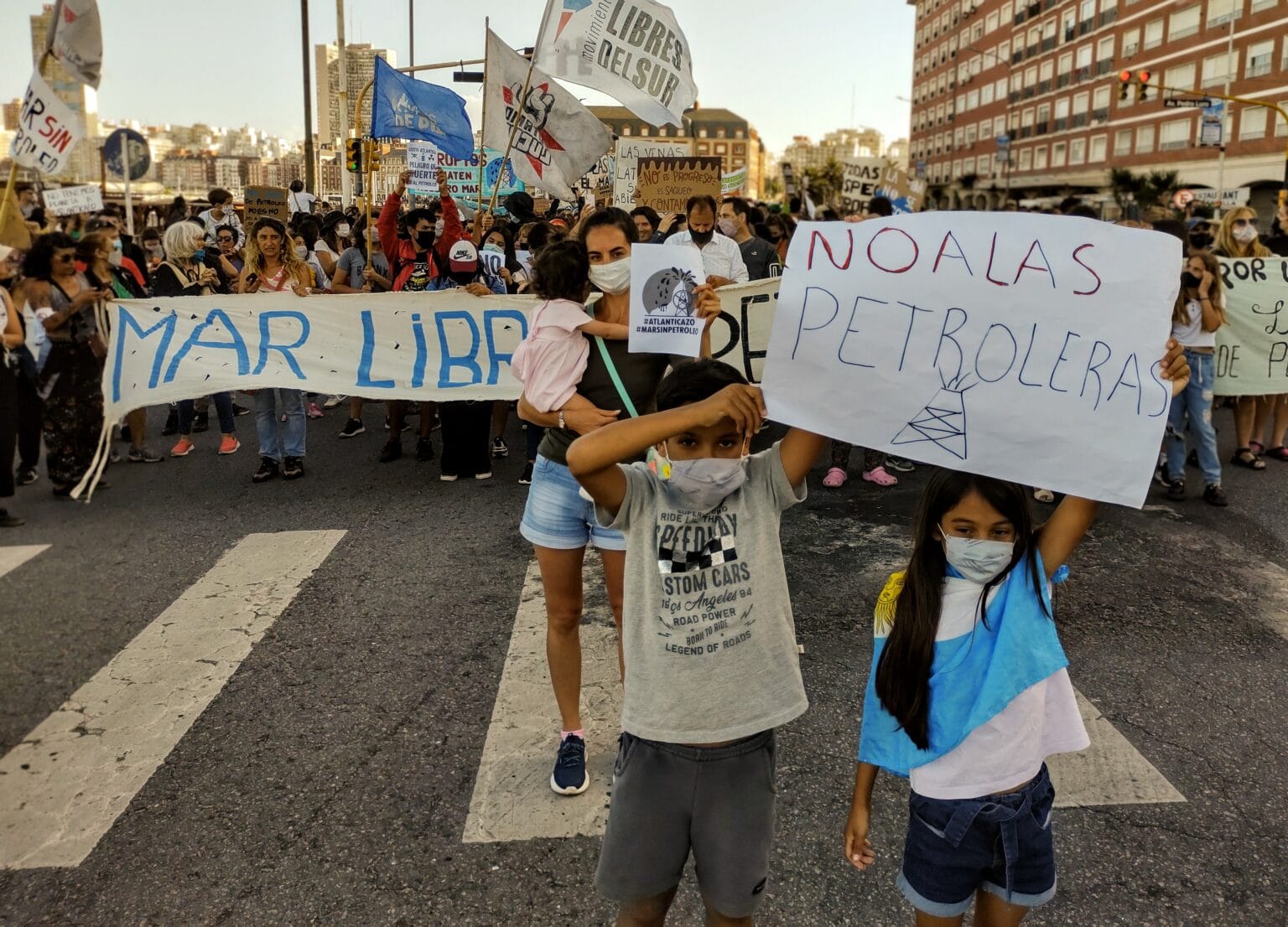

On January 4, thousands of people took to the streets of Mar del Plata, a coastal city roughly 250 miles south of Buenos Aires, Argentina. They were there to protest the plans by Norwegian oil company Equinor to begin offshore oil exploration later this year.

They held signs that read “the sea is ours!” and “an ocean free of oil,” and they chanted, shouted, and sang. The protests were focused in Mar del Plata, a beach town closest to the offshore blocks, but spread to other cities in the province and around the country.

The protesters oppose offshore drilling because of the risks of an oil spill, which could wreck tourism and interfere with fishing, two important parts of the coastal economy. They also fear that the seismic tests that accompany oil exploration would pose a mortal threat to southern right whales and could harm abundant marine life.

More broadly, protesters are frustrated that Argentine officials continuously promote oil, gas, and mining projects as economic godsends, while ignoring the impacts to communities where they are located.

“The outrage is because they advance with these extractivist projects to benefit the corporations, despite the environmental and social impact that they will generate in our territory,” Fernanda Génova, a Mar del Plata-based member of the Assembly for a Sea Free of Oil Companies (la Asamblea por un Mar Libre de Petroleras), told DeSmog. The Assembly is a network of social, environmental, and political groups that have banded together to oppose offshore oil drilling along Argentina’s Atlantic coast.

Oil projects are “imposed on us” by the state, Génova said, “with a false discourse of job creation.” But behind the state-backed pro-oil narrative, she added, is a campaign of “looting and dispossession of our territories.”

Argentina Pushes for Offshore Drilling

Argentina is a minor player in the offshore oil industry, especially compared to its neighbor Brazil, which has long been a global leader in deepwater drilling. But a public auction for offshore blocks off the coast of Buenos Aires, held in 2019, is viewed by the government and the handful of oil companies as a potential turning point.

Led by Equinor, but also including Shell and the quasi-state-owned Argentine oil company YPF — and with the backing of the national government — the industry has big plans for drilling offshore. The 2019 auction was the first offshore offering in more than 20 years, and yielded $720 million in bids from 13 companies. The government licensed a total of 18 blocks, but three held by Equinor are viewed by industry analysts as particularly attractive.

The timing of the next steps is not entirely clear, but Equinor hopes to do seismic testing, a mapping technique that is a precursor to drilling, later this year. Meanwhile, YPF has suggested it wants to drill a well before the year is out.

In January, YPF chief executive Pablo Gonzalez told S&P Global Platts that there is “enormous potential” offshore and that the oil and gas reserves “could equal those in Vaca Muerta,” the shale formation in Argentina’s arid interior that is home to a state-subsidized fracking boom.

One particular block that YPF, Shell, and Equinor plan on developing together — CAN 100 — could result in 200,000 barrels of oil per day, he said, which would be roughly equivalent to a third of the country’s entire current oil production of around 550,000 barrels per day. The CAN 100 project alone could cost as much as $6 billion.

Gonzalez pointed to Brazil as a model. “The countries that bet on offshore development achieved a very positive impact on the economy of their countries, without affecting the environment,” he said in the article. “The case of Brazil serves as an example of how this path of reconciling economic development and environmental sustainability was achieved.”

Before the oil companies could move forward with their development plans, they needed the Argentine government to sign off on an environmental impact assessment. That approval came on December 30, 2021, the last working day of the year, which “took advantage” of the fact that people were celebrating Christmas and the New Year, Génova said, and crystallized what activists see as indifference to public concerns.

The People Push Back

Approval was not a foregone conclusion. The Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development held a public consultation process in July 2021, where opposition to the proposal was clearly evident.

“This hearing was convened only 15 days in advance, with little publicity and little information available so that the affected communities can evaluate the socio-environmental consequences of these projects,” Génova said. “Despite this, the voices against the installation of oil platforms in the sea were in the majority.”

More than 300 people spoke out against the plan, while only a dozen voiced support. In response, the Ministry vowed to not award permits until a more comprehensive national decarbonization strategy was fleshed out.

Given those assurances, the approval on December 30 was a “betrayal,” Ilan Zugman, Latin America managing director at 350.org, told DeSmog in an email.

That set the stage for the big protests on January 4. More than 3,000 people marched in Mar del Plata, a large turnout for a city of approximately 600,000 people. Similar protests were held in front of the Casa Rosada, the presidential palace in Buenos Aires, the nation’s capital. The protests made national headlines and the opposition to drilling has taken on the moniker “Atlanticazo,” using a suffix in Spanish that accentuates the momentousness of the event.

The campaign came as Argentina suffered a historic heat wave that put further emphasis on the climate crisis. Parts of the country saw temperatures in excess of 113 degrees Fahrenheit in mid-January, and the record-setting demand for electricity led to temporary blackouts in Buenos Aires.

In addition, a series of oil spills from around the world in just the past few weeks have offered reminders of the dangers of offshore oil drilling — including in Thailand, Ecuador, and Peru.

Offshore oil drilling not only risks fouling coastlines, but also poses a serious threat to southern right whales, whose feeding grounds overlap with the blocks offered to Equinor, Shell, and YPF in the Atlantic. In October, if all goes according to plan, Equinor will begin seismic testing, which consists of repeatedly blasting air guns at the ocean floor and measuring the noises that bounce back. The information that comes back is then used to map the area.

Whales “depend on the production and perception of sound for most of their vital functions,” Diego Taboada, president of the Buenos Aires-based Institute for the Conservation of Whales (Instituto de Conservación de Ballenas), wrote in an email to DeSmog. The sound from the seismic blasts can travel more than 2,000 miles, which can cause physical damage to whales that can be fatal, he said. The offshore blocks where Equinor and others want to drill also overlap with an area rich in biodiversity that serves as the feeding grounds and migration corridors for a long list of marine animals, including dolphins, penguins, turtles, and birds.

“There is no way that the oil industry can guarantee a low ‘risk’ or impact on biodiversity and, consequently, on the population,” he said. “The activities proposed by Equinor Argentina will degrade an ecosystem that is already threatened by overfishing, global warming and pollution.”

The ‘Chubutazo‘

The protests also drew strength from recent events further south, in the province of Chubut, regarding an entirely separate project. In December, the Chubut legislature passed a law that authorized a highly contentious form of open pit mining that uses cyanide, which would have paved the way for Canadian mining company Pan American Silver to develop one of the world’s largest silver projects. The company’s stock immediately jumped by nearly 9 percent after the law was changed.

The move was highly unpopular. In the lead up to the vote, protesters marched in opposition to the proposed law in various cities around the province, including Trelew and Puerto Madryn. On the day of the vote, police surrounded the provincial legislative building to keep demonstrators away. When the law passed, the public reaction was immediate and intense. Police cracked down on protesters, using tear gas and rubber bullets, while protesters lit tires on fire and threw rocks.

In subsequent days, rather than dying down, the protests intensified, spreading to most major urban areas, including Rawson, Comodoro Rivadavia, Esquel, Trelew, and Puerto Madryn. Workers in shops and supermarkets went on strike. People blocked the two major highways that run north-south along each end of the province. Thousands marched in the streets. The uprising included not just environmental activists, but also dock workers, fishing unions, neighborhood associations, and municipal governments.

The protests culminated with the torching of several government buildings in Rawson, the capital of Chubut. An image of a burned-out government building with the word “traitors” spray painted on the walls spread on social media.

The massive outpouring of anger forced a quick and total retreat by the provincial government. Less than a week after approving the mining law, the legislature rushed back into session to repeal it. People celebrated in the streets following the government’s about-face.

A near identical episode occurred two years earlier, almost to the day, in the province of Mendoza. In December 2019, the provincial legislature scrapped a ban on the use of cyanide for open pit mining, and the city exploded in protest, forcing the government to quickly back down. The events of Mendoza are widely seen as an antecedent to the explosive protests in Chubut at the end of last year.

“Chubut left the lesson that participation is useful and that the political leadership is afraid of the organized society,” Pablo Lada, a Chubut-based environmental activist, told DeSmog. “The same legislature that had passed a law enabling mega-mining, a law that was rejected by all the people of Chubut, had to meet again, forced by the impressive popular demonstrations, perhaps the most important in recent history, and one week later unanimously repealed the law.”

Growing Environmental Movement

The Chubutazo, as it has come to be known, has injected energy into the fight against offshore oil drilling. “It is impossible to disconnect both events,” Lada said. The Atlanticazo was “openly inspired by the events of Chubut.”

But unlike the fight against silver mining in southern Argentina, the opposition to offshore oil drilling has yet to achieve its goals. The drilling campaign has much stronger political backing from the national government, which views its pro-drilling energy policy as critical to its approach to the economy. Offshore oil drilling also involves not just the state-owned oil company YPF, but also a handful of powerful international oil companies that are dangling billions of dollars’ worth of investment.

Nevertheless, some say the ongoing protests of offshore drilling are unprecedented. And taken together, the Chubutazo and the Atlanticazo have demonstrated the growing strength of the environmental movement, as well as a deepening disillusionment with the government of President Alberto Fernandez, who makes bold claims about fighting climate change but whose government consistently supports oil and gas drilling and heavily subsidizes the industry.

A few days after the January 4 protests in Mar del Plata and elsewhere, a public manifesto called “Mira” (“Look”) signed by prominent writers, artists, journalists, actors, musicians, and scientists, publicly criticized not only offshore oil drilling, but more broadly the longstanding approach to economic development, which relies heavily on exporting fossil fuels, minerals, meat, and soy.

“Do not close your eyes, look,” the document states. “Look” at oil spills around the world, it urges, and “look” at how the government subsidizes fossil fuels, but not renewables. “Look at the poverty,” despite promises of riches from fracking and industrial agriculture.

“There is no social license for one more destructive business,” the manifesto states.

But challenging the orthodoxy of digging up and exporting raw materials as a means to grow the economy is difficult. Lurching from one debt crisis to another, government officials consistently argue that increased drilling and mining is even more necessary in light of the crisis of any given moment. Often hemmed in by international creditors and looming debt repayment schedules, the national government across multiple administrations has bet on fracking, mining, and now offshore oil drilling.

Against the backdrop of a chronic debt crisis, the change in position by the Ministry of Environment from skepticism to approving the project, suggests that “the decision has not been a free one,” Zugman said, adding that the government is “disoriented” and is in a state of “political weakness,” which affects decision-making. Boosters at the provincial and federal level make outlandish claims about future revenues from drilling “in the same way as when the exploitation of Vaca Muerta was promoted,” he said.

Equinor did not respond to a request for comment. Argentina’s Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development did not respond to a request for comment.

But for the protesters in Mar del Plata, the risks are not hard to see. “Where fracking was installed, communities lost their regional economies, ecosystems were devastated, water reserves contaminated, the population already suffers from diseases caused by pollution,” Génova said. “The government gives our common goods to the corporations in exchange for a few dollars to pay the external debt, and the population is left with pollution and more poverty.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts