This story is based on investigative reporting first published by Agência Pública.

In a recent Instagram reel, a Brazilian influencer known as “Mylly Biologando” grins at the camera after inspecting a test tube filled with something bubbling and green.

It’s a microalgae that could “transform the future” as a source of less-polluting biodiesel fuel, explains Biologando, whose Instagram name roughly translates from Portuguese as “Biology-ing,” and who’s best known for light-hearted posts about natural science.

Biologando’s trip to the lab, and the video she posted to her half a million followers, are part of a public relations drive to portray the oil company backing the research, Petrobras, as committed to plans that, as she put it, “respect the environment, benefit society, and guarantee the energy that Brazil needs in an increasingly sustainable way.”

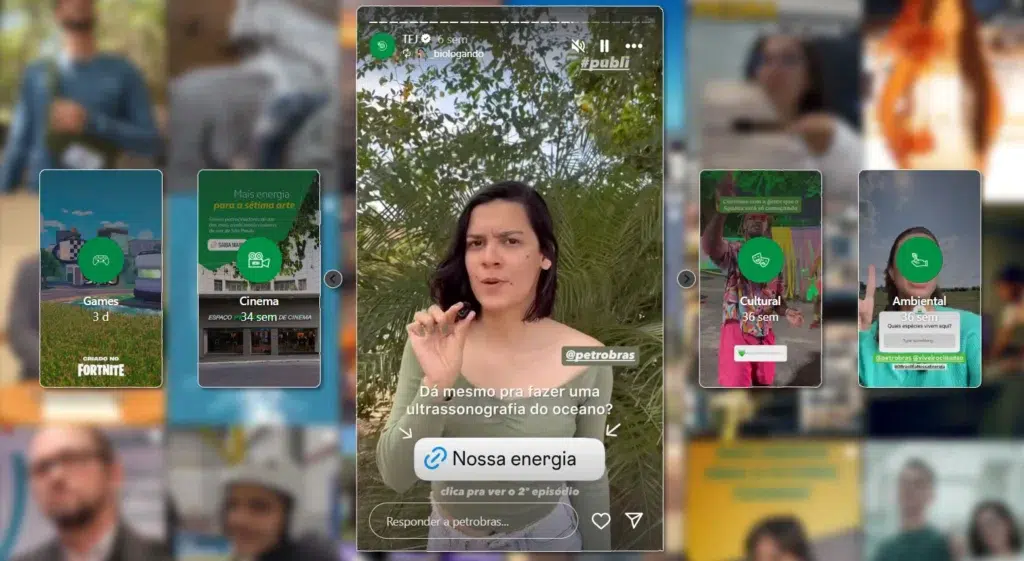

With Brazil gearing up to host the latest round of global climate negotiations, known as COP30, in the Amazon city of Belém in November, Biologando (real name: Ramylly Mirna) is one of a squad of seven Gen-Z science, climate, and culture influencers working to cast Petrobras as a clean energy champion.

In fact, even as climate scientists sound ever direr warnings about the need to slash production of fossil fuels, Petrobras is central to Brazil’s plans to boost oil and gas output by 20 percent by 2030, catapulting the country from the seventh to the fourth-largest oil producer in the world, according to a June report.

Those goals hinge in part on the state-owned oil giant’s plans to invest $3 billion drilling new wells 175 kilometres (109 miles) off the coast of northeastern Brazil — drawing fire from environmentalists, Indigenous elders, and technical experts, who say the move would put an irreplaceable habitat known as the Foz do Amazonas — or Mouth of the Amazon — at risk of an oil spill.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts

Critics also point out that Petrobras’ plans to spend $16 billion on cleaning up its own emissions and researching low-carbon fuels by the end of the decade equates to less than a sixth of its nearly-$100 billion planned investment in fossil fuels.

The company’s attempts to portray algae as a viable climate solution might not necessarily prove very convincing, either. In 2023, the United States-based oil major ExxonMobil — which had famously touted its algal biofuel research as a flagship green initiative — wound down its work in the field, leading many to conclude its experiments had never been more than a PR stunt.

In the light of these concerns, other environmental influencers have accused Petrobras of co-opting the very social media stars who should be helping to expose the company’s greenwashing — not aiding and abetting it.

“Large extractive companies invest thousands in advertising to create a positive public image, which validates their environmentally destructive plans,” said Francisco Figueiredo, a columnist for the independent climate-focused publication O Eco, who said he turned down an offer to join the Petrobras squad. “If they see any value in my profile, it is because they feel I am capable of deceiving people in their favour.”

Figueiredo has little time for peers with fewer scruples. “If they accepted the offer, they either didn’t do any basic research or are ignoring the environmental damage,” he told Agência Pública. “Money spoke louder than any commitment to science.”

‘Brand Loyalty’

In addition to Biologando, the current Petrobras squad includes Francine Oliveira, who’s famous for sharing amusing and thought-provoking placards with a single question, “tell me something interesting” with her 728,000 Instagram followers; Preta De Mais, 214,000 followers on Instagram; Pedro Primak, 353,000 Instagram followers; Yago Stephano, 670,000 Instagram followers; Arthur Bouvie, 136,000 Instagram followers; and Amanda Mota, 344,000 followers.

Since the beginning of June, the squad has collectively racked up over 200 million views for their Petrobras posts on Instagram alone, along with nearly three million likes, according to an Agência Pública analysis. Their videos have also been watched nearly 900,000 times on TikTok, Gen-Z’s favourite social media platform, earning more than 40,000 likes.

A single video Oliveira posted in June, in which she interviews a Petrobras worker — both clad in hard hats and safety-orange jumpsuits — at a natural gas industrial site, has been watched more than 42 million times.

“The more you post, the more you create brand loyalty,” said Laila Zaid, a Brazilian actress and environmental activist with more than 560,000 Instagram followers, who was not part of the Petrobras campaign, “and the more the message is repeated, the more impact it has.”

Prior to its latest campaign, Petrobras has previously worked with influencers including biologist Bianca Witzel, who makes biology “as addictive as your favourite TV show” and has 539,000 Instagram followers.

The goal of these relationships is to get Gen-Zers who are passionate about nature, wildlife, and science to see the company as an ally, rather than a climate and environmental polluter, said Alexandre Costa, a climate scientist and professor at the State University of Ceará.

“You have a sector of society that does not believe in science and lives in a parallel reality, and you have another that keeps its feet on the ground and listens to science,” said Costa. “The oil companies’ use of figures from the world of science to reinforce their propaganda about the energy transition does everyone a huge disservice. It demobilises this second group.”

In response to a request for comment, Biologando stated that her team “carefully evaluate[s] the companies we choose to associate with.” All the information she has posted online refers “to real research that has been taking place at [Petrobras]”, she stated, and “we believe in Petrobras’ seriousness and in its efforts to update itself and prepare for the energy transition.”

Petrobras said that the accusations that it had used influencers to greenwash its image were unfounded, and that its campaign was based on factual information. “The use of influencers is now an established practice in the communications industry, adopted by companies across all sectors that seek to expand the reach of their messages, strengthen dialogue, and connect with different audiences through more accessible language,” the company said.

The other members of the Petrobras squad did not respond to requests for comment.

Money Talks

For influencers, corporate gigs certainly have their perks.

Being part of a squad can involve signing a contract that can lasts from six months to a year, and sets the terms and fees for the total number and frequency of posts, said an ad agency employee who works with Brazilian influencers, who asked not to be named for fear of professional repercussions.

Petrobras declined to respond to a freedom of information request filed by Agência Pública asking for a breakdown of its spending on the influencer campaign, saying that the information is commercially sensitive, and it cannot disclose payments to the influencer squad “for reasons of confidentiality and respect for agreements.”

Nevertheless, the ad agency employee said Instagrammers with 300,000 followers can charge around R$7,500 (about $1,400) for an Instagram story, rising to between R$20,000-25,000 ($3,710-4,638) per post.

The bigger fees almost certainly go to the advertising and public relations agencies who broker the deals.

Propeg, a long-established Brazilian PR agency, and Ogilvy Brasil, part of global ad company Ogilvy, which is in turn owned by UK-based ad giant WPP, both work with Petrobras. The two firms have five-year contracts from 2022 to 2027 with the oil giant that are each worth over R$450 million ($83 million), according to disclosures published on Petrobras’ website, and reviewed by Agência Pública.

In a statement to Agência Pública, Ogilvy Brasil said that it played no role in Petrobras’ work with the influencers. Propeg said that its advertising campaigns for Petrobras are “aimed at broadening dialogue with society across different communication channels, always in accordance with legal parameters and the self-regulation of the advertising sector.”

As part of its services for Petrobras, Propeg created the “#justenergytransition” brand campaign, according to Propeg’s website — which members of the squad have since shared.

‘Worried About Their Image’

While the money might be good, working for the oil industry can come at a cost for influencers — at least in terms of criticism from peers.

“Brands identify profiles [of influencers], maintain a constant partnership, and these people become spokespeople for the company within a specific niche,” said geographer and ecologist Adriano Liziero, who posts about climate at his Geopanoramas Instagram account.

In 2024, Lizerio went viral with a video criticising biologist Átila Iamarino for participating in an influencer campaign for the British oil company Shell. Iamarino did not respond to a request for comment.

In early 2025, Lizerio also slammed recycling campaigner Fernanda Cortez’s involvement in a campaign promoting ethanol for União da Indústria de Cana-de-Açúcar, or UNICA — the Brazilian Sugarcane and Bioenergy Industry Association, a trade group for ethanol and other bioenergy producers in central-south Brazil.

Other influencers who have turned down similar offers have contacted him, said Lizerio, but “I eventually stopped responding, because I felt that some were more worried about their own image than the topic.”

While it can be difficult to discern which companies are ethically safe to work with, Lizerio said that successful influencers could afford to pay consultants to find out.

When asked for comment, Cortez responded that she believes ethanol is the best alternative automotive fuel for Brazil in the short term, “as it does not require a structural change in the [vehicle] fleet. I say this taking into account the research conducted on the impact of fossil fuels versus biofuels, as well as the tight deadline of only five years to reach the 2030 [climate] goals.”

Compared to gasoline, ethanol creates less carbon dioxide emissions, and some ethanol-gasoline blends also lead to lower emissions from evaporation of gas, because ethanol contains fewer volatile compounds. However, growing corn for ethanol has an environmental cost, because it requires large applications of synthetic fertilizer — typically a petrochemical product — as well as herbicides. Using agricultural land to grow corn for ethanol also means that the land isn’t being used for food production.

Other influencers have also pushed back against criticism. Petrobras has previously worked with scientists Ana Bonassa and Laura Marise who post under the name Nunca Vi Ima Cientista (“I have never seen a scientist”). With 776,000 Instagram followers, the pair are known for posting about “science with good humour and credibility.”

In response to a request for comment, Nunca Vi Ima Cientista said that Bonassa and Marise have never been part of a Petrobras influencer squad, and that Petrobras hired them in 2024 solely to host the company’s Nossa Energia (“Our Energy”) podcast.

“The decision to carry out the project stemmed from the understanding that it was a relevant opportunity for two scientists to occupy a space of qualified dialogue on science and technology, expanding science communication to new audiences and, above all, strengthening female representation in science,” the response said.

‘Granfluencers’ and Nail Artists

The oil and gas industry’s growing embrace of influencers is now a global phenomenon.

In 2023, DeSmog reported how fossil fuel giants had used more than 100 influencers to promote their interests worldwide since 2017, reaching billions of people. Participants ranged from a Filippino “Granfluencer” known as “Lola” to a Miami-based nail artist with half a million followers on TikTok.

Promotional material from two PR firms representing Shell boasted of the success of their online advertising. One of the companies claimed that content fronted by a UK inventor reached nearly a billion people, while another claimed that a campaign with a polar explorer made Shell’s audience “31 percent more likely to believe” that Shell is “committed to cleaner fuels”.

In 2020, leaked internal documents from BP showed how the firm sought to “reach influencers” in order to become “more relatable, passionate, and authentic” and “win the trust of the younger generation” — admitting that the company is “seen as one of the bad guys”.

But as Petrobras enlists influencers to shape perceptions online, on the ground in the Foz do Amazonas, the company is facing fierce criticism.

A group that represents communities in the region, Articulação das Comunidades Negras Rurais Quilombolas, or Conaq, has accused the company of failing to consult local people before performing a pre-operational assessment of the offshore drilling site, which the company completed last month.

In a statement, Conaq expressed “deep concern” over the tests and said a lack of democratic and participatory process “highlights environmental racism and the continuation of colonial practices that have historically silenced traditional peoples and communities,” according to a report by O Globo.

“There can be no talk of global environmental leadership or of a just energy transition if decisions continue to be made without the participation of the peoples who safeguard the Amazon and sustain the struggle for climate justice,” Conaq was quoted as saying.

Petrobras told Agência Pública that it was not under any legal obligation to hold such consultations, because it “did not identify direct impacts on traditional communities.” The company said that it has established a “social communication plan…providing for regular meetings with society and communications channels about the oil exploration project in the region, with the goal of keeping stakeholders informed.”

IBAMA, the Brazilian environment agency, has previously denied Petrobras’s requests for exploration licences in the Foz Do Amazonas, on the grounds that the company has failed to present a satisfactory plan to protect the area’s highly sensitive biodiversity in the event of an accident like an oil spill. However, in May IBAMA finally greenlit Petrobras’ latest proposal, despite IBAMA’s own technical evaluation suggesting the plans weren’t sufficient and an oil spill could irreparably damage the region’s unique mangroves and coral reefs.

Campaigners and researchers say IBAMA’s decision is the result of pressure from Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (commonly known as “Lula”), who has publicly declared his support for Brazil to further exploit its own oil reserves, including in the Foz Do Amazonas basin, despite local opposition.

Elle Monielle, a climate and food systems influencer who posts on social media as Ecofada, told Agência Pública that an agency approached her about working on the Petrobras campaign, but she did not respond.

“They wanted me to talk about a fair and sustainable energy transition,” said Monielle, “which I found very ironic given everything that’s happening regarding the Foz do Amazonas and the debate on fossil fuels.”

TJ Jordan and Emily J Gertz contributed reporting to this story.

To read more of DeSmog’s award-winning climate accountability coverage of the advertising and public relations industry, please click here, and visit this database profiling agencies working with fossil fuel companies.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts