Increased federal incentives for “carbon management” technologies are catalyzing a surge in proposed carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects in the United States, from the Gulf Coast to the Midwest to California. CCS proponents are touting their support of local community involvement in developing these sites. But residents say they are often left with empty promises.

“Meaningful engagement and support of local communities is essential,” Sally Benson, deputy director for energy and chief strategist for the energy transition at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, told attendees of the DC Forum on Carbon Capture and Storage held in May. The daylong conference, hosted by the pro-CCS think tank Global CCS Institute, in downtown Washington D.C., convened stakeholders from industry, governments, and nonprofits to discuss the current policy, financial, and societal landscape of carbon capture and storage (CCS).

Communities “should have a choice” when it comes to hosting an engineered carbon capture or carbon removal project, panel moderator Jessica Oglesby, senior communications lead for the Americas at the Global CCS Institute, said. “Ultimately this is up to the community,” she added. “This has to be a real choice for them, they need to have the option to say no but also the option and the incentives to say yes.”

Despite this rhetoric from CCS proponents about listening to local communities and giving them a chance to say no to projects, community groups opposing these projects claim this is not what’s happening on the ground. Excluded from the conference panels were people from the neighborhoods targeted for this massive industrial buildout. Developers of CCS projects generally don’t respect what communities actually want, Manuel Salgado, environmental justice research analyst with WE ACT for Environmental Justice, told DeSmog.

In response, Oglesby told DeSmog: “The highest levels of safety, environmental stewardship, and community engagement should be incorporated into all industrial and clean energy projects, including CCS.”

If statements “about communities having a real choice were true, then what we should see is that developers won’t pursue these projects in these areas.”

Manuel Salgado, environmental justice research analyst,

WE ACT for Environmental Justice

Yet amid mounting concerns over health and safety risks of carbon capture operations, and fears that CCS serves as a lifeline to the fossil fuel industry, DeSmog finds that communities in California, Iowa and Louisiana where CCS projects are proposed have limited to no meaningful engagement with developers or government officials. When residents express adamant opposition to these projects, developers continue to push their plans forward, in some cases resorting to legal action to counter public resistance.

“What we see with a lot of these CCS projects that are currently in development and where communities are engaging,” is residents telling the developers ‘no’, Salgado told DeSmog. If Oglesby’s statement about communities having a real choice were true, he said, “then what we should see is that developers won’t pursue these projects in these areas.”

Instead, project developers are forging ahead, eager to capitalize on billions of dollars in government subsidies supporting CCS deployment, despite the technology’s poor track record of underperforming and the significant regulatory gaps around CO2 pipelines, among other issues.

“I do feel that it’s a mad dash to push this forward. It’s not reliable,” Salgado said. “None of this feels as if it’s being done in an environmentally just way. It feels like we’re having this stuff just shoved down our throats.”

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) and the related carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies trap some of the carbon pollution emitted from industrial facilities; after chemically separating the carbon dioxide (CO2), the gas is compressed and transported, typically by pipeline, to another location where it is either used for other applications, in the case of CCUS, or injected deep underground for storage. The vast majority of currently operating projects in the U.S. use the captured carbon to drill for more oil in a process called enhanced oil recovery. Major oil and gas companies are some of the biggest backers of carbon capture technologies, and the worldwide advocacy group promoting them – the Global CCS Institute – counts oil majors like Chevron, ExxonMobil, BP, Shell, and TotalEnergies among its members.

While big polluters publicly tout CCS as a viable climate solution, internally they acknowledge that it perpetuates their extractive operations and is costly and inefficient. Many climate and environmental justice advocates say that CCS is an expensive boondoggle that entails risks at every stage of operation, from capture to transport to injection for supposedly permanent storage. At each of these stages, communities are battling against CCS companies to voice their opposition to becoming neighbors to these potentially dangerous operations.

McFarland, CA, Residents Challenge New CCS Facility

California’s Central Valley is an agricultural hotspot and also has some of the worst air quality in the U.S. A proposed new facility in the town of McFarland in Kern County plans to convert agricultural waste biomass into “renewable natural gas,” according to San Joaquin Renewables, the project developer, through a gasification process, using carbon capture technology to mitigate the carbon pollution. The captured CO2 would then be injected underground. San Joaquin Renewables claims the operation will result in decreased air pollution, because the biomass waste the procedure uses would otherwise have been openly burned, and the gas it produces would displace dirtier diesel fuel used in vehicles. But environmental advocates fear the project could actually diminish air quality in the Central Valley’s San Joaquin Valley even more.

“We’re talking about increasing air pollution for an overburdened community,” Genevieve Amsalem, research and policy director at Central California Environmental Justice Network, said during an August 15 public meeting on California’s S.B. 905, a new CCUS bill, hosted by several state agencies. Amsalem said the San Joaquin Renewables facility has said it plans to emit almost 70,000 tons of CO2 a year. “While they’re capturing some [carbon], it’s still a net polluter,” she said. The potential for CO2 leakage and interaction of the sequestered CO2 with geologic fault lines are among some of the other big concerns, she added.

A municipal document regarding preparation of a draft environmental impact report for the project affirms the possibility for these adverse impacts. The project location is “within a seismically active region and is located close to known faults,” the document says. Carbon dioxide could potentially be vented to the atmosphere, and the project is expected to produce air emissions during construction and operation. Additionally, the project is expected to generate “substantial haul truck traffic” to bring in the biomass waste, which implies more transportation emissions.

McFarland residents worry they will bear the brunt of the negative impacts of this new industrial project, and, as several of them told state officials during the August 15 meeting, they feel they weren’t sufficiently informed about the project by the developer and their local government.

“The problem is that we in these communities are pretty much forgotten,” Lupe Martinez, a resident of the neighboring town of Delano, said during the meeting. “We’re the ones who don’t know what’s really going on.”

Theolora Gonzalez, a more-than-20-year resident of McFarland, said many folks in the community are agricultural workers and the project would be “close to the jobs where we work” and close to people’s homes. She said the community feels it is “in danger” considering the potential for a CO2 leak, and she urged state officials during the meeting to come to the community and inform McFarland residents about the project. “No one has communicated anything about this project to us,” Gonzalez said.

San Joaquin Renewables did not respond to a request for comment.

Kern County, CA, Contemplates Carbon ‘Business Park’

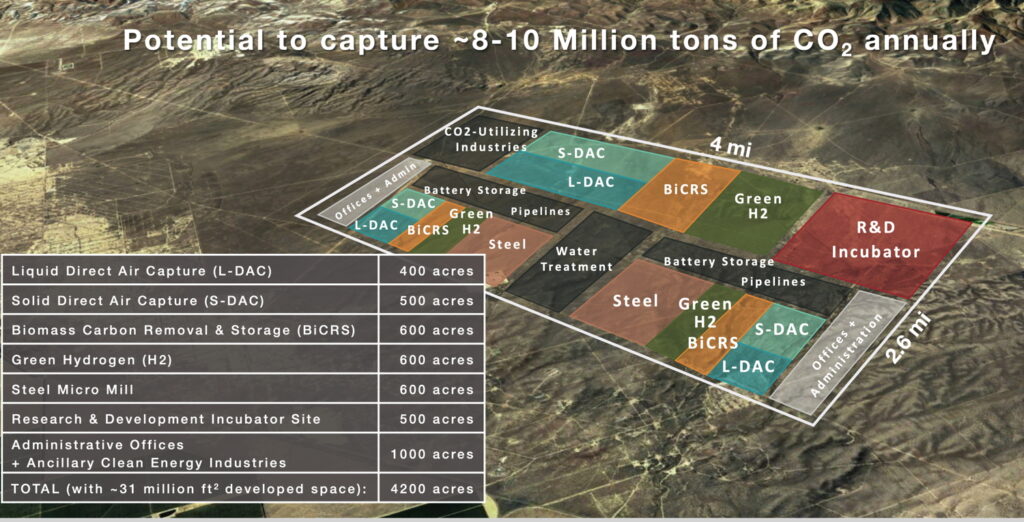

A similar deficit in community engagement is occurring with another proposed carbon capture project in Kern County, California. Called a Carbon Management Business Park, it is so far only a conceptual design for a 30 million square-foot “park” situated on 4,000 acres of repurposed farmland. It aims to host a variety of carbon capture operations, such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), direct air capture (DAC), a steel micro mill equipped with carbon capture, and “blue” hydrogen production. The Kern County Department of Planning and Natural Resources is leading the project, funded through a technical assistance grant from the U.S. Department of Energy for a pre-feasibility assessment.

According to Olivia Seideman, policy coordinator with the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, the county has done little to no actual community engagement in this early phase of the project. “The county is starting to move this project forward and they’re not talking to communities about it,” she told DeSmog. Even so, the general public sentiment towards the project idea is one of skepticism and concern. “We’ve had really overwhelming opposition to this being located anywhere in the county,” Seideman said.

If developers and government backers of CCS insist on ensuring “meaningful community engagement,” Seideman said, that would include “presenting information in a way that is honest about what the risks are.” And if there is community opposition, it means “not moving that project forward.”

The Kern County Department of Planning and Natural Resources did not respond to a request for comment.

Iowa Landowners Stand Up to Carbon Pipeline

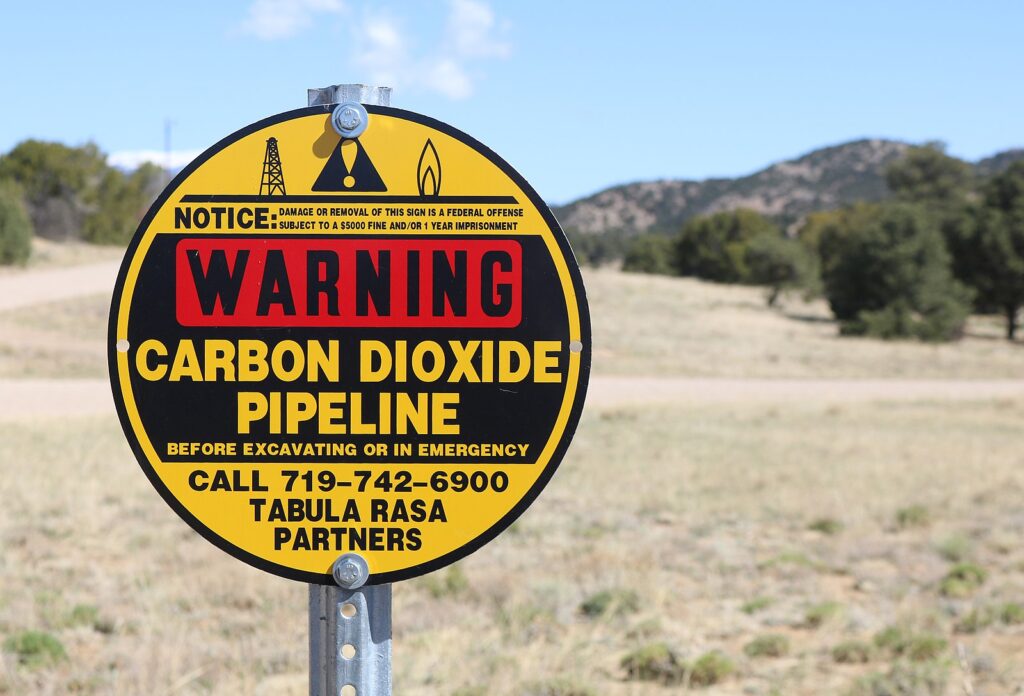

In Iowa, hundreds of landowners in the pathway of a planned CO2 pipeline are facing the prospect of having their land forcibly seized through a legal process called eminent domain. While this procedure is sometimes used to build gas pipelines and other infrastructure, it has not been widely applied to pipelines transporting CO2 because the existing carbon pipeline network in the U.S., roughly 5,000 miles, is relatively limited and spans sparsely populated areas. But as more and more carbon capture projects get underway, spurred by significant federal subsidies to support the CCS buildout, new pipelines would need to be built to carry the captured pollutant from the emitting source to the underground storage site.

Iowa is currently on the frontline of this early CO2 pipeline buildout, with several proposed lines – all tied to carbon capture at Midwest ethanol and fertilizer plants – planned to cross the state. In October the developer of one of the proposed pipelines, Navigator CO2 Ventures, canceled its project after facing staunch grassroots opposition from farmers, landowners, and environmentalists. South Dakota regulators also denied its permit application.

The project furthest along procedurally is a 2,000-mile pipeline, nearly 700 miles of it in Iowa, developed by CCS firm Summit Carbon Solutions. In recent months North and South Dakota regulators blocked permits for the project. In Iowa, the company initially filed its permit application with the Iowa Utilities Board (IUB) in early 2022. It claims to have widespread support throughout the state with landowners voluntarily signing easement agreements covering 75 percent of the route across 29 Iowa counties, according to Sabrina Zenor, director of corporate communications for Summit.

But many of these landowners were not eager to sign over their land and some said they felt coerced into it, according to Jess Mazour with the Iowa Sierra Club, one of the main groups organizing opposition to the Iowa CO2 pipelines. She said Summit has been “bribing, harassing, threatening, [and] intimidating people” and noted with the analogy, “Just because somebody robbed you at gunpoint doesn’t mean they gave you their wallet voluntarily.”

Several landowners have testified that they felt pressured during the negotiations with company agents threatening eminent domain. When DeSmog pointed this out, Zenor responded: “Any Summit team member who is found to have pressured landowners around the possibility of eminent domain being used will be disciplined and, if such behavior continues, terminated by the company.”

Landowners who refused to sign over their land to Summit could still have their private property seized through eminent domain. Summit has initiated legal proceedings around surveyor access while state regulators review its permit application. “I’m being sued for not letting a survey crew on [my land],” Dan Walh, an impacted Iowa landowner and farmer said during an online telepresser held in June. Wahl and other landowners in his position said that not only is the pipeline company showing disrespect and aggression, but it is also being dishonest about the project’s risks.

“At one point early on [Summit] said it’s just like the bubbles in your [soda] pop,” Sherri Webb, an impacted landowner in Shelby County whose farm has been in her family for over a century, told DeSmog. Contrary to this assertion, CO2 transported through commercial pipelines is considered a hazardous substance; in the event of a pipeline rupture, it could poison entire communities in its path.

Webb said that if you own land, and especially if you’ve owned it as long as her family has, you absolutely should have the right to say no to a commercial developer. But trying to stand up to a deep-pocketed corporation like Summit is not really a fair fight, she added. “I think they are running the show because they have so much money,” Webb told DeSmog. “We feel like the deck is really stacked against us.”

The IUB’s public hearings regarding Summit’s permit application began in August, about two months sooner than was initially scheduled. After two new members joined the Board in May, the Board announced in June its decision to fast-track the hearing schedule. The Sierra Club’s Mazour said this accelerated timeline left landowners in a “mad rush” to prepare, arguing the IUB’s move was a “violation of due process rights.” Mazour suspected that Summit, which holds considerable political sway in the state, including the support of Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds (R) (who appoints members to the IUB), was the driver behind the decision to fast-track the hearing schedule.

“They have so much power that they know they can get what they want,” Mazour said, “so they just shove their way through.”

Proposed site near Lake Maurepas for Air Products’ carbon injection operation. Credit: Julie Dermansky

Locals Oppose Using a Lake as a CO2 Disposal Site

“It’s unproven science,” Bill Whittington, a member of a local group called the Lake Maurepas Preservation Society, said during an August 2 public hearing in Baton Rouge, referring to the claim that once injected underground, the carbon will be sequestered there permanently. “Y’all are gonna destroy our lake.”

At about 93 square miles in size and 10 feet deep, Lake Maurepas is located on the western side of the larger Lake Pontchartrain. It is a shallow estuary shrimp and crabs migrate to from the Gulf of Mexico during winters. The lake provides both seafood and storm surge protection. But the carbon injection operation threatens all of that, community members fear.

When Air Products first announced the hydrogen project in 2021, residents were still recovering from Hurricane Ida, and many did not yet have their power restored. That made the project’s virtual meetings held via Zoom inaccessible, and there was no mention during the project announcement of the plan to use the lake as the storage site for the captured CO2.

“Even as public officials in the parishes, no one knew,” Tangipahoa Parish Council member Kim Coates said. “So there was very little transparency, or no transparency initially.”

Coates and other local parish leaders were dismayed that the state did not inform them of the plan to use Lake Maurepas for the project, and they are doing what they can to push back. Livingston Parish took the step of passing a 12-month moratorium on Class V injection wells in October 2022, but the moratorium was dropped after Air Products sued the Parish and a federal judge ruled in the corporation’s favor. Coates said Tangipahoa Parish discussed passing a moratorium as well, but their attorney advised against it. “We didn’t do a moratorium because we knew we would lose because we would get sued,” she said.

Tangipahoa Parish Council member Kim Coates, center, at a public meeting in Ponchatoula on October 17, 2022. Credit: Julie Dermansky

Her parish and others neighboring the lake also passed resolutions opposing the Air Products project and sent them to their state representatives and senators. Coates said several of those representatives tried to pass bills this past session aimed at stopping or restricting the project, “and they were defeated because Air Products hired over 25 lobbyists to fight it.”

Despite overwhelming opposition from local communities, Air Products is pushing forward with its plan to inject CO2 under Lake Maurepas. It has completed seismic testing and is now drilling test wells. Air Products says it aims to have the project operational by 2026.

But local residents and officials are not giving up the fight. “When you have multiple parishes, multiple municipalities, hundreds of people that have attended meetings and opposed it,” Coates said, “[Air Products] shouldn’t just force it on them.”

Air Products did not respond to a request for comment.

A Community-Centered Approach in CA

In California’s southern San Joaquin Valley, an organization called Carbon180, a nonprofit that focuses on advancing carbon removal in an equitable manner, and other partners are exploring the potential to build what they call a community-led direct air capture (DAC) hub. If the hub gets built, Carbon180’s project could illustrate what actual meaningful engagement with communities looks like in practice when developing carbon capture or carbon removal projects.

Unlike other carbon capture projects in the works, the community’s right to say no will be an important piece of the engagement process, according to those leading the project.

“Communities deserve the right to determine for themselves what they house and live with day in and day out,” Vanessa Suarez, managing environmental justice advisor at Carbon180 – said in an interview. “It’s really important to us that our project includes the ability for them to tell us ‘no.’”

Direct air capture involves building machines that suck CO2 out of the atmosphere, a process that is very energy-intensive and costly. The only DAC facility currently operating at a commercial scale anywhere in the world is in Iceland, though more are under development including several that Occidental Petroleum is building in the U.S. The Houston-based oil and gas company is embracing direct air capture as a way to perpetuate its oil extracting business model. In August the US Department of Energy (DOE) announced that an Occidental subsidiary was selected as one of two recipients of federal funds to develop DAC hubs.

It is fair to be skeptical of this nascent technology especially in the hands of fossil fuel companies, Suarez said. “DAC is being used by oil and gas companies to greenwash oil and repeat the past harms of that industry,” she told DeSmog, acknowledging there are “real, potential risks associated with DAC processes.” Carbon180 and its partners have formed a coalition called the Community Alliance for Direct Air Capture (CALDAC), supported with $3 million in DOE funding, and, according to Suarez, they “hope to prove to Central Valley communities that DAC can materialize in a different, non-industry-driven way.”

But, Suarez emphasized, “we are not here to convince anyone.” She said if community members and stakeholders decide that a DAC hub “will not serve their wants and needs after a nine-month go/no-go decision point, the project will end.”

Carbon Engineering pilot plant in Squamish, B.C., featuring Direct Air Capture (DAC) technology that captures carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere

Credit: Stephen Hui, Pembina Institute/Flickr

“We believe that the only way to scale good carbon removal is to prioritize the rights, wants, and needs of communities, including their right to self-determination – even if that means they don’t want these projects in their neighborhoods,” Suarez said.

Genuine community engagement, environmental justice advocates emphasize, means listening to the concerns of the locally impacted community and actually addressing those concerns.

“It’s not about having a performative hearing,” said Salgadao of WE ACT for Environmental Justice. “If that engagement turns out to be communities telling you they don’t want CCS, then listen to them and take those concerns seriously and abide by them. It doesn’t mean doing something that’s incredibly performative, and then, in spite of that community’s concerns, proceeding with your plans regardless of what they want.”

Victoria Bogdan Tejeda, an attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity, agrees with Salgadao that CCS proponents aren’t actually listening to communities’ desires, noting that public opposition to risky and unproven carbon capture projects is mounting.

“The more people learn about CCS and its dangers and risks, they’re understanding that these are not projects they want, these are harms that can’t just be mitigated away,” she said. “These projects should not get built in the first place.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts