Agribusiness companies enlisted an army of Brazilian social media influencers ahead of the United Nations climate summit, now underway in the Amazonian city of Belém, where the meat industry’s surging greenhouse gas emissions and role in deforestation are high on the agenda.

At least 195 influencers — from models and news anchors to doctors and right-wing activists — posted Instagram content sponsored by 10 of the world’s biggest livestock, fertilizer, and food companies in the 12 months leading up to the talks, known as COP30.

That more than doubled the 80 influencers paid to produce sponsored content over the same period a year earlier, according to a DeSmog analysis, which is being published in partnership with Agência Pública.

A version of this article has been published by Agência Pública.

Collectively, these influencers have hundreds of millions of Instagram followers. The content included claims about meat’s health benefits, comedy skits about farming, and music video-style promotions of chicken nuggets and burgers.

Pop star João Gomes posted a video of himself singing and dancing alongside saxophonists after eating a beef burger made by Maturatta, a subsidiary brand of Brazilian meat giant JBS, to his 16.6 million Instagram followers in March.

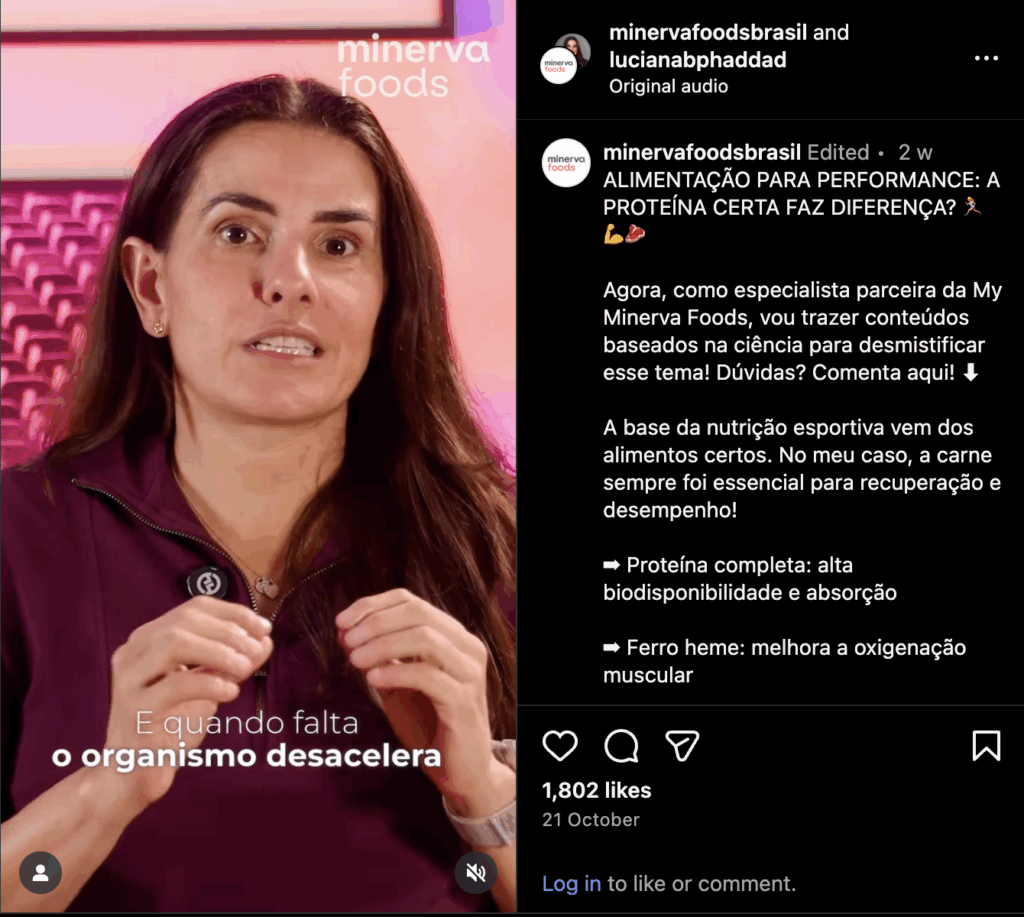

Brazilian doctor and amateur athlete Dr. Luciana Haddad also extolled the virtues of beef, telling her 125,000 Instagram followers in October that she was making “science-based content” for Brazilian meat company Minerva, adding: “In my case, meat has always been essential for recovery and performance!”

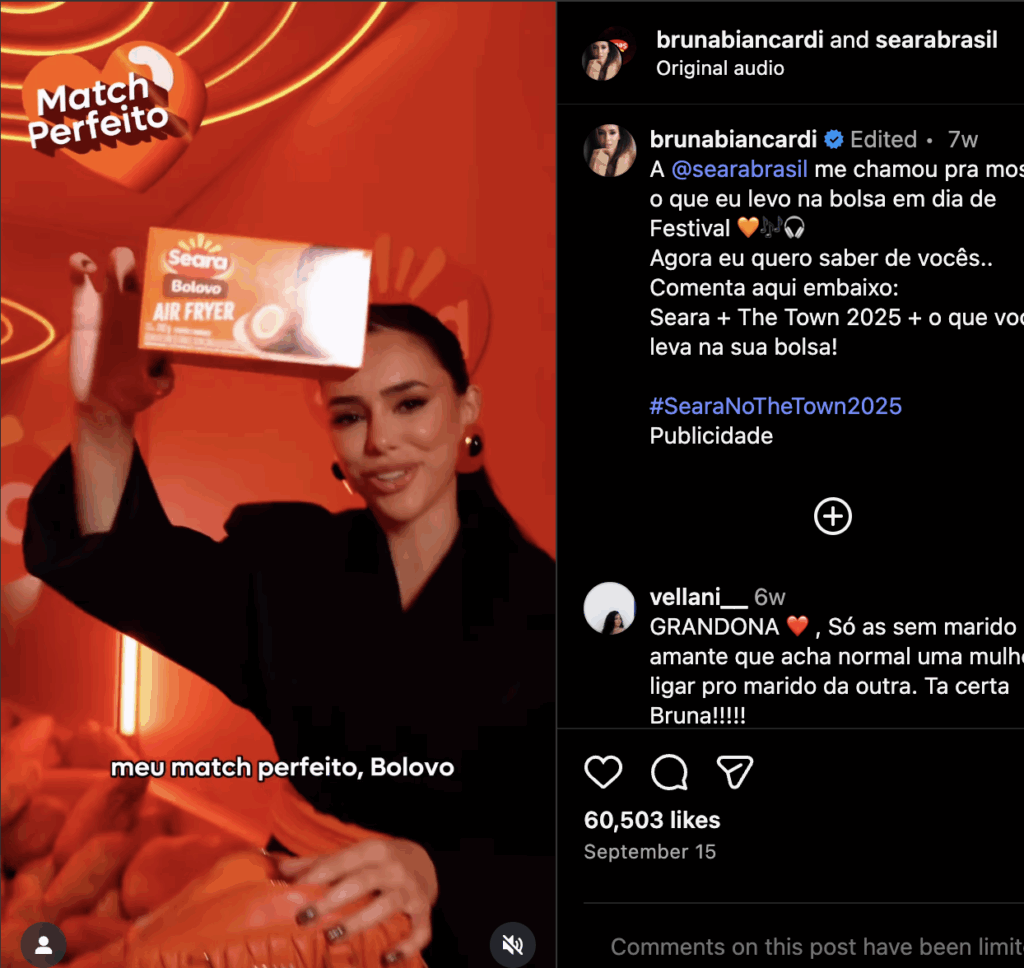

During the “The Town” music festival in São Paulo in September, fashion influencer Bruna Biancardi posted a video of herself opening her designer handbag to reveal fried chicken products made by Seara, a JBS brand, with the caption: “@searabrasil invited me to show what I carry in my bag on festival days.” Biancardi has 14.5 million followers.

Fatima Bernardes, one of Brazil’s most famous news anchors, also posted sponsored content from the festival, receiving more than 100,000 likes for a video she posted to her 13 million Instagram followers, showing herself using an air fryer to cook Seara chicken nuggets.

Influencers often used their reputation or expertise to associate the companies’ products with pop culture or push its supposed health and wellness benefits, rather than directly tackling climate or environmental concerns.

Asked for comment, Haddad replied in an email that “every partnership I make with companies has the same objective: to broaden the dialogue and bring quality information about what really matters for well-being…with Minerva, my content is focused exclusively on my area of expertise, that is, health.”

Biancardi and Bernardes did not respond to requests for comment.

The surge of influencer sponsorships ahead of COP30 did not suprise Eva Morel, general-secretary of the Paris-based media think tank QuotaClimat, which last month published a report on climate disinformation in the French and Brazilian mainstream media.

“It reflects the new strategy of major corporations to legitimize their actions and enhance their reputation — relying on a more human, relatable form of communication that connects with the public and directly influences lifestyles,” Morel said. “The sheer volume, however, is concerning and calls for heightened vigilance from policymakers.”

Brazil’s state oil company also turned to social media to promote misleading messages in the run-up to COP30. A recent Agência Pública investigation (co-published by DeSmog) revealed that Petrobras hired a squad of seven Gen-Z science, climate, and culture influencers to produce content casting the fossil fuel giant as a clean energy champion.

To analyse agribusiness-sponsored influencer content on Instagram, DeSmog used data collected from the ad library of Meta, Instagram’s parent company, as well as searching manually for sponsored content that was not picked up by the ad library. The 10 companies included in the analysis represent the full scope of the global food supply chain, and are at the core of the industrial model of farming: Brazilian multinational JBS, the world’s largest meat producer, and fellow Brazilian meatpackers MBRF and Minerva Foods; global commercial seed and pesticides giants Bayer, Corteva, and Syngenta; European fertilizer multinational Yara; and the U.S.-based agricultural commodities companies ADM, Bunge, and Cargill.

JBS, MBRF, and Minerva, generated the highest volume of influencer content, accounting for three-quarters of the roughly 200 partnerships. However, the biggest increase in the use of influencers was seen among four companies: Bayer, Syngenta, Cargill, and Bunge, which shifted from virtually no influencer content in Brazil to a combined 32 partnerships in the past 12 months.

Seven of the 10 companies increased their use of influencers over the past 12 months. Yara, Corteva, and ADM either slightly decreased their usage or did not use influencers in the past two years.

In response to a request for comment, Syngenta said that it works with influencers to “remain relevant with our stakeholders,” and that “investing in the production of quality information contributes to the strength of science and innovation in all areas, and especially, in agriculture.”

Yara declined to comment for this story.

JBS requested more information about the influencer content mentioned but did not comment. MBRF, Minerva Foods, Bayer, Corteva, ADM, Bunge, and Cargill did not respond to requests for comment.

Climate advocates say that by associating themselves with Brazilian celebrities, agribusiness giants are seeking to distract the public from their ballooning emissions and ward off calls to slash meat consumption in favour of plant-based diets that take a much lower toll on human health, the climate, and the environment.

A 2024 study by public health researchers at the University of São Paulo found that the excessive amounts of red meat consumed daily by the average person in Brazil raises the risk of diseases like cancer, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease. It also far exceeds the “planetary health diet” recommended by the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy, sustainable, and just food systems, which increases plant-based and lowers animal-based proteins.

According to EAT-Lancet’s peer-reviewed October 2025 update, climate-heating emissions from agriculture would drop about 15 percent if consumption of meat, saturated fats, sugar, and salt in wealthy nations decreased, while nutrition-related deaths would decrease by around 15 million a year worldwide — the equivalent of saving more than 41,000 lives a day. These impacts will be even greater if food-related changes extend beyond diets, EAT-Lancet noted: “A food systems transformation is fundamental for solving crises related to the climate, biodiversity, health, and justice”.

Digital Strategy Reinforce Agribusiness Image

The Brazilian presidency hosting this year’s round of climate negotiations has made “transforming agriculture and food systems” objective number three at the climate conference. Agribusiness is likely deploying hundreds of lobbyists, as well as sponsoring events to argue that the industry can address the climate crisis by tweaking business as usual — rather than making the fundamental structural changes that climate scientists say are needed to slash emissions.

Big meat and agrochemical companies’ tactics have included downplaying the industry’s climate impacts, advocating for unreliable technological solutions, and arguing that binding regulation of carbon pollution is a threat to human health and prosperity. [For a guide to agribusiness narratives at the talks, click here —Eds.]

Alternative visions are on offer outside the conference venue at a People’s Summit, where thousands of campaigners, smallholder farmers, and Indigenous activists are calling for a shift to lower-impact farming methods that are more resilient to climate shocks.

Experts are concerned the influx of influencer content could strengthen food and farming companies’ grip on public opinion, making it harder for politicians and civil society to argue for reform. Seven in 10 Brazilians have a positive view of agribusiness, according to a survey published in July 2024 by the Federal University of Pará.

“Regulating online influence has become a key issue for ensuring the social acceptability of the [low-carbon] transition,” said Morel. “Neglecting this matter could undermine the credibility of effective public instruments — starting with the commitments made at the COP.”

Shining a Light on Big Ag’s Climate Push

Sign up to follow DeSmog's reporting about global agribusiness giants — how they're influencing international climate action, and the tactics they're using to sustain a destructive, dangerous and polluting status quo.

Many of the influencers hired by the companies in DeSmog’s analysis, who are among the most popular figures in Brazilian pop culture, were paid to either promote specific products, such as beef burgers and chicken nuggets, or engage specific online communities.

Fitness expert and television personality Marcio Atalla featured in a February video for Minerva, in which he told his 1.1 million followers that meat “is an excellent source of protein, vitamins, and minerals, essential for health, lean muscle gain, and even for the heart!” Atalla also said: “I trust Minerva Foods, which guarantees quality and is committed to sustainability.”

Atalla did not respond to a request for comment.

Agrochemical companies such as Syngenta, meanwhile, chose content creators popular specifically in the agricultural community.

Primos Agro, a channel run by two cousins who make satirical videos about their lives as farmers, posted twice to their 2.1 millions followers in September and October, promoting Syngenta fertilizer products. The videos garnered a combined 280,000 likes.

Although rarer, some influencers did speak directly about climate and environmental issues.

Agribusiness influencer Camila Telles, who regularly speaks at right-wing events and has links to the Atlas Network of conservative free-market think tanks, posted a video for Minerva in June in which she asked her 455,000 followers: “Did you know that the meat on your plate can help the environment?”

Some influencers posted on behalf of both agribusiness companies and environmental organisations. Comedy influencer Fabio Cruz, who posted for the Seara meat brand during The Town music festival in September, posted for Greenpeace Brasil last month wearing a t-shirt that said “Respeitem a Amazonia” (“Respect the Amazon”).

In response to a request for comment, Telles said in an email that “the partnerships I establish exist precisely because my work is already recognized for its serious, coherent, and fact-based approach to Brazilian agribusiness. THEY DO NOT DEFINE MY CONTENT — they only expand the reach of topics I’ve been defending for years, with or without sponsorship.”

Primos Agro and Cruz did not respond to requests for comment.

Brands Increased Advertising Closer to COP30

Influencer content was just one weapon in the advertising arsenal deployed by the 10 companies ahead of COP30.

In the 12 months leading up to the climate summit, they also placed more than 6,000 ads targeted to Brazilian audiences on Google, including around 350 video ads, with nearly half going live in the 30 days before the meeting.

By the end of October, the companies also had a combined 929 ads live on Facebook and Instagram in Brazil. Since Brazilian regulations don’t require Meta — Facebook and Instagram’s parent company — to retain inactive adverts in its ad library, it was not possible to establish whether the companies had increased their ads on these platforms.

Nevertheless, the analysis suggests companies had a particular focus on Brazil. As of 31 October, pesticide firms including Bayer, Corteva, and Syngenta had more live ads on Facebook and Instagram in Brazil than on those platforms in any other countries.

Brazil is the third-largest user of pesticide worldwide, after China and the United States.

Like the influencer content, the ads generally avoided tackling climate change head-on, but served to justify the companies’ existing business models by focusing on the benefits of their products and services.

An ad by Bayer declared, “We continue with the same mission — health for all, hunger for no one,” referring to both its pharmaceutical business and its agrochemicals business.

One JBS ad promoted job opportunities, inviting young graduates to join the company and “feed the world.”

In the United States, the U.S. subsidiary of JBS this month settled a deceptive advertising lawsuit brought by the state of New York. Attorney General Letitia James had sued the company for violating state consumer protection laws by falsely advertising that it would zero out its climate-heating emissions by 2040, after her office’s investigation found that JBS had not yet calculated its total emissions, and had no real plan to back up the promise.

In the ads, JBS USA “used greenwashing and misleading statements” to appeal to consumers’ desires for climate-friendly products, the Attorney General’s office stated in a press release, such as “Agriculture can be part of the climate solution. Bacon, chicken wings, and steak with net zero emissions. It’s possible.”

JBS agreed to pay the state $1.1 million to support climate-resilient farming programs in New York, but said in a statement that its decision to settle “does not reflect an admission of wrongdoing.”

Additional reporting by Ellen Ormesher, Maria Martha, Maria Clara Parente, and Emily J Gertz

CORRECTION (11/17/25): This article has been corrected to reflect that recent reporting into seven Gen-Z influencers hired by Petrobras was based on an Agência Pública investigation.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts