Oil prices surged this year, and natural gas traded at record levels. There are no equivalent metrics to gauge the strength of the global climate movement – but civil disobedience in Britain appears to be hitting an all-time high.

In the past two weeks, hundreds of people have been arrested for blockading fuel depots by climbing over fences, digging tunnels, and clambering on top of oil tankers. Scientists in lab coats have glued themselves to government buildings and doused Shell’s London headquarters with fake oil. But the most memorable moment was provided by an art teacher who somehow managed to work his way to the eighth floor of the building on Wednesday to livestream an emotional plea.

“Like I say, I don’t really want to be doing this, but Shell need to cease all new extraction of fossil fuels — there is no place for them in the world in which my nieces are growing up in,” said the man, who seemed visibly surprised, and a little nervous, at having managed to penetrate so far into the complex. “Shell — I’m pleading you to end the extraction of fossil fuels.”

With Extinction Rebellion and its offshoots once more setting the news agenda, a new documentary charts the rollercoaster of exhilaration, personal epiphanies, and burnout that infused the movement’s early days — with lessons for climate movements around the globe.

Airing on Netflix in the UK, Rebellion was co-directed by Maia Kenworthy and Elena Sánchez Bellot, first-time filmmakers who shot the feature-length documentary over three years while supporting themselves with freelance gigs. Constantly on call to rush to protests, they initially had no funding — nor even a guarantee that the film would ever be screened.

Their perseverance has yielded a gripping work that sheds valuable light on how Extinction Rebellion inspired thousands of volunteers to blockade key sites in the heart of London for two weeks in April, 2019 to demand immediate action on climate change.

It was a marathon act of civil disobedience that reverberated around the world. This sudden success also unleashed internal tensions that underscored the challenge of rapidly scaling social movements pushing for the pace of action that science demands.

‘Dead or Banged Up’

Among the film’s leading protagonists is Farhana Yamin, an environmental lawyer, veteran of countless rounds of UN climate talks, and one of the architects of the Paris Agreement. After decades of fighting for climate justice from within the system, Yamin became so frustrated by the role of fossil fuel companies in hindering progress that she decided to get arrested at the start of the 2019 protests by supergluing herself to the pavement outside Shell’s headquarters.

“Every year Shell spent millions delaying legislation, spent millions confusing people,” Yamin is shown yelling while sprawled on the pavement as police try to remove her. “They did a great job of whitewashing what was going on and I’ve spent 25 years negotiating international agreements that they’ve done their best to thwart. That’s why I’m here.”

While Yamin grapples with the implications of crossing this personal Rubicon into direct action, Roger Hallam, one of the movement’s co-founders, is shown preaching the necessity of disruption with evangelical zeal. “My view is that if you’re not in prison, you’re not in resistance,” he tells Kenworthy and Bellot. “There’s nothing complicated about high sacrifice…You keep going until you’re banged up or dead. That’s what civil resistance means.”

Hallam’s single-minded obsession with getting as many people arrested as possible was critical to the movement’s early momentum. It was also its greatest liability, eclipsing the hopes of many volunteers of capitalising on Extinction Rebellion’s breakthrough moment to build a broader coalition. The crisis reaches breaking point when Hallam’s plan to shut down Heathrow Airport by flying tiny toy drones horrifies supporters who fear the stunt will erode public support.

In one of the most powerful scenes, Hallam’s daughter Savannah, who has joined the protests, walks out of a meeting when it becomes clear that her father cannot hear concerns that the base of the membership feels frozen out.

Competing Visions

Such moments provide an unfiltered insight into the challenge Extinction Rebellion faced in creating a decision-making structure capable of reconciling the aspiration to function as a decentralised, self-organising network with the need for a coherent strategy. While many movements face similar dilemmas, the learning process was compressed into a matter of weeks as Extinction Rebellion exploded into the public sphere from an almost standing start.

This rapid and often painful evolution is also apparent in the struggle by some volunteers to ensure the movement places a greater emphasis on the systemic injustices at the root of the climate crisis.

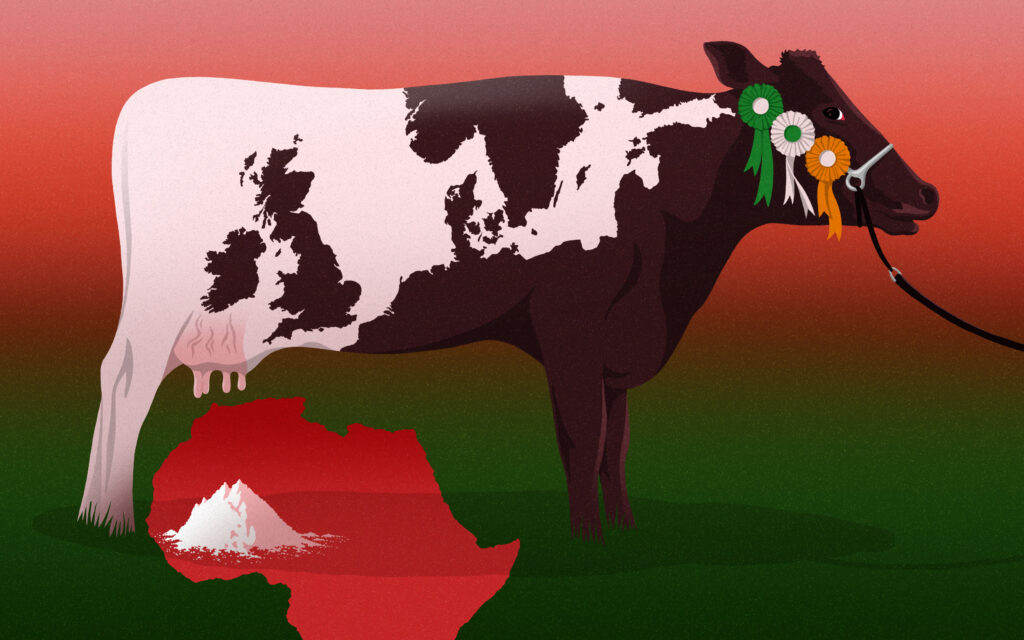

“People were really stuck in this ‘get arrested, get arrested’ mode,” activist Alejandra Piazolla Ramírez tells the filmmakers. “We cannot talk about the climate crisis without talking about justice. Typical white, western environmentalism — they only usually think about emissions, that the only issue is climate change: ‘Why are we wasting any time talking about racism, about colonialism?’”

Despite being shot mostly within the Extinction Rebellion bubble, the film doesn’t shirk from showing how disruptive tactics can backfire. Furious passengers are shown dragging a protester from the roof of a train carriage at Canning Town station in east London during the morning rush-hour. Critics would seize upon the ugly scenes to amplify the right-wing media’s stereotypical portrayal of the activists as privileged “eco-zealots” intent on disrupting the lives of working-class commuters.

Crackdown

The film also conveys how the government uses an appearance of accommodation to camouflage an increasingly draconian response.

Yamin is shown celebrating the moment when the British parliament declares a symbolic climate emergency in response to the protests, telling a reporter outside the assembly: “It works! Rebellion works!” Such declarations have since been made by national assemblies, cities, and councils in many parts of the world. Parliament would also create a Citizens Assembly on climate, apparently in response to one of Extinction Rebellion’s core demands — though the gathering would lack the kind of binding decision-making power demanded by the movement.

These gestures pale relative to the government’s long-term backlash. Policing is shown to be much more intimidating during the second phase of protests in October 2019. The Territorial Support Group public order unit raids Extinction Rebellion premises using a battering ram, and the police ban all the movement’s demonstrations across London — a move later overturned by the High Court.

The film also explores the government’s attempts to give police sweeping powers to curtail protests in a new Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill — currently before parliament — that has been widely condemned by civil liberties groups.

“One of the clearest signs that Extinction Rebellion and other social movements are effective is that the government is trying to make protest this ineffective, semi-pointless exercise in pretending that we’ve actually got a democracy, when we haven’t,” Gail Bradbrook, one of Extinction Rebellion’s co-founders, says in the film.

An Evolving Movement

In the wake of the pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine, it is easy to forget how the “climate spring” of 2019 galvanised attention among government, companies, and investors. Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg was inspiring millions of young people to walk out of class; Extinction Rebellion was dominating the headlines; and many other organisations were amping up their campaigns around the world. It seems fair to assume that this clamour helped spur the government of then prime minister Theresa May to commit Britain to a legally-binding target to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050 — making it the first G7 country to take such a step.

“It was one of those moments where things open up, things that weren’t possible seemed possible,” Sam Knights, a former Extinction Rebellion activist, tells the filmmakers.

Since then, the UK government’s net zero commitment has not translated into credible action. A long-awaited energy policy published last week was widely criticised for failing to take more ambitious steps towards decarbonisation — and pledging to accelerate the exploitation of North Sea oil and gas. A new Net Zero Scrutiny Group of Conservative MPs is intent on using Brexit-style populist tactics to cancel the net zero project altogether.

Current members point out that Extinction Rebellion has evolved since the inception shown in Rebellion, and both Yamin and Hallam have since left. Yamin is now focused on encouraging philanthropic donors to shift resources to the activists and frontline communities most harmed by climate change. Hallam, meanwhile, played a key role in organising last year’s motorway-blocking Insulate Britain protests, and this month’s Just Stop Oil campaign to block fuel depots. He has spent weeks in jail.

Perhaps the film’s signature achievement is to show how joining Extinction Rebellion serves as an antidote to the cognitive dissonance that comes with living in a society that knows the climate and environmental crises pose an existential threat — but carries on as normal. The sense of community allows volunteers to embrace the grief they have been carrying for all that is being lost — and discover the joy of shared victories. As the impacts of climate change hit harder, this visceral experience of collective agency may be one of Extinction Rebellion’s most valuable legacies.

“The system relies on us feeling powerless,” Bradbrook, one of the co-founders, is seen telling a crowd towards the end of the film. “Who’s feeling powerless today? When we come together, we’re not powerless.”

Rebellion can be seen on Netflix UK.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts