This story is the second part of a DeSmog series on carbon capture and was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe, and in partnership with Follow the Money. To read the first story, click here.

Previous versions of this story contained errors in relation to the potential cost to the Dutch taxpayer of the Porthos project. The story has been corrected to draw a clearer distinction between subsidies and project finance, and include additional context from the Dutch government and Court of Audit.

One Saturday in April, Dutch engineers manoeuvred a giant drill into position in the reclaimed, industrial extension of the Port of Rotterdam, and began boring a hole under the seawall. Nearby, sections of metal pipe waited to be lowered into the breach.

The operation was a step forward for Europe’s most advanced scheme to capture carbon dioxide (CO2) from industry, then bury the planet-heating gas under the North Sea.

After years of delay, a joint venture known as Porthos, an acronym for Port of Rotterdam CO2 Transport Hub and Offshore Storage, is due to begin operating in 2026. It’s a 1.3-billion-euro joint venture between state-owned gas companies Energie Beheer Nederland (EBN) and Gasunie, and the Port of Rotterdam Authority. The CEOs of these organisations are due to join Sophie Hermans, the Netherlands’ minister of climate policy and green growth, and senior European Union officials, for a ceremony on Monday to toast the start of construction work at the site.

At full capacity, Porthos is expected to handle 2.5 million tonnes of CO2 captured annually from facilities operated by its four dedicated customers: Shell, ExxonMobil, and the hydrogen producers Air Liquide and Air Products. That total is equivalent to roughly 10 percent of the port’s emissions, and 1.5 percent of the Netherlands’ current CO2 output. Once captured, the gas will be pumped under the North Sea throughout a 15-year period, or until the storage space reaches a maximum estimated capacity of 37.5 million tonnes.

The key ingredient: A government pledge of up to 2.1 billion euros in subsidies.

Porthos relies on a technology known as carbon capture and storage, or CCS, which uses a chemical process to capture some of the CO2 that spews from a customer’s industrial chimneys. This trapped gas is then condensed and pumped through pipelines to underground storage sites, such as certain kinds of geological formations, or disused oil and gas wells.

But what sounds good in theory doesn’t necessarily translate into practice: Many flagship CCS projects have been plagued by cost overruns, delays and missed capture targets — fuelling scepticism among environmental groups, and energy and financial analysts.

Nevertheless, the backers of Porthos, and its much larger sister project Aramis — also being developed by EBN and Gasunie, along with Shell and French oil giant TotalEnergies — see them as the first nodes in a planned network of pan-European CCS infrastructure. The aim is to eventually funnel CO2 captured in the industrial heartlands of Germany, as well as throughout the Netherlands, to hundreds of storage sites under the seabed.

To its critics, however, Porthos is emblematic of the way oil and gas companies are securing subsidies for CCS schemes that present an appearance of climate action — but are never likely to attain the massive scale needed to make a dent in global emissions.

As Europe’s flagship project, Porthos is emerging as a litmus test for a critical question in the fight against climate change: Will carbon capture actually help reduce the emissions fuelling the crisis? Or will government backing for these technologies instead serve to preserve the fossil fuel business models that caused it?

Sections of pipe for the Porthos CO2 pipeline, intended to take captured carbon emissions and inject them under the North Sea, await burial at the Port of Rotterdam. Credit: Michael Buchsbaum.

Ambitious Plans

With intensifying heatwaves, floods and fires underscoring the threat the climate crisis poses to Europe, the EU has agreed to slash its carbon emissions to net zero by 2050, with an interim target of a 90-percent reduction relative to 1990 levels by 2040. Given the scale of that challenge, and in line with lobbying by the fossil fuel industry, policy-makers have assumed a major role for carbon capture projects in cleaning up industry.

“Reducing emissions is not enough,” reads a European Commission website on CCS. “To achieve our climate ambitions, we will also need to capture, utilise and store carbon.”

Climate campaigners argue, however, that the technology has secured official backing in large part because it helps governments persuade voters they are taking climate action, while stopping short of the kind of rapid, fundamental transformation of economies needed to end the use of fossil fuels.

In May, the EU adopted the Net Zero Industry Act, obligating oil and gas producers to develop 50 million tonnes of annual CO2 storage capacity across the continent by 2030 — roughly equivalent to today’s global total. More ambitiously, the act targets approximately 280 million tonnes of annual CO2 storage capacity by 2040, increasing to a staggering 450 million tonnes by 2050.

Environmental groups such as E3G, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis and European Environmental Bureau doubt such targets are feasible, given the thousands of kilometres of pipelines that would have to be built, and the dozens of projects that would have to be designed. A lack of technical and geological know-how combined with potential local opposition could also slow fossil fuel companies’ plans.

“The industry needs to commit to genuinely helping the world meet its energy needs and climate goals —which means letting go of the illusion that implausibly large amounts of carbon capture are the solution,” said Fatih Birol, executive director of the Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA), in the introduction to a report on clean energy transitions for oil companies published in November.

Despite the oil industry often citing scenarios from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that include significant deployments of CCS, the U.N.-backed body also considers the technology the least efficient, and one of the most expensive, climate tools. In their Sixth Assessment report, the IPCC’s scientists wrote that “even if implemented at its full potential, CCS will account for only 2,4% of the world’s carbon mitigation by 2030 due to its low effectiveness and high cost.”

And Europe is nowhere near close to meeting its carbon capture targets. Today, only 2.7 million tonnes of CO2 is being captured annually across the continent, including in Norway and Iceland, according to the IEA. Porthos’ backers are therefore hailing the project as a crucial step towards fulfilling the continent’s decarbonisation plans — starting with its largest port.

“If we want to reach our climate target, we will need CCS,” Willemien Terpstra, CEO of Gasunie, told DeSmog.

Still, even backers of the technology acknowledge that deployment is lagging. To meet the EU’s target of capturing 280 million tonnes of CO2 annually by 2040 would require 651 projects, said Chris Davies, director of industry group CCS Europe. Each would have to capture more than 400,000 tonnes per year, he told DeSmog.

To date, 50 years after the first CCS projects were started in a Texas oilfield, only about 40 projects are operating globally, with the combined potential to capture just over 50 million tonnes of CO2 per year. However, almost 80 per cent of the CO2 being captured is injected underground to pump more oil — which when refined and burned, adds more CO2 into the atmosphere.

While there is no estimate as to how long it would take to construct hundreds of projects, it is clear that time is running out, Davies said.

Capturing this amount by 2040 requires that construction on all these projects begin no later than early 2038: “So we have less than 5,000 days,” said Davies.

Since Porthos’ backers took a final investment decision last year, no other CCS project “has been given the green light to put a shovel in the ground”, he added.

Cleaning up the Quayside

With docks and quays stretching from its old town centre to the ocean over 40 kilometres away, the Port of Rotterdam covers an area almost twice the size of Manhattan, and handles nearly 440 million tonnes of freight each year, roughly the equivalent of more than 1,200 Empire State Buildings stacked on top of each other.

Not only is Rotterdam a massive cargo port, it’s also one of the largest hubs for energy in Europe, including oil. Counting oil, coal, and liquefied natural gas, the port boasts that some 13 per cent of all the energy used throughout Europe passes through it.

Most of the oil is destined for one of the port’s four refineries, including the giant Shell Pernis facility, as well as sites run by BP and Exxon. (Reducing emissions from the refineries is one of Porthos’ key aims).

All this activity generates tremendous amounts of carbon pollution: The port emitted 20.3 million tonnes of CO2 in 2023.

The port intends to slash its emissions by 55 per cent by 2030, then achieve climate neutrality by 2050.

The port argues that it can reduce its emissions to its target of 9.3 million tonnes by 2030 by:

- Storing up to 5.8 million tonnes of emissions annually by the end of the decade through its Porthos and Aramis projects

- Reducing emissions by another 5.7 million tonnes by shutting down, as legally required, its remaining coal-fired power plants by 2030, building on savings made by previous coal plant closures

- Greening its operations with electrification, and “green” hydrogen made with wind and solar

“Porthos and Aramis by far contribute the most to the Netherlands’ CO2 reduction targets…the Dutch goals cannot be met without those projects,” Hans Coenen, Executive Board member of energy company Gasunie, told Follow the Money, the Dutch investigative journalism platform that co-published this story with DeSmog.

Taxpayers Foot the Bill?

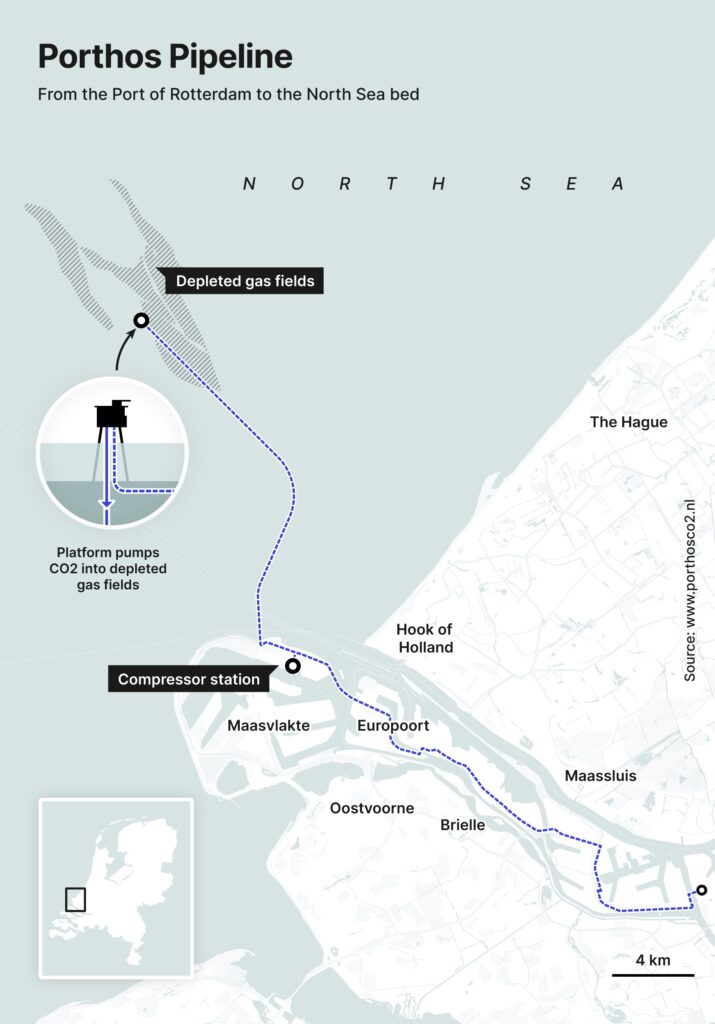

Crucially, Porthos will not be capturing any CO2 itself, instead handling and storing CO2 captured by Shell, Exxon, Air Liquide and Air Products. Porthos itself consists of a new 30-kilometre pipeline system leading to a compression station. From there, CO2 will be pumped to a repurposed gas drilling platform 20 kilometres offshore, and injected into a depleting gas field for final storage.

To ensure emissions are captured, in 2021, the Dutch government allocated Shell, Exxon, Air Liquide and Air Products up to a combined 2.1 billion euros via its SDE++ scheme to subsidise company decarbonisation projects.

As it stands, under a long-running scheme known as the European Emissions Trading System (ETS), these companies are already required to buy credits for each tonne of CO2 they emit.

Although the credits currently trade at just under 69 euros per tonne, the price could almost triple by 2035, according to BloombergNEF.

By disposing of some of their emissions via Porthos, its customers save money by having to purchase fewer credits.

But, if buying ETS “emission certificates” is cheaper for them than storing the gas via Porthos, then the Dutch government will make up the cost difference using up to 2.1 billion euros allocated under the SDE++ scheme. (The Dutch government has said it is confident that the actual costs to the state will be significantly lower, since payouts will depend on the price of emissions certificates and project costs).

This means that whatever happens, the companies face limited risk, and potentially large savings, if they capture emitted CO2 instead.

The port says this arrangement enables the companies “to cut back their carbon emissions without weakening their respective competitive positions.”

Alternatively, without state support, “Porthos would not have gotten off the ground and this project would not have been able to contribute to achieving the climate objectives,” Ellen Ehmen, Exxon’s community relations manager in the Netherlands, told DeSmog.

In March, the Netherlands Court of Audit found in a report that Porthos represented an effective approach to helping to meet Dutch climate targets, concluding that the government would not have to pay out any SDE++ subsidies, under base case assumptions for the likely development of the carbon market.

But the report warned that the way the project had been structured meant that the state has assumed a disproportionate level of risk relative to industry.

Coenen, of Gasunie, says that he wasn’t surprised by these findings: “We decided deliberately to accept a low return on investment on Porthos, because we find it important to kickstart the project.”

Experimental Projects

Many climate advocacy groups, academics and policy experts have long warned of the dangers of relying on carbon capture projects, arguing that they provide fossil fuel companies with a justification for pumping ever more oil and gas.

Seeking to allay those fears, the European Commission advised in February that carbon capture should only be used in sectors where industry argues that emissions are particularly difficult or costly to cut, for example steel, cement, aluminium, chemicals and waste-to-energy.

But Porthos’ customers are using carbon capture for very different purposes: they’re either developing never-before attempted “low-carbon” projects that may be deployed at some point in future, or capturing a portion of the emissions now being generated by producing hydrogen used in the port’s oil refineries.

Shell, the first company to agree to partner with Porthos, is slated to become the project’s largest single customer, having committed to deliver 1.2 million tonnes of CO2 annually — captured mainly from its sprawling Pernis refinery complex, Rotterdam’s biggest. Shell also pledged to capture 820,000 tonnes a year from its to-be constructed biofuels facility, which is designed to produce so-called sustainable aviation fuel, as well as renewable diesel made from waste oil.

This so-called HEFA (hydroprocessed esters and fatty acids) plant is “essentially where the Porthos project starts,” said Nico van Dooren, director new business, hydrogen infrastructure, transport and storage with the Port of Rotterdam, during a media tour of the Porthos project in May.

Carbon capture “is the low hanging fruit,” Shell spokesperson Marc Potma said during the tour. “We have always said we believe in CCS for the future, but it’s never going to be the only answer. One must also invest in renewable sources, which is why we invested in the biofuels factory.”

Fellow oil and gas major Exxon’s CCS plans at Porthos are also highly experimental. Exxon says it plans to capture CO2 from a pilot project to test a new technology known as carbonate fuel cells — which the company says could help capture CO2 from industry more efficiently than existing methods, while also generating electricity, heat and hydrogen. This technology has never been proved at scale.

Also the recipient of EU funds, Exxon’s pilot plant is expected to be constructed in 2025, and start operations in 2026. Unlike Shell, Exxon has not announced any plans to use Porthos to capture emissions from its own oil refinery at the port.

Porthos’ two other customers are both large-scale hydrogen manufacturers who are producing the gas for use in oil refining — today one of hydrogen’s main uses.

As part of its participation in Porthos, U.S.-based Air Products announced in November it would build a carbon capture project at its existing hydrogen production facility in Rotterdam. Billed as the largest such facility in Europe, the project aims to help the company more than halve its CO2 emissions within the Port, while supplying most of the resulting hydrogen (known as “blue” hydrogen since some of the CO2 generated during the production process will be captured) for use in the nearby Exxon refinery.

Just weeks later, in December 2023, French rival Air Liquide announced it would also retrofit the company’s existing hydrogen facility in Rotterdam with carbon capture, using a proprietary technology that has only been tested at a smaller facility in Port-Jérôme-sur-Seine, France.

Aramis Following Porthos

As workers dig trenches and bury Porthos’ pipelines around Rotterdam’s port, Shell and TotalEnergies — together with Gasunie and EBN — are working on the larger Aramis project. They want to funnel and bury CO2 emissions captured in Germany, Europe’s biggest emitter, and send them via a yet-to-be-built pipeline project known as the Delta Rhine Corridor.

By 2028, two years after Porthos is due to come online, the first phase of Aramis is scheduled to transport up to 7.5 million tonnes of CO2 for storage — also thanks in part to EU subsidies.

To connect Rotterdam to Belgium, Gasunie is also working on a so-called Delta Schelde Corridor. “It’s going to be one interconnected system in order to help our industry,” Gasunie’s Coenen told Follow the Money.

Signalling EU support, in mid-June, the European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency, or CINEA, awarded Aramis 124 million euros in subsidies under the CEF Energy fund. CINEA also granted 33 million euros in funds to another planned Rotterdam CCS hub, known as CO2next.

The bigger question, however, is whether these projects will be completed on time.

At the end of June, the then Dutch Minister of economic affairs and climate policy, Rob Jetten, told parliament that the Delta Rhine Corridor pipelines wouldn’t be completed before 2032 — dealing a blow to the pace of CCS development.

In early July, Shell “temporarily” paused construction of its crucial biofuels plant that is supposed to produce 820,000 tonnes a year. Shell now says production will only begin “towards the end of the decade,” said Shell spokesperson Wendel Broere.

A Temporary Solution?

Regardless of when they come online, Porthos and the other planned Dutch CCS projects are generally presented as temporary solutions giving industry time to wean itself off fossil fuels — but how long that transformation will take remains unclear.

With billions of euros being invested, “you just have to count on a few decades,” Gasunie’s Coenen said.

Even as Porthos, Aramis and similar projects inch forward, further questions loom: Who will pay the enormous cost of rolling out the network of carbon capture facilities and pipelines needed to ferry CO2 from Europe’s industry to disposal sites in the North Sea via Rotterdam? And can such a project be completed in anything like the timeline demanded by the EU’s carbon capture targets?

Another unknown is how investing in these and other CCS projects will lead to a reduction in overall emissions — particularly since so many planned CCS projects involve building new fossil fuel infrastructure, such as gas-fired power stations or blue hydrogen facilities, rather than retrofitting existing industries. It is also unclear how subsidising industries to adopt CCS will compel fossil fuel companies to accelerate the shift to renewables.

Berte Simons, business unit director of CO2 transport and storage systems at EBN, the Dutch state-owned gas company, said that companies not only have to start capturing emissions, but stop producing them.

“There needs to be an end date to using CCS from fossil sources,” she said. “The sooner [fossil fuel companies] are able to green their portfolio, the quicker they can start with that, the better.”

For many climate advocates, the danger is that carbon capture will simply prolong business as usual — while soaking up billions of euros in subsidies.

Relying on CCS “isn’t a sensible climate mitigation strategy or even a proper carbon management strategy,” Lili Fuhr, deputy director of the Washington D.C.-based Center for International Environmental Law’s Climate and Energy Program, told DeSmog. “It’s really an escape hatch for an industry with its back against the wall faced with an energy transition that is gaining support and is becoming a reality because renewable energies are so cheap.”

Additional reporting by Birte Schohaus.

This story was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts