This investigation has been translated into French. You can read it on DeSmog here

At the entrance to the fish market on the outskirts of Joal Fadiouth, a coastal town in central Senegal, a group of women have set up shop under the shade of a small pavilion.

The market used to bustle with ice cream sellers, salt vendors and horse-drawn carts bringing fish from the beach. Today, trade is dead: “Without fish, we have no money to send our children to school, buy food or get help if we fall ill,” says trader Aissatou Wade.

Wade blames Omega Fishing, a nearby factory on the Atlantic shoreline. Senegal’s largest exporter of fishmeal and oil, the plant grinds up small, edible wild fish to fuel a global trade in feed for farmed seafood.

Since Omega Fishing opened in 2011, its buyers have steadily priced women fish traders out of the market, paying twice what they can for a box of fish. In the last four years, the number of local women braising, sun-drying and salting fish – such as silvery sardinellas and bongas – into small, affordable portions, has dropped from 650 to just a few hundred.

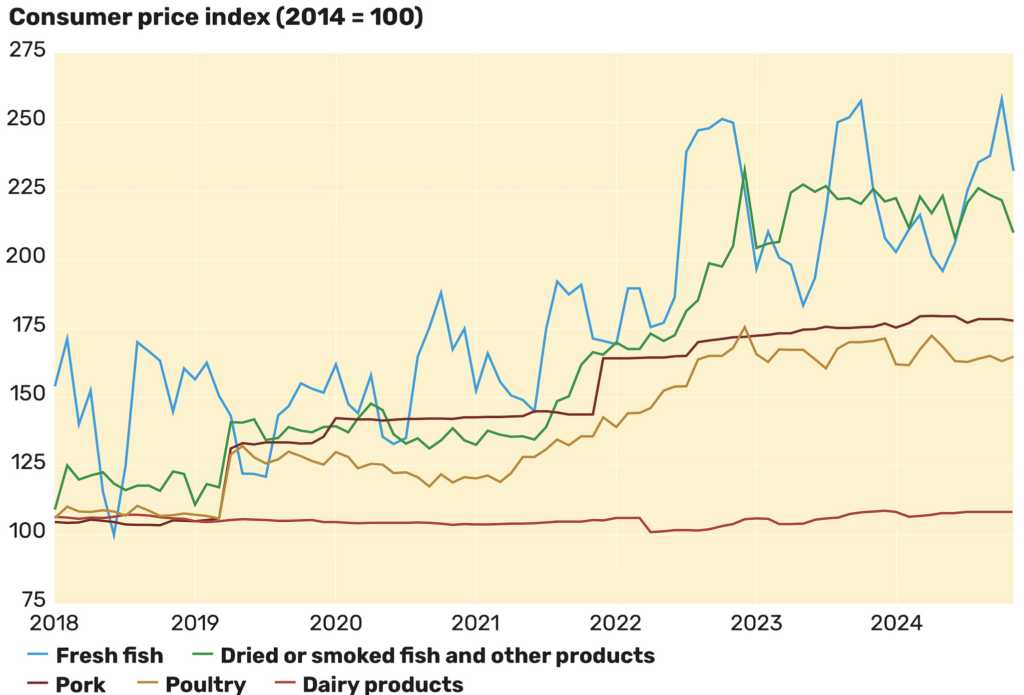

Sardinella is also disappearing from dinner tables. In the last six years, as fishmeal exports have jumped, prices for dried and fresh fish have more than doubled, in a country where over half the population can’t afford a healthy diet.

The number of fish in the sea has plummeted, too. Since the fishmeal industry took off in West Africa about 15 years ago, round sardinella stocks have fallen to their lowest level ever recorded – with demand from the factories exacerbating the pressures of over-exploitation by foreign boats and climate change, which is causing waters to warm, sending fish northwards.

In Senegal, sardinella catches have crashed from annual landings that fluctuated between 100,000 and 250,000 tonnes between 2010-2020, to just 10,000 tonnes for the last four years. A report out earlier this month from the Environmental Justice Foundation cited research that shows 57 per cent of fish populations in Senegal are in a similar state of collapse.

“It’s a catastrophe,” Abdou Karim Sall, the head of an artisanal fishers platform Papas in Joal, says flatly.

This investigation was co-published with The Guardian.

Until now, an opaque seafood supply chain has obscured which companies are profiting. But a two-year cross-border investigation by DeSmog and The Guardian shows that UK shoppers may inadvertently be taking fish from West African plates, via a combination of poorly regulated fishing and labelling loopholes.

Reporters reviewed hundreds of pages of customs data, in-store package, and supplier lists, and spoke to industry sources by phone and at the Seafood Expo North America in Boston – one of the industry’s biggest trade fairs.

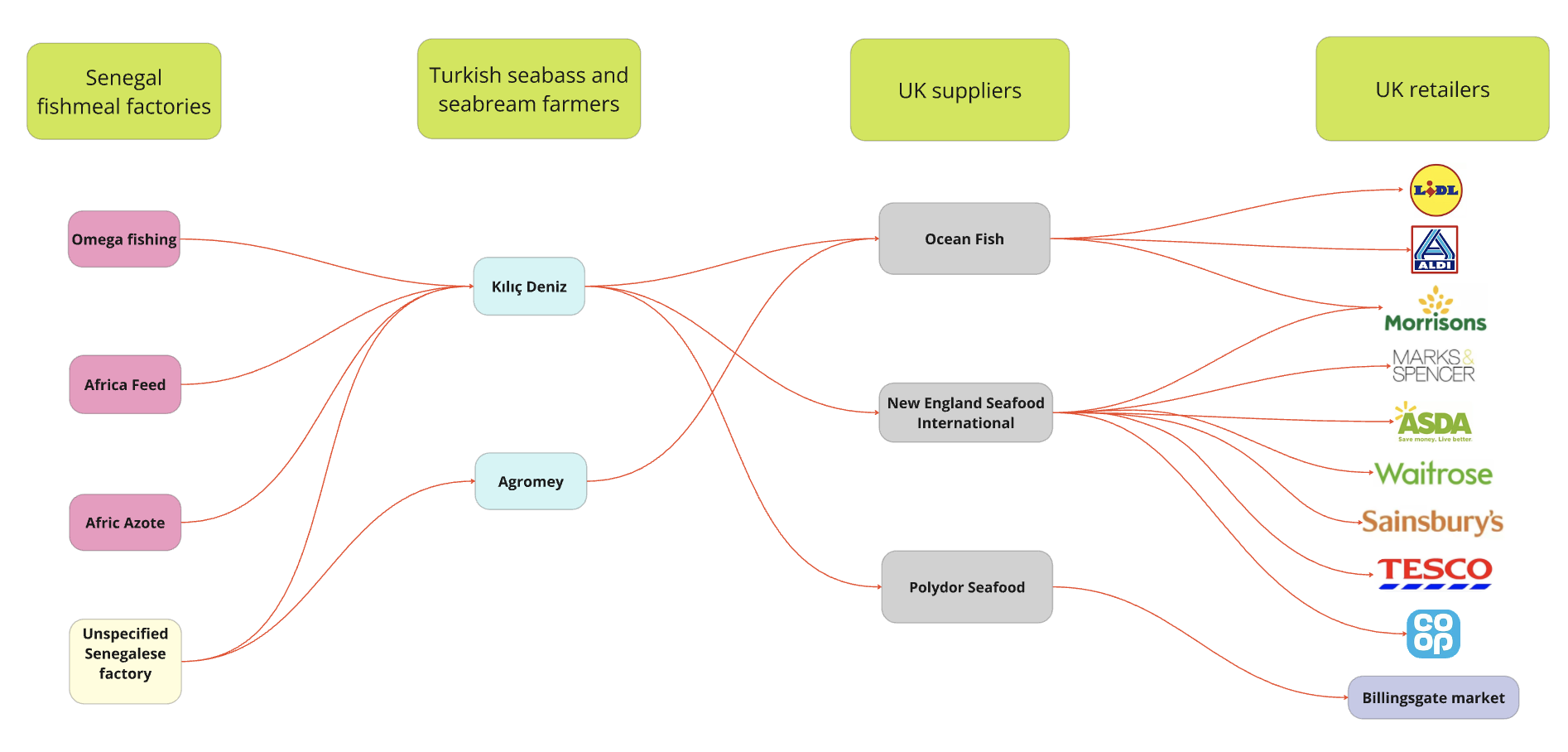

The investigation reveals that at least five UK supermarkets – Waitrose, Co-op, Aldi, Lidl and Asda – have sold seabass or seabream grown by one of Turkey’s largest fish farmers, Kılıç Deniz, which sources fishmeal made from small Senegalese fish.

These retailers are supplied by two UK wholesalers – New England Seafood International and Ocean Fish. The investigation has found that these two wholesalers have also sold seabass and seabream to Marks & Spencer, Morrisons, Sainsbury’s and Tesco – although these supermarkets declined to tell DeSmog whether that fish came from Kılıç or another seabass supplier.

Between them, these wholesalers have supplied supermarkets with 473 tonnes of fish raised by Kılıç, or its subsidiary Agromey, over the past four years, according to official data. That’s enough fish to stack supermarket shelves with nearly 5 million fillets. [1]

All this fish appeared on supermarket shelves labelled “responsibly sourced” or “responsibly farmed”, based on certification from the Aquaculture Stewardship Council and other standards bodies.

“Farmed fish comes as this nice product, all the same size, good for the consumer, and no one knows it is jeopardizing the prospects of people in West Africa,” says Beatrice Gorez from the Coalition for Fair Fisheries Arrangements, CFFA.

Naturalist and broadcaster Chris Packham says the investigation shows British supermarkets are in “dereliction of their duty” over food sourcing. “How do you make an ethical choice in a supermarket aisle, if food labelling is so appalling that you’re incapable of doing so?” he says.

DeSmog’s findings reveal modern day “ecological colonialism” in a broken food system, according to Aliou Ba, Senior Oceans Campaigner at Greenpeace Africa. “Fish caught on African coasts must feed Africans first” he says. “Retailers must stop being complicit in this exploitative system, which prioritises profits over the fundamental right to food security.”

A booming trade

The fishmeal factories on the West African coastline are voracious consumers of the small fish nourished by a natural upwelling system in the North Atlantic.

These “pelagic” or “forage” fish – which include species of mackerel, bonga and bumpers – are the mainstay of small-scale fisheries in Africa, which furnish over a quarter of the micronutrients – such as zinc, iron and omega 3 – needed by 181 million people.

The farmed fish industry – the world’s fastest-growing food sector – has a huge appetite for pelagic species, which are ground into fishmeal and oil and used to feed fish grown in cages. Nearly a quarter of the global catch of all wild-caught species – 17 million tonnes – was swallowed up by the marine ingredients industry in 2022, with around 85 percent of this fed to farmed fish.

The majority of feed fish come from Peru, but West Africa’s fishmeal exports have grown exponentially in the last decade, consuming an estimated half a million tonnes of fish a year. Some of these are processed by Senegal’s six registered factories – owned by various national and Chinese investors.

While the first few plants built in the 1970s were supposed to use only waste products (fish heads, tails, rotten tissue), as the price of fishmeal has risen, Alassane Samba, the retired head of the oceanographic research centre in Dakar (CRODT) tells DeSmog the new generation of factories use fresh whole fish, a claim backed by a 2022 report by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and an aquaculture industry-sponsored report from 2024. It’s the same story in neighbouring Gambia, which has another three fishmeal plants and Mauritania, the epicentre of the trade, which is home to 35 more.

The farmed seafood industry says it plays a “vital role in global food security”, and downplays its reliance on edible fish. Salmon companies have run into repeated scandals for sourcing from chronically undernourished sub-Saharan Africa, prompting some fishfeed companies to state in sourcing policies that they avoid Senegal.

Fish-Farming Powerhouse

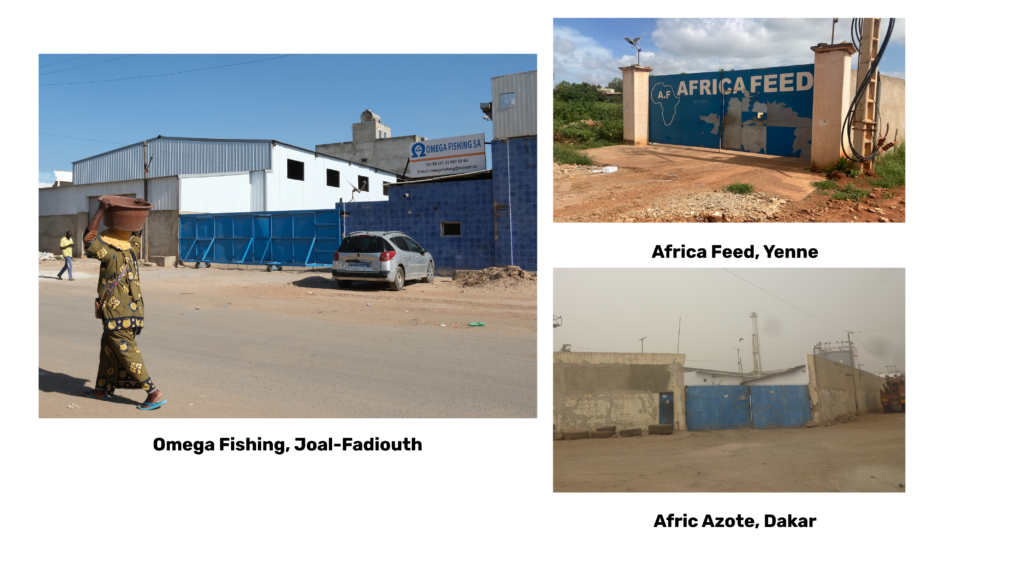

The DeSmog-Guardian investigation – based on trade data, shipping records and reporting in three countries – can confirm that Turkish-farmed seabass and seabream is being fed on fishmeal exported from three factories in Senegal: Omega Fishing and Africa Feed south of the capital Dakar, and Afric Azote at Dakar port.

Surrounded by sea on all sides, Turkey is a fish-farming powerhouse, supplying more than half of the world’s seabass and a third of its seabream. The country’s aquaculture industry has nearly doubled in size in the last decade, according to official figures, and farmed over 1 million tonnes of fish in 2023. Having decimated its anchovy stock in the Black Sea, Turkish fish farmers now import most of their fishmeal.

Founded as a family business 34 years ago, and now employing over 2,500 people, Kılıç is one of Turkey’s leading seabass and bream producers – and the biggest importer of Senegalese fishmeal among 12 Turkish rivals. The company has shipped fishmeal and fish oil from Senegal every year for the last four years, adding up to at least 5,400 tonnes, customs data shows.

The volume of fresh fish used to make that fishmeal in those four years would have been enough to meet the recommended dietary intake for nearly two million people, according to DeSmog calculations based on Eat Lancet dietary recommendations. [2]

In an email, Kılıç told DeSmog it was not breaking any laws by buying raw materials from Senegal, and that it “did not manage other countries’ fishing policies”. Acknowledging “concerns in world public opinion” Kılıç added: “we think we can limit our purchases from Senegal”.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts

Senegalese fishmeal and oil made up less than 1 percent of its total purchases in 2024, the company said, adding that the fish used were bigeye grunts and bumpers, which it claimed were “not caught for human consumption.”

But fishmonger Aby Diouf, and other sources in Senegal, told DeSmog that factories are “using the fish that we eat” – including the species listed by Kılıç, which are consumed fermented or fresh, in slow-cooked stews with couscous and rice.

And for a company farming 65 million tonnes of fish a year – and generating $445 million in annual revenues – even 1 percent of its purchases of fishmeal has an outsized impact in Senegal.

“Changes that seem small at a global scale can have devastating consequences locally,” explains environmental scientist Christina Hicks, an expert on small-scale fisheries and nutrition at Lancaster University.

In 2023, a year that saw fishmeal exports climb to an eight-year high, persistently high food costs pushed Senegal into crisis-levels of hunger for the first time on record.

Poor-quality diets can stunt children’s growth, impair cognition and cause a life-long susceptibility to disease, as a study co-authored by Hicks noted earlier this year.

Price of dried and fresh fish rising steeply in Senegal over the past few years

Malnutrition, Job Losses and Pollution

In the 10 years to 2020, the Senegalese have gone from eating 16 kilos of pelagic fish a year to less than seven, according to FAO data.

Meanwhile, across West Africa, the number of people unable to afford a healthy diet has climbed to nearly 70 percent – compared to 2.3 percent in Western Europe, where the majority of farmed seabass is consumed.

“This investigation reveals a very specific instance of what we have noticed from larger datasets,” says Jennifer Jacquet, a professor of environmental science and policy at the University of Miami. “Food secure consumers are benefitting from the fishmeal and oil from small fish caught from regions where there are high amounts of food insecurity.”

The fishmonger Aby Diouf says 500 grammes of keccax (dried and smoked sardinella), which used to cost £0.13 (CFA Francs 100), now costs as much as £1- £2, depending on the season.

Speaking on the beach at Popenguine, north of Joal-Fadiouth, Diouf remembers trading keccax as far inland as Mali and Burkina Faso.

Back then, fish workers were the fulcrum of a thriving, informal trade, which in 2022 was estimated to employ an estimated 40,000 women in Senegal. Now much of that fish is sold to the factories, bypassing the women who wait on the shore to buy it.

“We were proud,” she says. “We built our houses, we bought cars. We bought boats for our husbands – we even financed their fishing trips.”

Diouf, who raised and educated her seven of children from the trade, now rents out plastic chairs for baptisms and weddings – and has sold two of her three freezers.

Women fish processors in Diouf’s village are even worse off – “tired, sick” and falling into debt, while in Yenne, home to fishmeal factory Africa Feed, nearby fish-smoking ovens rust in the sun. Thousands of women have lost their jobs in recent years, estimates Didier Gascuel, a fisheries ecologist at the Institut Agro Rennes-Angers in western France, who has lived and worked in Senegal.

Factories are making people physically sick too, local people say. Residents complain of foul, suffocating smells and polluted waterways in towns that host fishmeal plants, including Omega Fishing and Africa feed, which both sell to fish farms that supply the UK, according to customs data.

In Joal-Fadiouth, pollution from Omega Fishing has sparked protests. “People are experiencing respiratory illnesses, dizziness, headaches, and vomiting,” Mamadou Faye, one of the movement’s co-founders, told Danwatch earlier this year.

Located next to homes, in violation of Senegal’s environmental code, the clouds of black smoke from Omega’s chimneys are causing asthma, according to local doctor Papis Gueye.

Omega Fishing and Africa Feed did not respond to requests for comment.

Collapsing Fish Stocks

Seeking to lure foreign investment to help tackle a $5.75 billion trade deficit and $40 billion in foreign debt, the government offers financial sweeteners to the fishmeal industry, including a 50 percent discount on income tax and exemption from import duties.

In the short term, Senegal’s artisanal fishing fleet of 18,000 colourful canoes or pirogues, equipped with motors, GPS and galoshes for the crew, appeared to benefit from a guaranteed market for its catch.

But the gold-rush mentality has come back to bite fishers too.

“Before the fishmeal industry came here, there were plenty of fish in our inland waters,” says Cheikh Mbengue, the head of the local fishing association at Yenne, where the factory Africa Feed opened in 2014. “Now, you have to go far out to sea if you want to catch anything”.

“The sector is absolutely in a state of crisis,” says Gascuel, the fisheries ecologist. “And it is largely – though not only – linked to this development of fishmeal industries, which have been set up over the last ten years.”

Gascuel says that women are defrosting and re-selling frozen imported sardines – “mind-blowing stories” in what was – until recently – one of the world’s most abundant fisheries. At the fish market in Dakar, fish seller Mama Fanta says she is selling croaker, an imported farmed fish from Oman, because “there’s nothing else left”.

“We are entering danger zones that are very difficult to predict,” says Gascuel. “It is clear that overexploitation combined with the effects of climate change and water degradation can lead to collapse phenomena.”

The Senegalese-owned factory Afric Azote denies that it contributes to overfishing or women’s unemployment.

“It’s a misguided view to claim that fishmeal factories use the fish that should go to the local population,” a staff member told our investigations team from behind a desk at the plant, which overlooks huge piles of shipping containers piled up in the port of Dakar. “I’d even call it 100 percent wrong. Almost everything we produce here is made of waste products”.

The employee, however, opened up an Excel-sheet on the screen that showed that in December 2024 nearly 40 percent of fishmeal was made with whole fish.

“I will not dispute we also use fresh fish here in the factory,” the staff member added, in light of the figures. “If you’ve seen sardinella here, that’s possible. But if you follow the money, you will see it’s not profitable for us to buy much at market prices.”

Afric Azote said that whole fish is only used when it is unsold because the catch is too large for women processors to absorb, or the fish is rotten.

Nevertheless, a dozen sources – women traders, wholesalers and fishermen – said that factories routinely buy fresh fish.

“Senegal has never been able – has never tried – to regulate this problem of buying fish on the beach,” says Alassane Samba, the retired oceanographic research centre head.

It is also common for fishmeal factories to buy juvenile fish, an illegal practice in Senegal that is further imperiling the stock, according to public officials and fishermen and women traders’ organizations.

Afric Azote said: “All fishing docks are supervised by fisheries officers, who check the size of fish landed. We systematically refuse any fish that is not the legal size.”

Omega Fishing denied using juvenile fish during a factory visit by our investigations team in 2023.

The Senegalese government did not respond to requests for comment.

Onto Your Plate

Senegal’s fishmeal is exported from Dakar port to southwestern Turkey, the heart of the country’s burgeoning aquaculture industry – and site of Kılıç’s feed mill.

Here, fishmeal is mixed with wheat, soy, fish oil and other ingredients to feed the millions of fish Kılıç harvests from the Aegean Sea every year.

Some of that fish travels frozen, overland or by boat in 18-tonne containers to Liverpool, Portsmouth, Dover and Hull.

Of the more than 5,760 tonnes of seabass and 647 tonnes of seabream British shoppers bought last year, more than 80 per cent was imported from Turkey, according to UK government agency Seafish.

Kılıç features prominently in that trade, making up a quarter of all seabass and seabream imports between 2021 and 2024, according to data from the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) released in response to a freedom of information request.

Seafood grown by Kılıç, or its subsidiary Agromey, has two routes to UK plates. The first is via hubs like London’s Billingsgate market, where men in white overalls and fleeces gather at dawn among boxes brimming full of silvery seabream and seabass – The Guardian found some of them marked “Kılıç”.

“We sell a lot, about 100 tonnes a week,” one trader for UK wholesaler Polydor told The Guardian. “It goes everywhere: fishmongers, Chinese restaurants, the public.”

Defra data shows that Polydor has imported over 7,000 tonnes of seabream from Kılıç in the past four years, equivalent to over 17 million whole fish, or 78 million fillets.[1]

The second route to UK tables is via wholesalers to supermarkets. In 2024, more than half a million fillets of seabass farmed by Kılıç or its subsidiary arrived on supermarket shelves via New England Seafood International, which has offices in Grimsby and Chessington, and Cornwall-based Ocean Fish, Defra data shows.

In an opaque and fragmented supply chain, there’s no way for shoppers to tell if the seabass or seabream filet they’re putting in their basket was fed on fishmeal from Senegal.

But the DeSmog-Guardian investigation has established that Kılıç-produced fish is on sale at Waitrose, which lists the Turkish company as one of its suppliers, while DeSmog also understands that the Co-op sells about six tonnes of seabass farmed by Kılıç a year.

Identification on packaging, supplier lists and conversations with employees of Kılıç, and its subsidiary Agromey, revealed that Lidl, Asda and Aldi have also sourced from Kılıç farms. Sainsbury’s, Tesco, M&S and Morrisons have sourced seabass from New England Seafood International, according to labelling on fillets on sale in supermarket branches and their latest supplier lists, and correspondence with retailers.

When presented with the findings of the investigation, Lidl, Sainsbury’s, Tesco and Waitrose declined to comment, referring The Guardian to a statement from Sophie De Salis, sustainability policy adviser at the British Retail Council: “UK retailers are dedicated to sourcing seafood products responsibly and adhere to all legal requirements around product labelling. They ensure high standards are upheld throughout their supply chains through third party certified verification, which means customers can be assured they are buying sustainably sourced fish.”

Morrisons, Aldi and M&S all said they do not currently source from Kılıç or Agromey farms. Asda did not respond to requests for comment. On its website Asda said it is: “committed to providing safe, affordable and sustainable seafood” to its customers.

A Co-op spokesperson said: “We are committed to sourcing at the highest standards and work closely with our supplier to ensure seabass is sourced from approved farms.”

Of the wholesalers involved in the chain, New England Seafood International said it was dedicated to “sourcing responsible and sustainable seafood”. The other two, Polydor and Ocean Fish, did not respond to requests for comment. On its website, Ocean Fish said it is committed to “responsible fishing practices” throughout its operations.

The links uncovered in this investigation provide only a partial picture of the amount of seabass and bream fed on Senegalese fishmeal arriving in the UK. Three other Turkish fish farmers which supply UK markets also buy west African fishmeal, the investigation found – but it was not possible to trace their products’ journey to their final point of sale.

“Once again industrial fish farming finds itself at the centre of a food security scandal and here is clear evidence that UK retailers are part of the problem,” said Amelia Cookson, campaigner at advocacy group Foodrise. “This investigation shows that companies in the UK are complicit in a long chain of extraction which is inflicting harm on communities in one of the most food-insecure regions of the world.”

‘Responsibly-Sourced’

Despite the destruction caused by fishmeal factories in Senegal, seafood that is fed on small west African fish can still be labelled as sustainable.

Supermarkets label all Turkish seabass and bream on sale from New England Seafood International and Ocean Fish as “responsibly sourced” or “responsibly farmed”. These claims rest on various certifications, which are needed to sell into many European markets. Obtained by Kılıç and other fish farmers, these standards promise “full traceability” of ingredients and responsible sourcing of feed.

Kılıç says on its website that it’s committed to protecting ocean ecosystems and runs an ethics hotline. The company produced a quarter of its seabass and seabream in 2022 from four farms certified to the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) farm standard – considered among the most stringent.

ASC rules state that a farm can only buy fishmeal from sources where fisheries are, at minimum, “reasonably well managed”, with healthy stock – a far cry from the situation in the critically overexploited fishing grounds in Senegal, which received a yellow card from the European Union in May for failing to tackle illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing.

Nevertheless, Kılıç denied it was in breach of ASC standards, saying the organisation’s rules had been overtaken by a new feed standard that takes effect in October, which the company is planning to follow. “It would be very simplistic to conclude that we are not compliant with this standard or that we are misleading customers,” it said.

The ASC said that Senegal was not listed as a sourcing country for whole fish marine ingredients on Kılıç’s 2024 farm audits. It added that in any case, feed fish from Senegal can be mixed into feed, as long as the balance of ingredients meets its standards.

“The ASC has many loopholes,” explains a consultant who has worked in certification for the last 15 years, who asked not to be named for fear of professional repercussions. “You have a standard, but it doesn’t mean that you have to meet the standard fully to get certified”.

Campaigner and founder of the Green Britain Foundation, Dale Vince, says the British public are being sold a “fairy story” of responsible sourcing and that accreditation or assurance schemes are “clearly not enough”.

Turkey’s Polluted Seas

More than 3,000 miles away from the coast of Senegal, fish farm ownership in Turkey is “guarded like a state secret” according to aquaculture engineer-turned-activist Levent Erkol – making it hard for communities to know whether companies are abiding by domestic laws designed to protect ecosystems from the release of feed, antibiotics and waste into the sea.

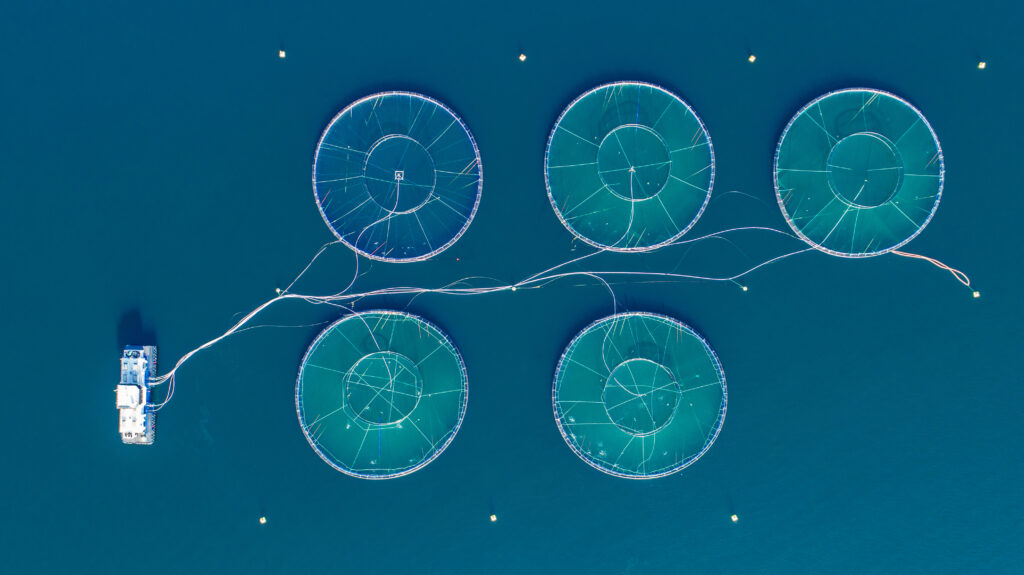

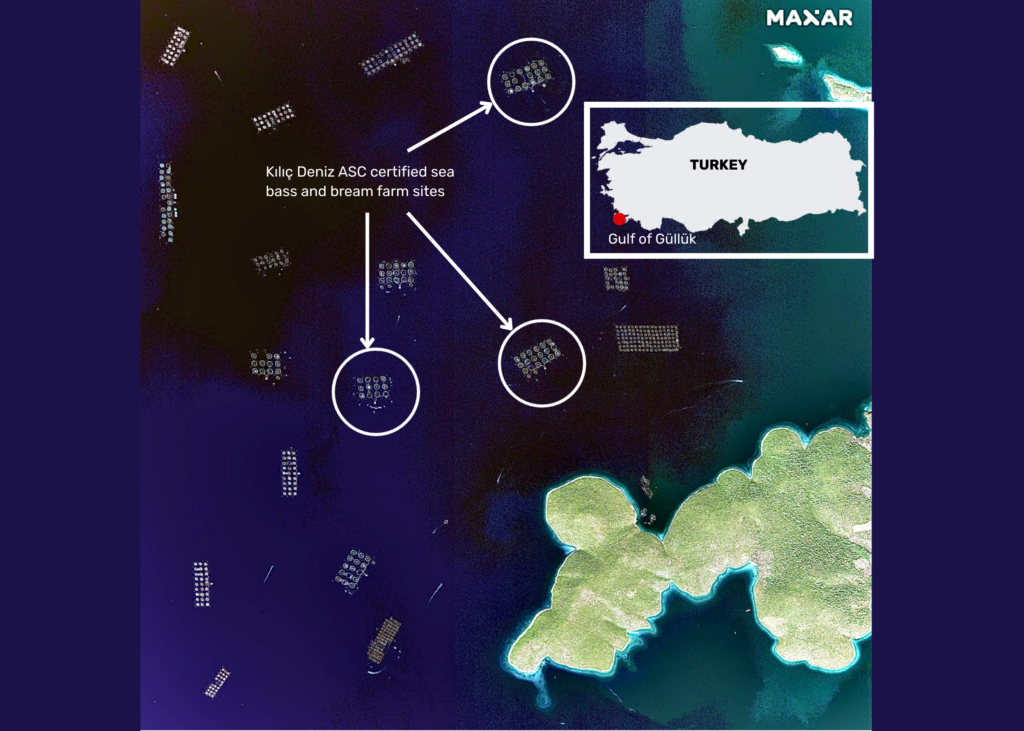

Using satellite data and co-ordinates on the ASC website, DeSmog was able to locate three of Kılıç’s seabass and bream cages in the Gulf of Güllük, a short drive from its feed factory.

Erkol sees growing evidence of pollution from at least 20 off-shore fish farms in the gulf. The still waters are turbid and murky; fish food leaves the surface of the sea covered with a greasy film, and has also attracted invasive species, such as the venomous lionfish.

“Farms are increasing in number and size every day,” Erkol said, pointing towards the horizon where cages form a dark scribble on the surface of the water.

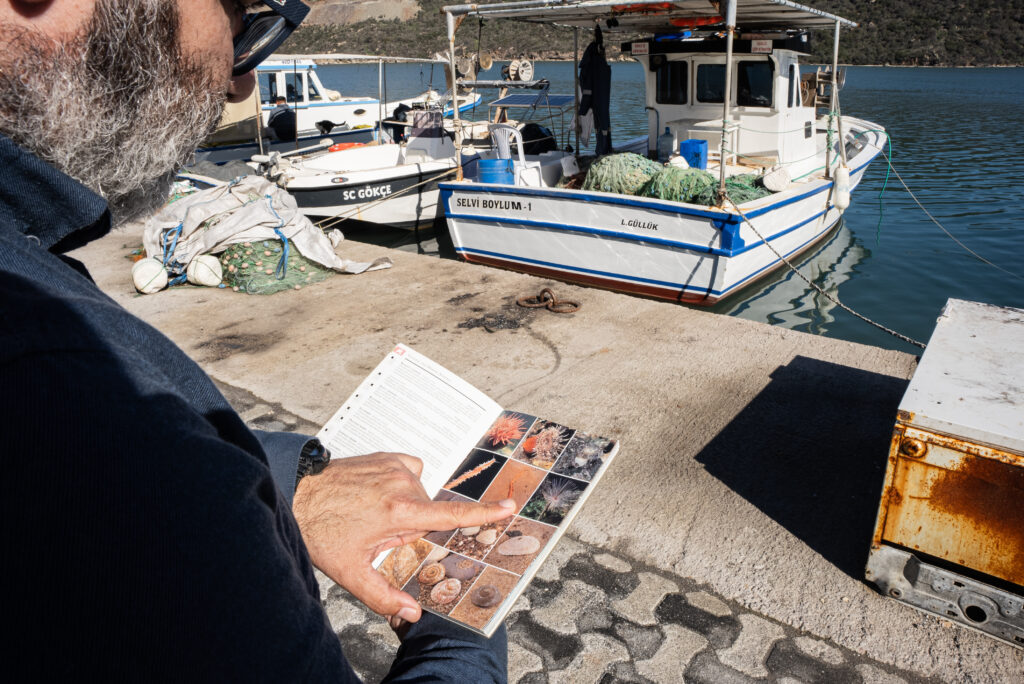

Leafing through a nature book, Erkol points out the indigenous species of anemones, starfish and rare sea urchins that are in decline due to a build-up of feed waste and fish faeces on the sea bed. He says protected seagrass – which acts as a nursery for wild fish, and sequesters carbon – is also shrinking. Scientists’ warnings of damage to important lagoon ecosystems and subsequent protests have been ignored.

“We earn millions of dollars from this sector, fine,” says retired fisheries professor Erol Kesici, who advises the Turkish Association for the Conservation of Nature. “But at what cost?”

Kılıç said it produced in “the cleanest waters in the world” and that Turkish fish farms were among the furthest from land – and subject to regular monitoring.

“As in the rest of the world, there may be opinions that aquaculture activities pollute the sea, but environmental laws in Turkey are extremely strict, implemented and have penal sanctions,” Kılıç said.

Exodus

In Senegal, Aliou Ba, from Greenpeace Africa, says opposition to the factories is starting to cut through. “People are organising, demonstrating and winning battles against industrial interests,” he says, noting that the number of factories has not increased in West Africa since 2019, and Mauritania is cracking down on the use of fresh fish.

Senegalese President Bassirou Diomaye Faye signed a charter for sustainable fishing in advance of the vote last year that brought him to power. The 45-year-old has since boosted transparency by publishing a list of 132 industrial vessels registered to fish in Senegal’s waters. But while the government has promised to better regulate fishmeal factories there is no sign of existing plants shutting down. For fish stocks to recover, the government would need to restrict fishing, compensate communities, and work with Mauritania and Gambia to manage stocks – a degree of cooperation that has proved elusive.

When it comes to fishmeal buyers, Urs Baumgartner, an environmental consultant and academic, insists that the answer doesn’t lie in more certification, which is only likely to ever cover a small slice of the market. Nor is it realistic to replace fishmeal with novel ingredients, such as insects, which have yet to scale, and are likely to bring their own challenges. “If we can’t produce more feed sustainably with the sources that we have, then limit production,” Baumgartner says. “We should eat the fish we catch, not turn it into fishmeal”.

Diaba Diop, who heads up a national network of women fish workers, says foreign companies should source their ingredients elsewhere. “If we continue like this,” she says “the sea will become a liquid desert. When people don’t have enough to eat, we can’t use it to feed animals.”

Back on the Atlantic shoreline, communities are facing another consequence of uncontrolled exploitation: an exodus of young men intent on migrating to Europe. “Instead of being filled with fish, the boats are now filled with people,” notes Cheikh Mbengue, the chief fisherman in Yenne.

Abdou Karim Sall, head of the fishermen’s group in Joal-Fadiouth, sees the neighbourhood emptying in step with the sea. Those who see no future at home risk the 1,500-kilometre boat journey to the Canary Islands, braving a route that claimed over 10,000 lives last year. The sons of women fish traders in Yenne are among those who have gone missing.

“Because there’s no fish, there’s no hope,” says Karim Sall. “The fish should have stayed in Senegal.”

Additional reporting by: Beril Eski, Karen McVeigh (The Guardian), Oscar Rothstein (Danwatch), Hans Wetzels (Follow The Money), Tunca Ilker Ogreten, Mustapha Manneh, Michaela Hermann, and Mike Lewis.

This story is part of a series in collaboration with the Guardian, Danwatch, and Follow the Money. It is part of DeSmog’s industrial aquaculture project.

Endnotes

[1] Estimate takes average weight seabass and bream as 100g or 90g fillets respectively.

[2] Calculated using the following assumptions: It takes 4.5kg of fish to make 1kg fishmeal; an estimate that on average fishmeal in Senegal is made with 80% whole fish/ 20% waste and trimmings; using Eat Lancet dietary recommendations of 10.2 kg fish per person per year.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts