camps, you have to have roads, you have to have transportation to haul out what you’re pumping out. You have to feed these people. How the — where are they going to do that? It doesn’t exist right now. So what kind of footprint are they going to be bringing to this desert oasis?”

Drilling and fracking could harm the springs many different ways, an in-depth analysis commissioned by Earthworks concluded in November. The researchers found threats were posed by spills, underground migration of gas or chemicals, and changes to the artesian pressures underground.

The Rhynes worry that if the water here goes bad, they will face a nearly impossible battle to hold the driller accountable. A researcher from a nearby university had offered to conduct water tests, but then gave media interviews supporting Apache, causing the couple to worry that his loyalty might lie with the company if a legal dispute arose. Independently testing their four water wells before drilling started would cost $55,000, the couple was told.

“That’s a lot of money,” Neta said. “I mean, where do working class folks like us go to get this?”

Even if they could afford it, there’s little guarantee that independent water tests would cover whatever problems might emerge. “Nobody knows the chemicals they’re using,” Neta said. “They don’t even have to tell the regulatory agencies what chemicals they’re using. So how — how do you protect yourself? It just — everything is in favor of the oil and against us. Everything.”

“It’s kind of like Balmorhea is not going to have much of a voice,” added Darrel. “You know, it’s a very small rural community of probably 90 percent Hispanic or other minorities.”

The oil industry in Texas has a history of problems with environmental racism, with one study last year finding that fracking wastewater wells were disproportionately concentrated in low-income and Hispanic neighborhoods in Texas’ Eagle Ford shale region.

Born in Oklahoma and Texas respectively, Neta and Darrel grew up around the oil industry, living together in an area called “refinery row” in the early 1980s. Then in 1984 Darrel was appointed manager of the state park, and he and Neta moved out to the desert.

“Really at that time, we thought it was just a step with the park service,” Darrel said, explaining that they had lived along the coastline but once they arrived in the Balmorhea desert, they didn’t want to leave. “We moved out here and we feel like we hit home, we found home.”

But putting down roots in Balmorhea was more than just a career move — Neta credits the clean air here with saving her life. “I had lung cancer in ’92,” Neta explained. “I was — used to be a smoker. And they gave me two months to live.”

Over twenty years later, that lung cancer has yet to return. “My oncologist still shakes his head, and says ‘I don’t know why you’re here, but …’” Neta said with a laugh.

The night skies of West Texas may soon face more light pollution as drilling and flaring extend further into the desert. Photo Credit: Laura Evangelisto, © 2016.

“The clean air, you know, I felt safe staying here,” she explained. “Because we don’t have the pollution, we have clean air, we have beautiful dark skies, and well that’s — that’s gone now. It’s already gone, and they’ve just started.”

That loss seemed to sit heavy on Neta’s shoulders. “This is our livelihood, this is our home, this is where we planned for all of our future generations to live and exist,” she said. “Now what? It’s going to be turned into a desert wasteland, a dust bowl before they’re done — and how do you live with that? How do you accept that? And how do you live with the fact there’s not anything you can do about it?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “I haven’t figured that out yet.”

For now, the couple is instead working on figuring out how to prevent Balmorhea from turning into little more than another oil field. They’ve helped form a grassroots group called Save Our Springs Too and organized community meetings for locals to learn about drilling and to discuss the risks posed.

In late December, the Rhynes announced that they would welcome those concerned about fracking around Balmorhea and neighboring Toyahvale, Texas, to come visit and to camp out on their land.

“We’re going to get Toyahvale on the map, finally,” Neta told the Houston Chronicle. “Wish it were for better reasons.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts