In the fall of 2017, the American Petroleum Institute (API) sponsored a workshop for Pennsylvania Girl Scouts, featuring “activities that mimicked work in the energy industry.” Each scout left with a “coveted patch and a greater understanding of natural gas and oil,” API’s CEO Jack Gerard reported in an “Executive Update” email — one of the API member companies that co-funded the event.

What America’s most powerful oil lobby likely did not tell the Girl Scouts, however, was that API had hosted the seminar as part of its mission to cultivate “nontraditional local allies,” described by Gerard as some of the “best and most influential voices with targeted policymakers on industry issues.”

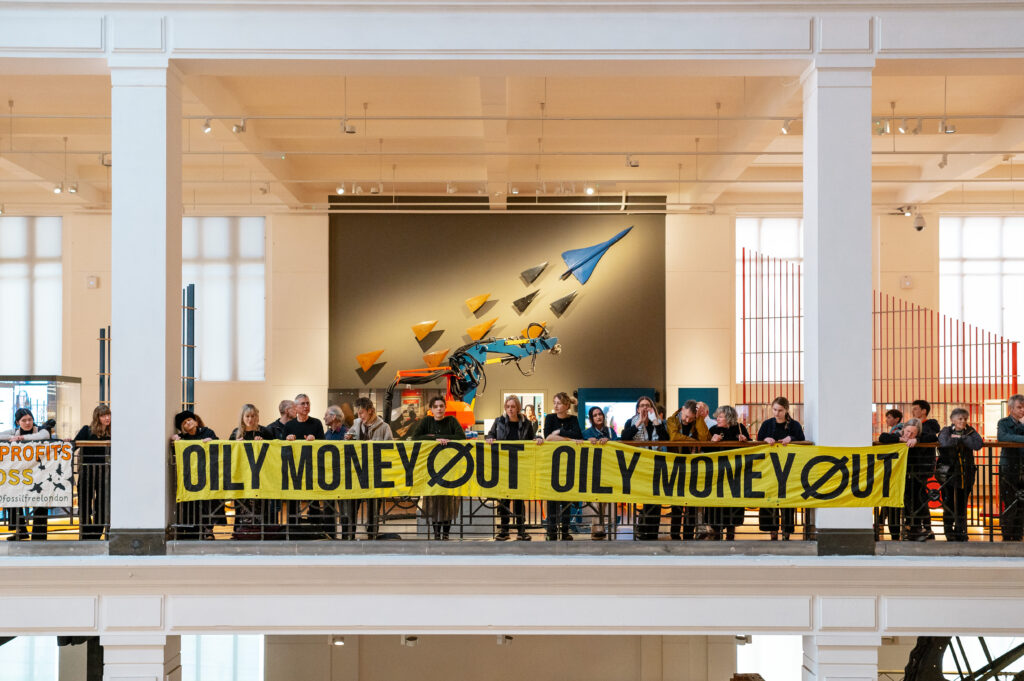

For years, campaigners have warned cultural institutions against accepting oil money, arguing that sponsorships are a key weapon in the public relations arsenal the industry deploys to thwart climate action.

Dozens of documents uncovered by a U.S. Congressional investigation appear to confirm those suspicions – demonstrating that API and oil giants BP, Shell, and Chevron have used sponsorships to allay public concerns over their role in the climate crisis while simultaneously lobbying against policies aimed at tackling it.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts

DeSmog discovered the documents by combing through thousands of internal memos, emails, and other communications subpoenaed by the Congressional investigation into climate disinformation by the fossil fuel industry, which published its report last year.

Dated between 2015 and 2021, the documents show oil companies funding sponsorship programs meant not only to enhance their reputations as socially responsible corporations, but also to ward off anti-climate change regulations that might undercut their oil and gas business.

The documents (which can be viewed online) reveal how BP America communications staff were instructed to use the company’s sponsorships to protect BP from “external threats” such as “the policy and politics of climate change,” how Chevron leveraged its sponsorship programs to “advance business objectives” with investors, government and customers, and how Shell used philanthropy to tackle the problem of “low credibility and trust” amid “rising societal expectations on climate action” while ensuring that oil and gas remained “a profitable cash engine.”

As the Trump administration rolls back environmental protections and slashes U.S. climate commitments, the documents cast new light on the oil industry’s long-term strategy to burnish its reputation and influence policy through partnerships with groups as diverse as the Girl Scouts of the USA, Ford’s Theatre, the U.S. Olympic Committee, the Chicago Architecture Biennial and the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo.

“Big Oil exploits its partnerships with some of America’s most trusted institutions, to greenwash its image, block progress on climate safety, and avoid accountability for the escalating costs of climate-driven disasters,” said Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), who helped lead the congressional investigation as then-chair of the Senate Budget Committee.

The congressional investigators’ final report, published in April 2024, found that while BP, Chevron, and Shell publicly claimed to support pro-climate reforms between 2015 and 2021, they continued to underinvest in cleaner energies and increase oil and gas production.

All three companies also lobbied against climate policies during this time through trade groups such as the API, the Western States Petroleum Association, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. The measures ranged from export restrictions on liquefied natural gas (LNG), certain state carbon taxes, and fracking moratoriums to policies relating to electric vehicles as well as regulations designed to reduce emissions of the powerful greenhouse gas methane. These efforts were documented in their own in-house publications, as well as reports by climate accountability groups including Lobby Map and the California Climate Accountability Project.

Most of these climate protections have now been revoked or placed under review by the Trump administration, whose first-day executive order to “unleash American energy” was immediately “applaud[ed]” by current API CEO Mike Sommers.

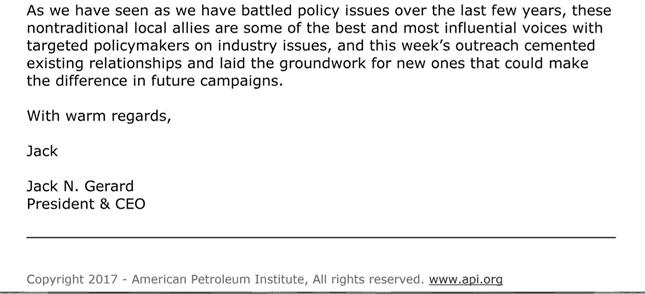

In his 2017 “Executive Update” email to BP praising the value of partnering with the Girl Scouts, API’s then-CEO Gerard also referenced an API-sponsored “Tribute to Black Women luncheon” in Colorado, attended by “1,500 female leaders including more than 27 elected officials and candidates for state office.” The event “allowed API to reach many of the most influential and strong voices for public policy across Colorado.” Gerard also described a STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) tour in Michigan by Grand Hank, a “scientist entertainer who engaged more than 700 students in an interactive way through music, dancing, and experiments.”

API’s efforts had “cemented existing relationships and laid the groundwork for new ones that could make the difference in future campaigns,” concluded Gerard.

“What these sponsorship programs really amount to is an attempt to enhance reputation while continuing to produce fossil fuels, which are leading to the collapse of the climate system,” said Robert J. Brulle, an environmental sociologist at Brown University’s Institute for Environment and Society.

“It’s sort of like giving out life jackets to hurricane survivors,” Brulle said, “while at the same time contributing greenhouse gases to cause the hurricanes.”

BP, Chevron, Shell, and API are among the companies and groups being sued by several U.S. states and municipalities for allegedly defrauding consumers with climate denial and disinformation campaigns.

Speaking on behalf of the industry in 2024, an API spokesperson described such litigation as “meritless” and “politicized,” arguing that “climate policy is for Congress to debate and decide — not the court system.”

BP, Shell, Chevron and API did not respond to requests for comment on their sponsorship programs or the contents of the documents.

ExxonMobil has been another major sponsor of cultural and community organizations. While the subpoenaed documents contain little information relating to its sponsorship programs, Congressional investigators noted that “Exxon withheld multiple documents “for privilege” without specifying the privilege it was claiming and notwithstanding that Congress is not required to recognize common law privilege claims.”

ExxonMobil did not respond to a request for comment.

This article was co-published by The Guardian.

BP’s Strategy to Address ‘Negative Sentiment’

Between 2010 and 2015, BP America’s PR strategy largely focused on rebuilding its reputation following 2010’s deadly and environmentally devastating Deepwater Horizon oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico.

By 2016, however, the documents show that Deepwater Horizon was receding as BP’s biggest reputational concern, with the company pivoting its PR strategy to address threats related to climate action. An internal 2016 summary of “BP America Group-Level Risks,” reported that “although DWH [Deepwater Horizon] is increasingly less of a drag on reputation, other litigation issues present risk to our public standing. Overall negative sentiment about the oil and gas industry also threatens to drag down BP’s reputation.”

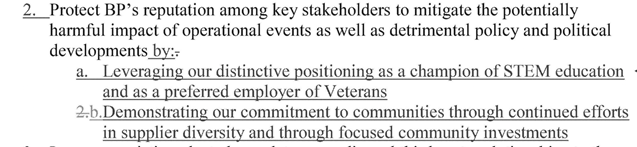

The summary identified the “policy and politics of climate change” as one of the risks capable of causing “damage to BP’s reputation,” with the potential to undermine not only BP’s “public standing and credibility but also investor confidence in the company.”

In response to these threats, a separate “2016 Plan” instructed BP America’s Communications & External Affairs team to “position BP as a leading and trusted voice in the national dialogue” while at the same time to “expand the company’s capacity to influence regulators on key climate-related initiatives.”

The team was told to mitigate the potentially harmful impact of “detrimental policy and political developments” by “leveraging our distinctive position as a champion of STEM education” as well as demonstrating the company’s “commitment to communities,” through sponsorships, which were described as “focused community investments.”

A separate “Strategic Objectives Overview” for 2016 further instructed BP’s communications team to “leverage” sponsorships to “develop support for BP’s business objectives and stimulate advocacy on the company’s behalf.”

These “business objectives” included expanding an Alaskan liquefied natural gas (LNG) operation and developing “major Gulf projects” such as BP’s giant “Mad Dog 2” oil field located several hundred miles east of the Deepwater Horizon disaster site in the Gulf of Mexico.

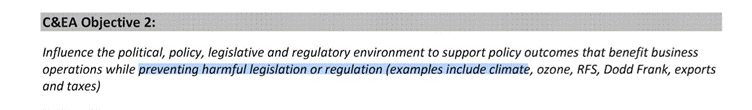

To “protect current operations” and “support business growth,” the team was told to promote policies that favored BP’s business while preventing those that might cause harm — specifically those related to climate. The team should “influence the political, policy, legislative and regulatory environment to support policy outcomes that benefit business operations while preventing harmful legislation or regulation (examples include climate, ozone, RFS [renewable fuel standard], Dodd Frank, exports and taxes),” declared the memo.

In 2016, BP America’s sponsorships included the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the “BP MS 150” bike ride from Houston to Austin, the National Urban League, the Women’s Energy Network, and the Valor Games competition for veterans. The BP Foundation also sponsored multiple STEM programs across the country.

‘Strategic Relationships’

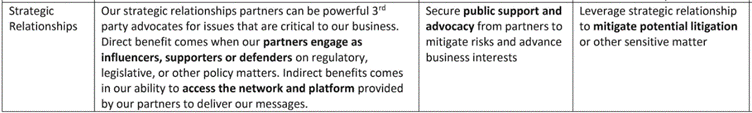

That same year, a BP External Affairs memo demonstrated different ways that sponsorships, referred to as “strategic relationships,” presented opportunities to “advance business interests” by securing “public support” from partners, as well as to “mitigate risks including those posed by “potential litigation.”

By April 2016, three attorneys general – from Massachusetts, New York, and the U.S. Virgin Islands – were investigating whether to sue BP rival ExxonMobil for deceiving the public about climate change risks, or misleading investors over how those risks could hurt business. Members of Congress and candidates for state office were also questioning the role of other fossil fuel companies in spreading disinformation on the climate crisis.

Outlining the precise “Business Benefit” afforded by sponsorships, the BP External Affairs memo stated: “Direct benefit comes when our partners engage as influencers, supporters or defenders regulatory, legislative, or other policy matters, while indirect benefits comes [sic] in our ability to access the network and platform provided by our partners to deliver our messages.”

A further goal was to “leverage” BP’s “strategic relationships to mitigate potential litigation or other sensitive matter [sic],” the memo said.

‘Defend BP Budget’

In June 2017, hundreds of thousands of people took part in the People’s Climate March in Washington, D.C. to protest the first Trump administration’s withdrawal of the U.S. from the Paris Agreement

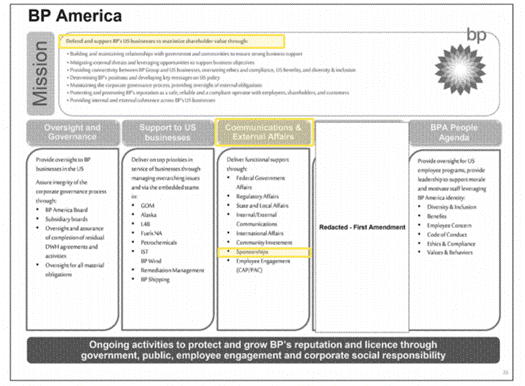

Six weeks later, a BP America “Key Priorities Review” directed communications staff to use sponsorships as a way of “mitigating external threats” as well as “building and maintaining relationships with government and communities to ensure strong business support.”

According to the review, sponsorships should deliver “functional support” for the company’s central “mission” of defending and supporting its U.S. business.

The review described “community investment” and sponsorships as key “ongoing activities to protect and grow BP’s reputation and license” — a reference to maintaining sufficient legitimacy, credibility and trust to sustain the public’s acceptance of its business practices.

A “Defend BP Budget” document that accompanied this review listed some of the company’s U.S. sponsorship payouts, including $1.2 million to the U.S. Olympic Committee for the paralympics team, $500,000 to the Chicago Architecture Biennial, and $300,000 to the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo.

In 2019, a “Strategic Plan” for the launch of BP’s partnership with the American Heart Association (AHA) revealed that the launch event was designed both to “utilize the AHA’s brand to reach thought leaders, policy makers” and “to raise BP’s brand and contribute to a healthy workplace.”

In response to a request for comment, the AHA stated that “more than 85% of revenue the American Heart Association receives is from individuals, their estates, sale of our educational products and other non-corporate sources. Any funding from the energy industry is an infinitesimal part of that 15% of total corporate revenue from all sectors.”

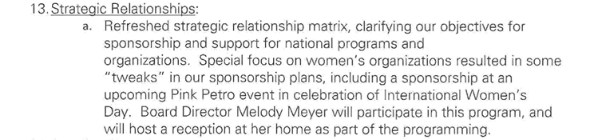

A separate 2019 “Executive Team Meeting” memo suggested that BP tailor its sponsorship programs according to prevailing cultural trends, in this case by aligning with the #MeToo movement.

The company’s “strategic relationship matrix” had been “refreshed,” stated the memo, with a “special focus on women’s organizations.” Handwritten notes on the subpoenaed copy of the document described the #MeToo movement as an example of a rapidly mobilizing “new agenda.”

BP’s “tweaks” to its sponsorship plans included an upcoming International Women’s Day event called “Pink Petro.” Melody Meyer, a female BP board member, was to “participate in this program [and] host a reception at her home as part of the programming.”

A confidential internal memo, dated July 29, 2020, argued that BP’s $200,000 annual sponsorship of Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. was justified on the grounds that it boosted the company’s public image via “on-stage recognition and program recognition,” and provided “elevated access to and recognition with critical Washington stakeholders.” “Members of Congress, the Administration [sic] and more” regularly attend Ford’s Theatre VIP Opening performances, receptions, and events,” noted the memo, which also extolled the benefits of BP America’s then-president and board chair Susan Dio’s seat on the theatre’s board of trustees: “The value of the Trustee role is access to DC political figures.”

Backing the British Museum

Beyond BP’s operations in the U.S., an April 2016 internal “BP position” document, instructed “authorized recipients” to emphasize the message that over 50 million people in the UK had “engaged with a BP-supported activity” thanks to its arts and culture sponsorship of the British Museum, Royal Shakespeare Company, Tate Britain, and other institutions.

Another message for staff to convey while discussing these UK sponsorships was that BP was “a fossil fuel company that is playing its part in addressing the climate challenge by advocating for a carbon price, providing lower carbon products like gas and renewables, pursuing energy efficiency and supporting research.”

According to a “2020 review” produced by the company’s Policy and Advocacy Working Group, official positions like these formed the basis for ‘high-level’ external messaging” to be used at BP “investor events,” in “executive speeches and opeds [sic],” as “responses to press inquiries” and during “civil society (NGO) engagement.”

The following year, in 2021, a BP communications and advocacy team memo instructed staff to “pivot existing sponsorships” to “mitigate social risks of the business” and “showcase bp as a British champion.”

“These documents make it abundantly clear that BP’s cultural sponsorship has nothing to do with philanthropy,” said Chris Garrard, director of the campaign group Culture Unstained, which is calling on those UK arts and cultural institutions that have not already cut ties with the fossil fuel industry to do so.

Rather, he said, sponsorships are “a strategic attempt to access high-level decision makers, to secure the public backing of leading cultural figures, and to craft a positive public image.”

In Garrard’s opinion, sponsorship is not a donation. “It is a transaction that furthers BP’s business interests, resulting in more fossil fuel expansion, and empowering their broader political lobbying to impede international climate action,” he said.

Shell Seeks a Buffer Against ‘Negative News’

In 2016, Shell was also pursuing sponsorships as a means to improve its reputation with the U.S. public.

A PowerPoint presentation for a 2016 Shell “Reputation Workshop” noted that “trust in the energy industry” was “low,” and declared climate change “an emerging issue.”

To aid the company’s reputational planning, Shell identified social and community-based groups as well as emergency and other aid organizations, as potential “business-critical US stakeholders,” which should be assessed “for opportunities that advance Shell business and reputational objectives.”

The following year, an “influencer insight” report revealed why the company saw not-for-profit partners as “stakeholders/influencers.” According to this report, “community engagement” and “philanthropy” were helping Shell cultivate public trust, which in turn would “buffer” the company “in the face of negative news.”

Shell’s hoped-for outcomes were to strengthen “stakeholder inclination to speak up for Shell” and “in some circumstances [defend] Shell from critics.”

In 2019, following Trump’s withdrawal of the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, Shell saw an opportunity to take on “an increased leadership role to shape effective policy at multiple levels,” according to a high-level internal discussion document produced for the company’s executive committee. The policies mentioned ranged from carbon pricing, to boosting support for government subsidies for carbon capture and storage technology.

According to the document, this could be done “while maintaining a strong societal license to operate.” The document emphasized the importance of protecting Shell’s traditional business, stating that its oil and gas operations required “continuous efforts to remain a “profitable cash engine,” identifying “an opportunity to leverage America’s abundant shale gas for LNG exports” and pronouncing that “in the near to medium term, oil and gas will continue to play a key role for the US, both at home and globally.”

However, the discussion document also noted that “following the 2018 midterm elections, climate change has once again become a topic in Washington, D.C.” and that the Green New Deal legislation proposed by Democrats “has helped propel climate change onto the agendas of both the Democrats and Republicans.” Shell predicted that climate change will be a key issue in the upcoming presidential campaigns.”

An accompanying “Reputation Plan” also highlighted the problem of “low credibility and trust” amid “rising societal expectations on climate action,” especially for “onshore unconventional exploration and production,” a reference to fracking.

Shell outlined key ways to overcome this problem, such as “secure partnerships with credible external influencers” that “support and strengthen societal license to operate and grow at country and asset level,” and “make meaningful, authentic connections with people.”

By engaging with “Non-profit (NGO) Influencers / Special Publics,” Shell believed it could develop a “network of third-party advocates” and portray itself as a “preferred partner in energy transitions.”

The reputation plan included a list of influencers to engage with — which Shell blacked out before giving the document to Congress.

Records show that in 2019 Shell sponsored the Houston Open (a golf event the company had sponsored for 26 years); the Houston Mayor’s Back 2 School Festival; the Shell Game-Changer Open House at the SXSW Festival in Austin; the Shell Eco-Marathon Americas in California (a U.S. chapter of the company’s global student competition program); the 100 Resilient Cities Network (which Shell began sponsoring following Hurricane Harvey); the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival (which the company began sponsoring in 2006 following Hurricane Katrina); and the United Negro College Fund Walk for Education.

In response to a request for comment the SXSW Festival said: “Neither Shell nor any other fossil fuel companies are participating at SXSW 2025 as clients or sponsors.”

None of the other organizations or individuals receiving sponsorship from oil companies referenced in this story responded to requests for comment.

Shell did not respond to inquiries about the redacted material.

Chevron Uses Sponsorships to ‘Advance Business Objectives’

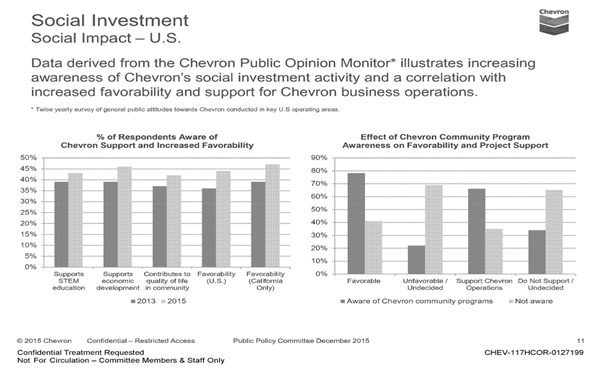

Chevron saw its sponsorship programs — which it termed “social investments” — as “a key engagement tool to build and reinforce brand awareness and favorability.”

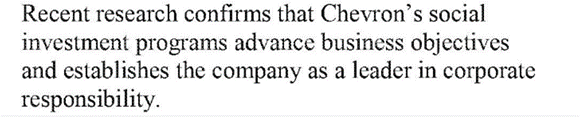

A 2015 confidential briefing document, produced for the Chevron board’s public policy committee, stated that the company’s “social investment programs advance business objectives and establishes [sic] the company as a leader in corporate responsibility.”

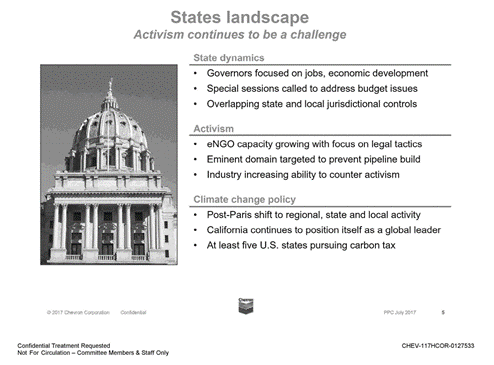

The internal brief identified “U.S. Federal Climate Policy” as one of the risks that could affect the company’s business, highlighting that the Obama administration continued “to drive an aggressive regulatory agenda designed to cement the President’s climate and environmental legacy.” On the state and local levels, the brief noted that “activism continues against industry.”

The brief highlighted two areas of special concern: Some communities and civil society organizations were “attempting to link human rights to climate change and hydraulic fracturing debates,” and others were calling for fossil fuel companies to pay for the costs of climate impacts.

The brief also summarized the positive value of Chevron’s sponsorship efforts, citing public opinion surveys showing that when people were familiar with these sponsorship programs, their attitudes about the company were more favorable, increasing “support for our operations in their communities by a margin of 2:1.”

By 2017, records show that Chevron was sponsoring organizations such as the Society of Women Engineers and the National Action Council for Minorities in Engineering. The company’s own Appalachia Partnership Initiative was directing funding to projects in communities located near Chevron’s fracking operations in the Marcellus Shale, such as ShaleNET scholarships for regional workforces and the Inquire Within rural library program.

In July 2017, two months after the People’s Climate March, “an updated list of key global policy issues that can impact Chevron’s business” (prepared for a meeting of the same public policy committee) included “off-oil activism” in the U.S. The document characterized this activism as “aimed at transitioning to a low carbon economy” by “convincing the public and policymakers that economic growth can be decoupled from [greenhouse gas] emissions and that society can be powered by renewable energy.”

Chevron noted that this message was “being propagated to strengthen public support for anti-fossil fuel ballot initiatives, pressure consumer facing companies to make renewable energy and climate commitments, provoke protests involving physical disruption of infrastructure development, and significantly increase non-governmental organization (NGO) fundraising.”

In light of these threats, board members were assured that “Chevron’s global [social investment] activity remains focused on areas aligned with our business needs.”

That year, Chevron sponsored the annual Chevron Houston Marathon, attracting over 300,000 people (an event the company began supporting in 2005), along with famous cultural organizations such as the San Francisco Symphony and the Smithsonian Institution.

A separate “Brand Positioning Brief,” also prepared for the July 2017 committee meeting, declared that “[T]oday more than ever, effective brand and reputation management is critical.” The brief described Chevron’s sponsorships as “a key engagement tool to build and reinforce” the company’s “brand awareness and favorability.”

The documents show that at the same time Chevron was seeking to bolster its reputation through sponsorships, the company was also closely monitoring developments in domestic climate policy, as well as tracking the continued momentum of what it termed an “anti-fossil fuel agenda” being pursued by climate activists and “leading environmental NGOs.”

A 2017 Chevron “Public Policy Update” reported that while activism was a continuing challenge at the state level, the fossil fuel industry was increasing its “ability to counter activism.”

On international climate policy, Chevron noted that “many governments in countries key to Chevron are adapting policies…to address climate change and to meet their [Paris] Agreement goals.”

An internal briefing document, prepared for the company’s board of directors ahead of a 2016 tour of Australia, stated that “partnerships are essential to our ability to develop energy resources. We build long-term, mutually beneficial relationships with host governments, national and international energy companies, and nongovernmental organizations.”

The briefing listed the community benefits achieved through Chevron’s support of Australian cultural events and groups such as the Chevron Focus Environment photography competition, the Perth International Arts Festival, and Many Rivers Microfinance. The document also emphasized that the company’s strategic partnerships “focus on maximising return on investment and help the ABU [Australian Business Unit] achieve its long-term business objectives.”

Chevron did not respond to a request for comment.

‘Denial and Doublespeak’

In their final report, titled “Denial, Disinformation, and Doublespeak,” the congressional investigators who subpoenaed the documents found that between 2015 and 2021, all of the companies examined (which also included ExxonMobil) “routinely misled the public and investors” about their emission reduction targets, plans to comply with the Paris Agreement, and commitments to support various climate policies.

“Big Oil’s multi-pronged scheme to lock in fossil fuel dependence relies on masquerading as a trusted clean energy partner,” said Sen. Whitehouse. “Just as Big Tobacco lied about the harms of its products to deceive the public, Big Oil is perpetrating a similar disinformation campaign against the American people, policymakers, and its investors.”

In the U.S. and around the world, oil and gas companies continue to sponsor cultural and community groups.

Following Hurricane Helene in September 2024, Chevron announced a donation of $250,000 to groups assisting with relief and recovery efforts. In January, as wildfires devastated parts of Los Angeles, Chevron announced a $1 million donation “to support relief efforts.”

The costs of these disasters are markedly higher. Hurricane Helene is estimated to have caused $59.6 billion worth of damage, and its destructive power was made 200-500 times more likely by the burning of fossil fuels, according to scientists at the World Weather Attribution project. Damages from the Los Angeles fires are estimated at $250 to $275 billion, according to AccuWeather.

A January study involving over 30 researchers worldwide found that climate change made the chances of such fires 35 percent more likely in 2025 compared to pre-industrial times.

Sponsorships of the Girl Scouts, museum exhibitions, and marathons “in no way make up for the damage that the fossil fuel companies are causing. It also buys the corporations more time to continue their business-as-usual model,” said Brulle, the sociologist at Brown University. “It fits to the larger strategy of the fossil fuel companies to maintain their business practices as usual for as long as possible to maximize their profits.”

Additional reporting by Kate Dario.

This article was co-published by The Guardian.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts