Louisiana’s first-term attorney general Jeff Landry often presents himself as a staunch tough-on-crime and anti-corruption candidate, pushing his office’s powers to the limits (and beyond) as he seeks to lock up offenders.

But when it comes to prosecuting companies for environmental crimes, Landry arrived in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, at the Shale Insight conference with a very different message: sometimes, mistakes happen.

“And so I think that everyone should get an opportunity to get a break the first time,” he told the audience of shale drilling executives.

“But it’s the question of — when you make that mistake, don’t make that same mistake twice,” Landry said.

“And, you know, when you see repeat offenders, certainly those are the kinds of people that seem problematic to me,” he continued, “and I think they’re a small percentage of this particular industry.”

Tough on Crime — for Everyone Else?

The attitude Louisiana’s top prosecutor revealed at this fossil fuel industry gathering was a stark departure from his usual hard-line stance on crime.

Earlier this year Landry decried a police misconduct consent decree between New Orleans and the feds, which was reached after a 2010 Department of Justice investigation found “strong indications of discriminatory policing” and that officers “routinely use unnecessary and unreasonable force.” Landry notoriously labeled such reforms as “hug-a-thug crime fighting policy.”

He even launched his own “Violent Crime Task Force,” though it quickly became embroiled in controversy when it turned out to be arresting people for minor, non-violent crimes, including ones that usually carried only fines, like possessing small quantities of marijuana. (When a federal judge pointed out that the state attorney general’s office generally has no authority to usurp the jobs of local police by going out and arresting people — for important constitutional reasons, the judge noted — Landry quietly disbanded his task force.)

He hails from a state that’s been dubbed the “incarceration capital of the world.” “Louisiana locks up its citizens at a rate 13 times higher than China, five times higher than Iran, and far higher than anywhere else in the United States,” Slate reported earlier this year.

Louisiana prosecutors don’t seem real big on second chances, either. Among the state’s approximately 38,000 incarcerated are roughly 300 prisoners who were sentenced as juveniles to serve life in prison without an opportunity to ever be paroled — a sentence so harsh that, as the Times-Picayune reported, “[i]n two different cases, the [U.S.] Supreme Court has ruled that Louisiana’s practice of sentencing juveniles to life without parole is cruel, and should only be used in rare circumstances.”

The state is also home to Angola, the country’s largest maximum security prison, where over 5,000 people are serving sentences so long that 95 percent are expected to die while locked up.

When he spoke to the industry that also happens to be his largest campaign donor, however, AG Landry struck a very forgiving tone on law enforcement.

An Uncertain EPA Moves Slowly Under Trump

The Shale Insight panel, titled “Managing Attorney General Investigations: Increased State Environmental Enforcement and How You Can Survive,” was moderated by Ronald Levine, Chair of the Internal Investigations and the White Collar Defense Group at the law firm Post & Schell.

During a Shale Insight 2017 discussion panel featuring Attorney General Jeff Landry (middle), discussion moderators display a slide reading “How to Prevent Enforcement” that advises, in part, “Get to know the regulators and ask questions.” Credit: Sharon Kelly

Levine said he was focused on the role of state attorneys general given that in the current political environment, federal prosecutors at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under Scott Pruitt have already seemed to be moving far less aggressively to enforce the law.

“And what I’m kind of seeing and hearing from them — and these are folks, lawyers, in regional offices — is that there’s a lot of uncertainty about where the federal EPA is going, and admit perhaps some confusion,” Levine said. “And as result, things have slowed down considerably.”

While Landry’s office landed in hot water for investigating crimes like drug possession in New Orleans without clear legal authority, he described a very different approach when it comes to his power to investigate environmental crimes, which, like violent crimes, can hurt people or put their health at risk.

“We do have a criminal division under the Attorney General’s office, I don’t know that we engage in a whole lot of environmental investigations,” Landry told the crowd, adding that most environmental problems can be handled administratively through the state’s Department of Environmental Quality, without prosecutors getting involved.

An ‘Un-Bashing Supporter’

One might expect a top law enforcement official to arrive at an industry conference to talk about recent changes to environmental laws, such as how state laws vary, or how to make sure your company is really complying with the rules. And that was exactly what the state official from Ohio discussed at Shale Insight.

“I think the companies that are most successful do have that knowledge [of state laws] and don’t come in and say, ‘well, that’s not how we do it somewhere else,’ — that just doesn’t fly with our office,” Molly Corey, a Senior Assistant Attorney General from Ohio, said.

Though the Shale Insight conference is focused on the Marcellus and Utica shale regions, which include Ohio as well as New York, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania, Landry was the only attorney general on the panel. Pennsylvania’s attorney general was invited to participate, moderators noted, but had declined.

Louisiana’s Landry, in contrast, traveled to the Pittsburgh conference with a very clear message.

“I am — and make no bones about it — a un-bashing [sic] supporter of oil and gas and our energy sector here in this country,” Landry said as the panel kicked off.

Criminal Acts

Landry said he saw the slowing of federal law enforcement under the Trump administration — at least where the environment is concerned — as a plus.

Landry, a Republican who served one term in the House of Representatives, took that office not long after the Deepwater Horizon disaster and described his district as “ground zero for that incident.”

Nonetheless, he told conference attendees he felt that Obama’s EPA had let the wind industry off the hook by failing to prosecute Migratory Bird Act violations, but had been too aggressive on other environmental crimes.

“So I commend the [Trump] administration for trying to slow down that particular process and making sure that we go about ensuring that the playing field is level,” he said.

“I think that states are in a much better position to conduct those types of investigation,” he added, “because I believe that government closest to the people governs best.”

As for his current state-level role, Landry described his own deep philosophical doubts about whether a business can really even commit a crime, because crimes often require prosecutors to prove that a defendant didn’t just perform a criminal act, but that their intention was criminally culpable as well. “And when business are involved and you’re talking about different layers of employment responsibility, it becomes very problematic in my opinion to prove that mens rea,” Landry said, using the Latin term for criminal intent.

Landry pointed to a case from Ohio as an example where he thought prosecution had been appropriate, involving a small wastewater company whose owner pled guilty to deliberately dumping thousands of gallons of fracking wastewater. He contrasted that against another case of intentional dumping where he said he fought Department of Justice attorneys who thought that a company’s management should be prosecuted, while Landry argued that only one worker, a “disgruntled” man who had actually opened up a wastewater valve, was responsible for illegal dumping.

It’s worth noting that some environmental rules specifically hold defendants responsible for negligent or even unintentional dumping, not just deliberate wrong-doing, though accidents generally carry lesser punishments. Those kinds of laws are usually written to impose a duty on people or companies to actively prevent accidents because public safety could be gravely endangered.

At one point Landry’s remarks on criminal intent drew some minor pushback from Levine, the defense attorney. “There are federal statutes out there that don’t require an intent to cheat,” Levine pointed out.

Paying Dividends

For the rest of the shale drilling industry, and the Marcellus Shale Coalition which hosted the event, Landry suggested that they focus their efforts more on helping to write the laws that govern them.

“I would — one of the things that I would offer, is I think this Coalition, and people in the industry need to get involved in the political process, ” he said, “because I think that industry absolutely has the best standards.”

Companies could face policing by federal regulators, who he said “couldn’t tell you which end of the drill bit goes on the rig much less tell you what went wrong with your rig, but yet they’re going to sit there and want to impose fines and violations for things that they suppose but they have no actual absolute real-world experience.”

On the other hand, Landry, who collected roughly $480,000 from oil and gas industry campaign contributions from 2009-2018, according to Open Secrets, suggested that there was perhaps another option.

“But going out and trying to get involved in the political process on the front end,” he said, “certainly I think pays a tremendous amount of dividends.”

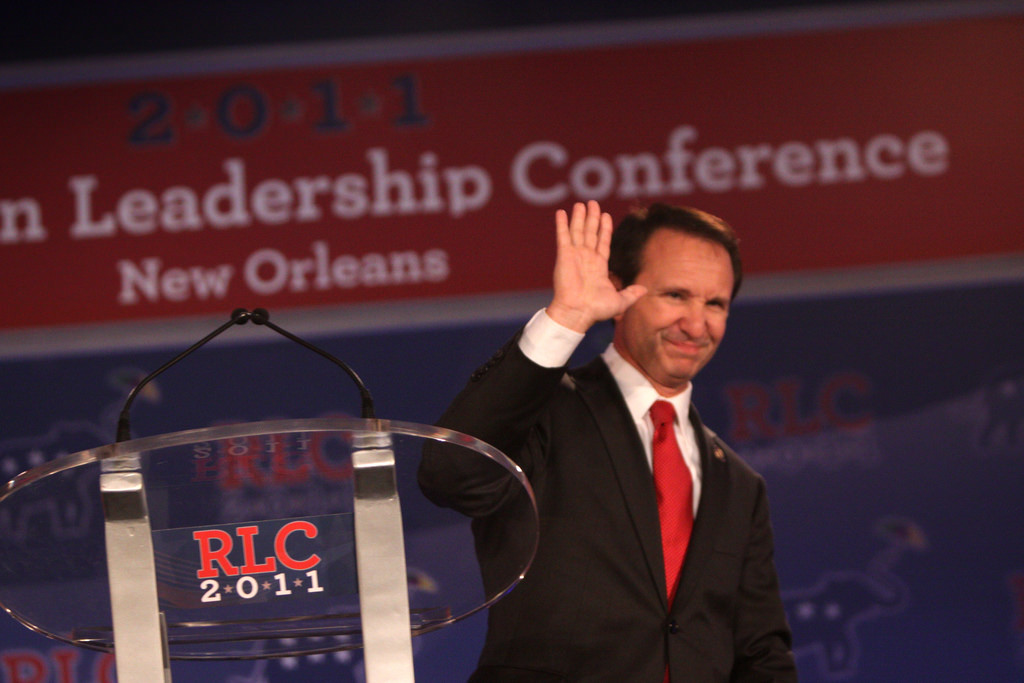

Main image: Congressman Jeff Landry at the 2011 Republican Leadership Conference. Credit: Gage Skidmore, CC BY–SA 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts