A new government report finds that only 9 percent of all the rail tank cars transporting flammable liquids last year met the stricter safety requirements of regulations set in 2015, which were meant to reduce oil train explosions and accidents. This confirms what DeSmog reported last year showing that the oil and rail industries were not moving to aggressively upgrade the fleet to the higher safety standards. Of course, the regulations gave them over a decade to make the upgrades and provided little incentive for industry to move faster.

In 2015 the Department of Transportation (DOT) mandated that industry phase out the thinner-shelled and more accident-prone DOT-111 tank cars and instead carry flammable liquids in DOT-117 cars, a newer, safer design for hazardous cargo.

What’s perhaps more alarming than the slow progress in improving rail safety is the report’s projection for when rail car fleets are likely to meet the new standards for transporting crude oil: 2029.

That means that it will be over 15 years since the deadly accident in Lac-Megantic, Quebec, when unattended DOT-111 tank cars carrying crude oil caught fire and exploded, killing dozens. And it will be over 30 years since the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) first warned against moving flammable liquids in the unsafe DOT-111 tankers.

However, to be fair, if the industry does manage to meet the 2029 deadline, it will have met that goal much faster than the NTSB recommendation to implement the safety technology known as positive train control. That recommendation was first made in 1970 and the industry still has not implemented the technology.

Some Good News on Crude Oil and DOT-111’s

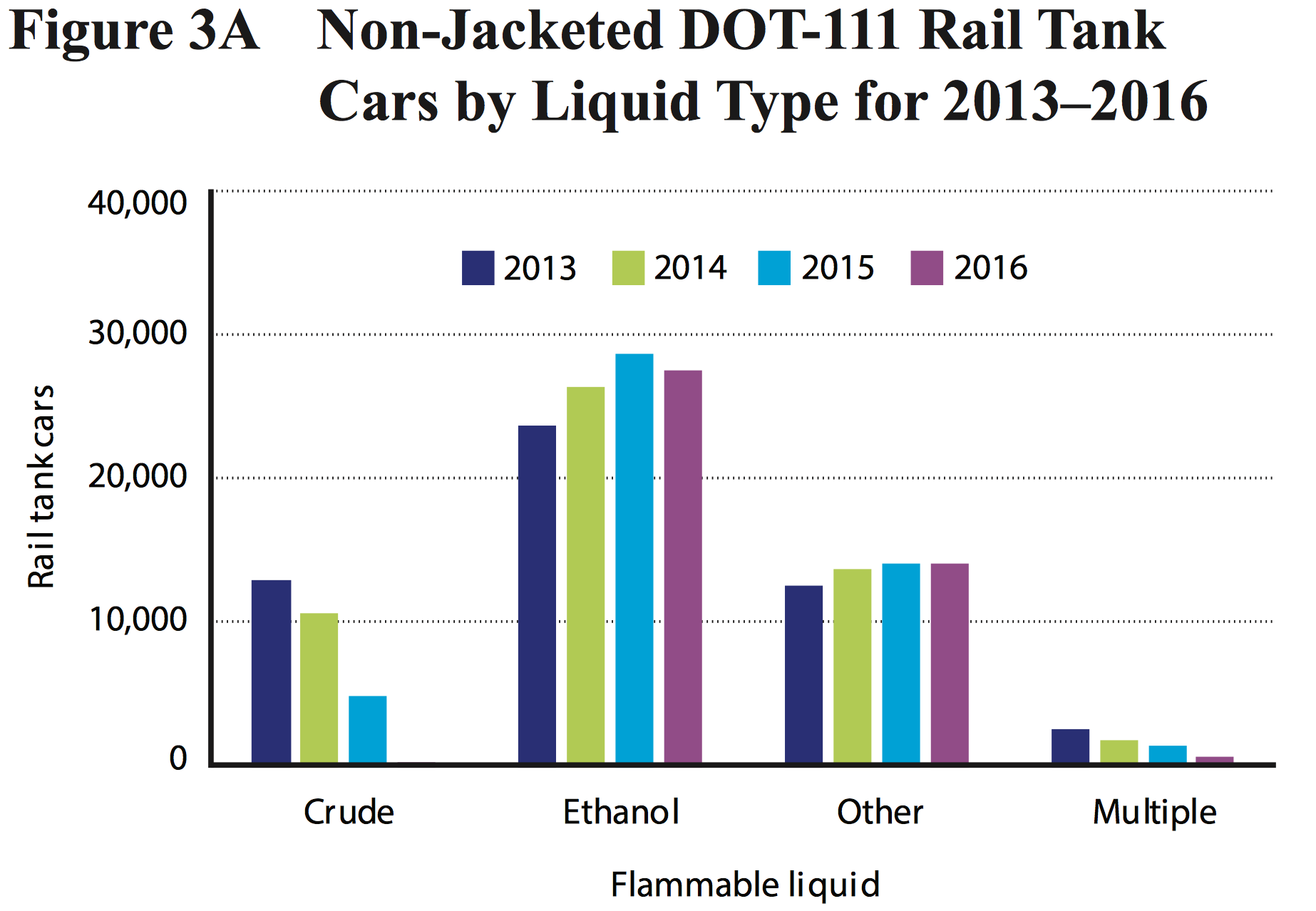

The good news in the new DOT report is that the industry has mostly stopped using the most dangerous non-jacketed DOT-111’s to move crude oil. However, this transition has been eased because lower volumes of crude oil are being moved overall. As you can see in Figure 3A, the number of these tanks cars moving ethanol has actually increased since 2013.

Source: Fleet Composition of Rail Tank Cars That Transport Flammable Liquids: 2013–2016

Government rules allow ethanol shippers to continue using the DOT-111’s much longer than crude oil, which means the risk has been shifted from one product to another. The riskiest non-jacketed DOT-111 tank cars can carry ethanol until May 2023.

Last year at a roundtable event on oil and ethanol train safety, Robert Sumwalt, a member of the NTSB, said, “We would like to see the shippers accelerate their schedule to get these legacy DOT-111 tank cars out of service when transporting flammable liquids — specifically crude oil and ethanol.”

While that is now mostly the case for crude oil, the situation has gotten worse for ethanol trains, a scenario that will most likely remain the status quo until 2023. Historically, the delay between what the NTSB would like and what the industry actually does when it comes to safety can have a gap of several decades.

Additionally, while any safety improvements for moving crude oil by rail are welcome, the majority of derailments resulting in explosions and large oil spills in the past few years have not involved the DOT-111s but instead the much newer CPC-1232 tank cars. These are the rail tank cars moving the most crude oil now and will continue to be for many years.

While 2029 can’t come soon enough for the millions of people living within the blast zone of rail tracks transporting crude oil and ethanol, that won’t guarantee safety. Both the oil and rail industries are fighting the implementation of other safety measures that would prevent the so-called “bomb train” phenomena from continuing past 2029.

DOT‘s latest regulations require crude oil trains to phase in modernized braking systems by 2021. However, as noted on DeSmog, the rail industry has made repeated attempts to reverse this regulation and with the Trump administration’s approach to regulation, it is likely this safety rule will be delayed or repealed.

Additionally, the volatile Bakken oil involved in the bomb train phenomena has yet to be regulated by the federal government. If the oil was required to be stabilized prior to shipment, the risk of fires and explosions likely would be greatly reduced. Until that time, transporting crude oil by rail will continue to carry serious risks.

And while the DOT-117 cars definitely reduce the risk of punctures and spills in derailments, we haven’t yet seen what happens to them in an accident when they are carrying crude oil. Just like the CPC-1232 cars have proven to be unsafe in derailments, we may find the same occurs with the DOT-117 tank cars. Which is why regulations requiring modern braking systems and the stabilization of the oil would help improve safety, regardless of which tank car is being used.

A Decade More of Increased Risk

2017 has been a good year for oil trains. There has only been one major derailment and spill so far, and in that case, the oil did not ignite. Meanwhile, there have been two ethanol derailments, with one resulting in a fire and explosions. As we have noted on DeSmog, more ethanol derailments are likely as the ethanol industry begins to follow the patterns of the oil industry and shift to extremely long unit trains (which carry a single product).

However, this bit of luck for the oil industry is largely due to the much smaller volumes of crude oil being moved this year due to the low price of oil and the opening of the Dakota Access pipeline. It is unlikely oil prices will remain at low levels until 2029, meaning the risk posed by Bakken bomb trains remains real. Again, the oil and rail industries continue to fight safety protocols that could reduce this risk, prolonging them as least another decade.

Just recently politicians in Oregon requested rail company BNSF stop running oil trains through the Columbia River Gorge while there were active forest fires. BNSF refused.

A recent paper from the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago concludes that oil-by-rail is here to stay. It found that when the price is right, industry will ramp up oil-by-rail volumes. A recent example of this occurred during Hurricane Harvey, when prices and logistics made it favorable for an East Coast refinery to resume oil-by-rail shipments.

“What rail is very good at is responding to conditions as the oil market changes,” said Ryan Kellogg, one of the paper’s authors. “When the oil market says, ‘Hey there’s a bunch of oil coming out of location C,’ rail is relatively easy to ramp up and get going, or ramp down if there’s a market downturn.”

Anthony Foxx was Secretary of the Department of Transportation when it developed the current regulations for rail fleets transporting oil and ethanol. After the regulations were released, The Hill reported that “Foxx said industry input was very important in the regulatory process.”

“We could have both been more aggressive,” Foxx said.

Main image: The newer, safer DOT-117 tank cars for transporting crude oil and ethanol. Credit: Justin Mikulka

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts