This story was updated February 7, 2024 to include comments from the Norwegian Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries and RAMPAO.

Producers in Norway, the world’s top supplier of farmed salmon, are pushing up to four million people in West Africa into food insecurity and depriving them of critical nutrients, according to a new report.

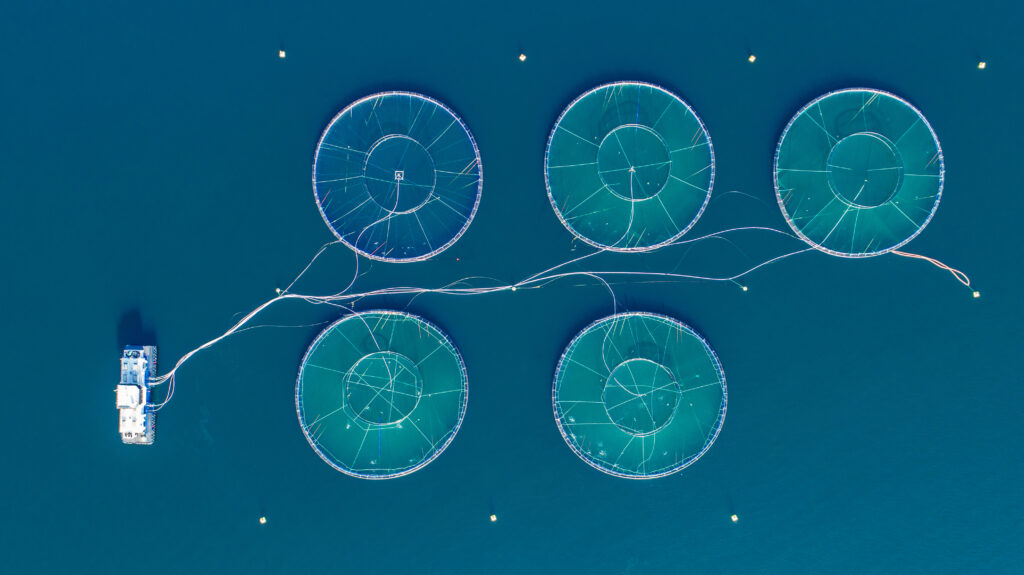

Published by food and farming campaign group Feedback Global, the research states that major farmed fish and aquafeed producers – including European transnational companies Mowi, BioMar, Cargill, and Skretting – are between them extracting nearly two million tonnes of whole, wild fish annually from the world’s oceans, according to 2020 data.

The majority of these small, highly nutritious fish are being turned into fish oil, a key ingredient in salmon aquaculture feed, as well as fishmeal – the product of grinding up whole fish or fish byproducts into a flour used in aquafeed and feed for livestock.

While still a relatively small player globally, the fishmeal and fish oil industry in West Africa has grown over the past decade amid a backdrop of hunger and nutrient deficiency. In sub-Saharan Africa, 62 percent of children under five lack essential micronutrients – such as iron, zinc, and vitamin A – and consume just 38 percent of their recommended seafood intake.

Feedback’s report comes as the Financial Times published an investigation tracing the supply chain of Norwegian powerhouse Mowi, the world’s biggest salmon farmer, to Mauritania, where catches of sardinella, a key fish in West African diets, have declined steeply since the Norwegian salmon industry began sourcing from the region.

Yves Reichling, a project manager of Feedback’s West Africa programme, said: “For an industry that is so vocal about feeding the world, it certainly is quiet about the fact that it uses millions of tonnes of wild marine resources from around the globe, including from food insecure regions such as West Africa, to feed to its farmed salmon.”

The report also claims that Norway’s embrace of the industrial aquaculture industry undermines its international development policy to increase global food security, including in sub-Saharan Africa, in a “startling lack of policy coherence”.

Deputy Minister Even Tronstad Sagebakken, of the Norwegian Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries, told DeSmog that the Norwegian government “wants to ensure sustainable feed for farmed salmon and livestock”.

He added: “It is important ensure good control over raw materials that go into the feed, and that we explore alternative sources. Increased use of local and more sustainable raw materials for fish feed is important to reduce the pressure on the climate and environment, and for a green transition in Norwegian food production.”

Mowi, Skretting, Cargill and BioMar did not respond to requests for comment.

Taking the ‘fish of the people’ to ‘feed the world‘

Feedback Global’s report accuses the Norwegian salmon industry of “nutrient colonialism”. That’s because it’s directly competing with people in the region – who eat these pelagic fish and rely on them for employment – to produce salmon for wealthier consumers elsewhere.

This includes the UK, where multiple supermarkets stock salmon supplied by Mowi, which sources fish oil from Mauritania for its salmon feed.

Dubbed the “fish of the people”, small pelagic fish (also known as “forage fish”) have historically been an affordable and nutritious source of food in West Africa. In Senegal and The Gambia, they typically provided an average of 65 percent of these communities’ animal protein.

Forage fish are also chock-full of critical micronutrients such as iron, calcium, vitamin A, and omega-3 fatty acids, all of which are especially important for children in their first thousand days of life, and for pregnant women and nursing mothers.

It’s that same nutrient density that makes pelagic, or open-ocean, fish a target for aquafeed and farmed salmon producers.

Naturally carnivorous, salmon reared on farms require feed made up of about 30 percent fishmeal and fish oil to replicate their diets in the wild and remain healthy.

With salmon production booming, farmed salmon now consume 44 percent of the world’s fish oil, according to calculations made by DeSmog (based on a 2022 report published by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization and a 2022 study). Despite this heavy reliance on wild-caught fish, salmon only makes up 4.5 percent of seafood produced by the global aquaculture industry.

While salmon companies claim their products “feed the world”, studies show that high value carnivorous fish like salmon will remain out of reach for the world’s poorest consumers for the foreseeable future, and that the vast majority of salmon is eaten by people in wealthy countries.

A 2022 study found that in the majority of sub-Saharan countries, redirecting just 20 percent of pelagic fish caught in the region back to human consumption would allow every child living near water who is between six months and four years of age to meet their daily recommended intake of fish.

Some of the species sourced by salmon- and feed-producing companies off the coast of West Africa are classified as overexploited by the the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), which recommended in 2016 that fishing pressure on these species be halved in the North East Atlantic. Despite this, exports of fishmeal and fish oil have increased from West Africa by more than fifty percent since 2016, with fish oil exports having more than doubled.

Marie Suzanna Traoré, the executive secretary of RAMPAO (the regional network of marine protected areas (MPAs) in West Africa), told DeSmog that in the last decade, some marine protected areas have dealt with “often unfair competition between industrial boats and artisanal canoes [which] has led to a scarcity of fish, in particular, the small pelagic fish stocks, as a result of the overexploitation of fish resources in the waters of the western coasts of West Africa”.

Mowi told the Financial Times that it would be “in best case misleading” to link its sourcing to declining fish stocks. Mowi, BioMar, Skretting, Cargill, and UK supermarket Asda also told the outlet that they source their Mauritanian ingredients from factories recognised by industry certification body MarinTrust as working to improve the fishery.

‘Wasteful’ farming and obscure supply chains

The report also claims that turning high-quality fish that humans might otherwise eat into salmon feed is “incredibly wasteful”.

Karen Luyckx, a researcher for Feedback and co-author of a 2022 study on maximising nutrients from both wild-caught and farmed fish, said that if people were to eat even half of the fish currently being turned into fish oil for salmon, the food system could deliver “equal or better calcium, iron, vitamin D, [and omega-3 fatty acids] EPA and DHA” to consumers.

“This means that nearly one million tonnes of fish currently turned into fish oil fed to salmon could instead be left to support ocean ecosystems and food security without changing the key micronutrients currently supplied to wealthy consumers via salmon.”

Feedback’s report also points out the industry’s lack of supply chain transparency, particularly the absence of standardised, comparable data. Few aquafeed companies share information about which individual factories they source from in West Africa, making it difficult to trace the exact environmental and socioeconomic impact of their operations, despite evidence of harm.

“The fishmeal and fish oil factories in Mauritania and Senegal have a real impact on our activity,” explained a fisher from Saint Louis, Senegal in a recent report by Partner Africa, an NGO that audits the labour conditions of workers on the continent. “They need a lot of small pelagic [fish], and now, with the scarcity of fish, the fishermen catch the juveniles. If the situation does not change, there will be no more fish in these areas within a few years.”

Feedback’s Luyckx suggested that the aquaculture industry should focus on raising species that require “no or only minimal amounts of marine ingredients in their feed”. She believes only by-products should be turned into feed for carnivorous species like salmon and shrimp, not whole, fresh fish.

She added that a food system that combines of whole pelagic fish and “unfed or feed-efficient aquaculture species” to feed people could “deliver vastly superior quantity and quality of food globally,” pointing to bivalves as one such “food of the future” that doesn’t rely on feed but still packs a nutritional punch.

To Feedback’s Reichling, the whole situation is “absurd” for those in West Africa. “Artisanal fishing communities should not have to struggle to make a living and see their source of income and food stolen by profit-hungry corporations,” he said.

Learn more about the global aquaculture industry in DeSmog’s Industrial Aquaculture Database, where we document major players’ stance on sustainability, information on fish feed supply chains and record of lobbying.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts