Years before Hurricane Katrina levee failures flooded New Orleans, a Louisiana hurricane expert warned federal officials of the potential for the levees to break. Now, Ivor van Heerden, the former deputy director of Louisiana State University’s Hurricane Center, is concerned about the disastrous and potentially lethal consequences of a hurricane hitting a liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminal under construction south of New Orleans.

“Once again we’ve got politicians and state agencies ignoring the facts, just like they did with Hurricane Katrina,” van Heerden said. “We’re going to have another catastrophe.”

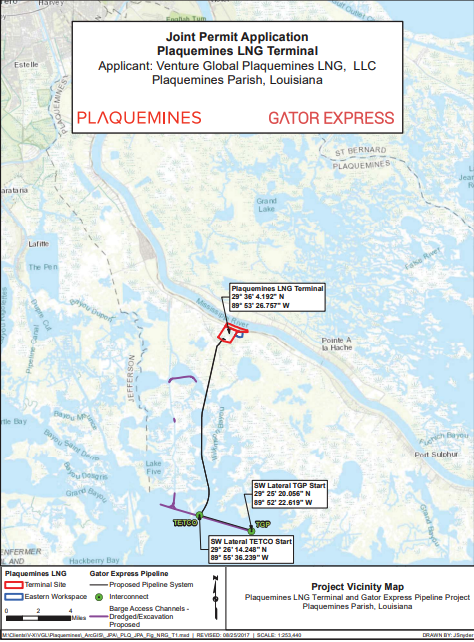

His concerns center on Venture Global’s plans to build an LNG export facility near Black and Indigenous communities in Plaquemines Parish, on a sliver of land between the Mississippi River and wetlands. About 73 percent of the population within 3 miles of the facility’s site are people of color, according to Oil and Gas Watch data.

Van Heerden used National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration modeling to estimate the storm surge a major hurricane in the area near Venture Global’s Plaquemines Parish facility would create. He calculated that storm surge could reach up to 31 feet tall. Waves that high would overtop the ring levee that the company plans to build around the facility, allowing floodwaters to rush through the site. As they did, liquefied natural gas storage tanks could become dislodged and float away, potentially leaking the -256° Fahrenheit liquid inside into nearby homes and surrounding wetlands.

“It will literally freeze anything it comes into contact with and it’s going to float on the water. It’s going to spread quickly,” said van Heerden, who was commissioned by the Sierra Club to assess the location. “When it evaporates, it’s methane. You can’t breathe methane. It will kill you.”

The fact that the facility needs a levee might signal that it should be getting special regulatory scrutiny. The opposite has proven to be true. In 2019, the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources (LDNR) determined that the low-lying site of the planned export terminal didn’t require a coastal use permit, the regulatory tool used by the agency to mitigate damage to the state’s rapidly eroding coastal wetlands.

The agency’s decision was based on the fact that the proposed site is between levees, which classifies the area as “fastlands,” said LDNR spokesperson Patrick Courreges. But neither the existing levees nor the proposed ring levee would prevent a major storm from flooding the site, which was inundated during Hurricane Ida in 2021, van Heerden said. If it’s flooded, it could then pollute the surrounding wetlands, he added.

The residents of Louisiana’s southernmost parish, on the doorstep of Venture Global’s proposed facility, have been asking for more scrutiny in permitting LNG export facilities. They aren’t the only communities of color calling for this: About 400 miles to the east, the Black community in North Port St. Joe, Florida, was caught off guard when they learned that an LNG export facility would be built in the place of a shuttered paper mill.

Nopetro LNG applied for and was approved to be exempt from Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) oversight by claiming that its liquefaction facility is separate from the port where the LNG would be loaded onto ships, even though they are a mere 1,329 ft apart. Because the LNG would be trucked a quarter of a mile to a port for export, the facility does not fall under FERC’s jurisdiction, which only applies to terminals where natural gas is cooled to a liquid and directly loaded onto ships, according to the commission’s decision.

With these permit exemptions, Nopetro LNG and Venture Global avoided lengthy environmental reviews to begin building two polluting facilities as fast as possible near Black communities in the Gulf of Mexico. Neither company responded to requests for comment for this story.

Rush to Slash Regulatory Oversight

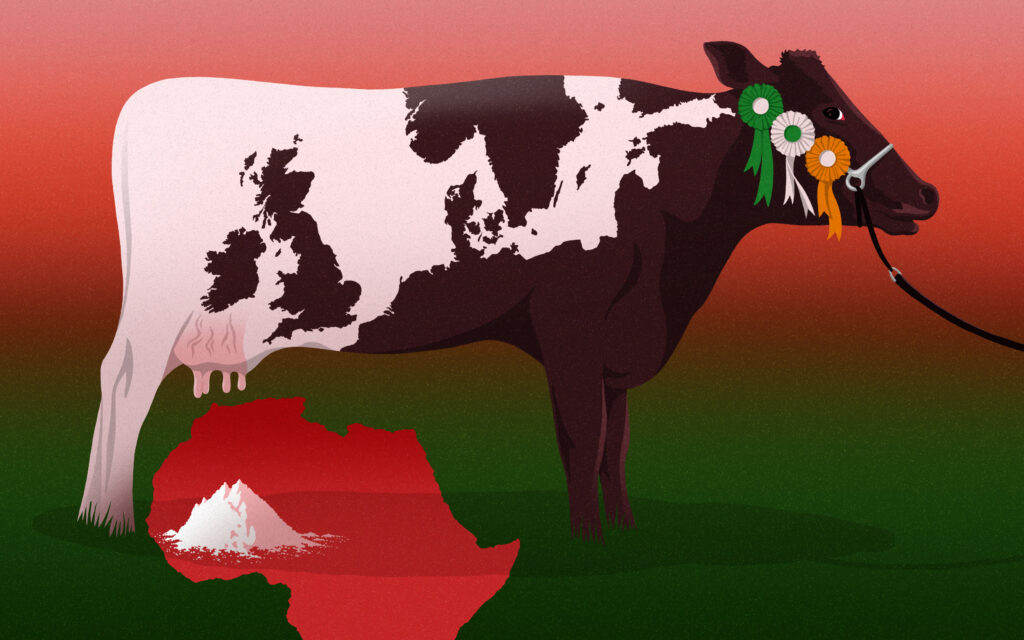

This comes at a time when the industry and politicians are pushing for rapid expansion of natural gas exports and rollbacks of regulatory oversight. Fossil fuel firms have justified their rushed construction plans by pointing to Europe’s scramble to replace Russian natural gas in the wake of the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine last February. In June, German utility EnBW signed a deal with Venture Global to import 1.5 million tonnes per year of LNG for 20 years from the planned Plaquemines Parish LNG terminal and another terminal Venture Global plans to build in Louisiana’s Cameron Parish, known as CP2. In October, the agreement was increased to two million tonnes per year. But more than three-fourths of the U.S-produced LNG under long-term export contracts is destined for the Asia-Pacific region, according to a recent report by energy watchdogs, a sign of Europe’s reluctance to commit to long term contracts for fossil fuels in the face of climate change.

Meanwhile, oil and gas friendly lawmakers have introduced legislation to speed projects by limiting regulatory reviews of gas exports and gas pipelines. “It is past time that we cut the red tape surrounding the natural gas export permitting process, and unleash homegrown American energy,” Rep. Bill Johnson (R-OH) said in a news release about his proposed legislation to roll back restrictions on natural gas exports.

This expedited review process could put an even greater damper on the input of nearby communities of color. Furthermore, while Europe’s thirst for gas is likely short-term, a lack of thorough environmental and public health analyses of LNG export facilities makes them long-term threats to surrounding communities, said Roishetta Ozane, the founder of The Vessel Project of Louisiana, a grassroots mutual aid and disaster relief organization.

Ozane began pushing back against the fossil fuel industry after Hurricane Laura wrecked her home in southwest Louisiana in 2020. “Me and my children lost everything and ended up in a FEMA trailer,” she said. “I just wanted to get to the root of the problem.”

She and other fenceline community leaders traveled to Washington, D.C., during Black History Month this year to urge FERC to stop approving LNG export facilities in the Gulf and protect Black communities. “Communities of color don’t want to be guinea pigs,” Ozane said. Environmental groups have sued regulators over the state permit exemption for the Venture Global facility in Louisiana, the federal permit exemption for the Nopetro facility in Florida, and the Department of Energy for ignoring a petition to establish criteria to determine if LNG exports are in the best interest of the United States.

This month, a judge with the 19th Judicial Court in East Baton Rouge Parish dismissed the case against Louisiana’s Department of Natural Resources (LDNR) for the fastlands classification of the Venture Global site. The ruling was not based on the merits of the case, but whether the case was filed in the right court. The department will wait and see if the plaintiffs appeal or file in Plaquemines Parish, where the judge said the case should be heard, Courreges said.

Lisa Diaz, an attorney with Sierra Club — which filed the lawsuit alongside Healthy Gulf and the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice — called the decision a “small setback.” The groups are considering their next step, she said.

Another LNG export project proposed in a predominantly white community in Louisiana, Commonwealth LNG, submitted an application to LDNR for a Coastal Use Permit in 2019. Records show LDNR still has not approved the permit. “This has been the only facility I’ve run into with a fastlands designation,” Diaz said of the decision to exempt Plaquemines LNG from a Coastal Use Permit.

While Venture Global’s plans include building a 26-foot storm wall around the facility, increases in sea level rise and storm surge height projected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration indicate that may not be enough, van Heerden said. If flooded, chemicals from the LNG export facility could wash off site and pollute the surrounding area, as happened with the Murphy Oil refinery during Hurricane Katrina, he said, when storage tanks leaked oil into 1,700 homes nearby.

The project “will in fact inevitably, irreparably, and significantly harm surge-reducing wetlands, the local community, and the flora and fauna of the area, and will pose a major risk of contaminants escaping the facility during passage of a major hurricane,” van Heerden wrote in an affidavit. The company recently secured $7.8 billion in funding for the next phase of the Plaquemines LNG project and asked FERC’s permission to allow construction 24 hours per day, 7 days per week.

Not Being Neighborly

Dannie Bolden, whose family home in North Port St. Joe is less than a third of a mile from the site of Nopetro’s proposed Florida LNG export facility, said he and his neighbors weren’t told about the company’s proposal to build near the Black community. He first heard about the plan from Public Citizen, an environmental group that sued FERC over the commission’s decision to exempt the proposed facility from an environmental impact review.

While Nopetro didn’t communicate with residents, the company garnered the support of a state lawmaker, Rep. Jason Shoaf. Shoaf wrote FERC in 2021 in support of the company’s request to be exempt from environmental review — a process that encourages public comment. Shoaf failed to mention in that letter, which was written on his legislative letterhead, that his family owns the company contracted to supply Nopetro with gas, St. Joe Natural Gas Company.

“That’s a conflict of interest there. His family owns the right to the natural gas that comes into town,” Bolden said. “There’s no way in the world his family isn’t going to make money.”

The neighborhood where Bolden’s house is located is called “Millview Subdivision.” The name comes from a shuttered papermill that sat across the street, polluting the Black community for 60 years. “Now you’re saying to my kids and grandkids, ‘you’re going to have to suffer the same level of environmental abuse,’” Bolden said.

While Plaquemines LNG in Louisiana would be one of the largest export facilities on the Gulf Coast, Nopetro LNG would be one of the smallest. Because the facility plans to use trucks to transport LNG-filled shipping containers to a nearby dock —where the containers would be loaded onto ships headed to markets in the Caribbean, Central America, and South America — FERC determined the facility does not fall under its jurisdiction, and therefore does not require an environmental review.

By exempting the Nopetro facility, FERC has opened the doors for more communities to be blindsided by polluting facilities. “It’s an important case because it did create a loophole,” said Tyson Slocum, director of Public Citizen’s Energy Program. In January, Public Citizen filed its opening brief in the case against FERC’s decision.

Nopetro did not respond to requests for comment and has not responded to requests from other outlets. Slocum said it’s part of the company’s M.O. “They never make themselves available to journalists or members of the community. What do you think they’re going to do if they build this thing and a problem occurs?” he asked. “They’re not acting like good neighbors. That’s for sure.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts