Given radioactive wastewater, earthquakes, and flammable tap water, one might think that drilling and fracking could not possibly have any more dirty secrets. But here’s the biggest secret of all: it’s expensive.

With natural gas at historic low prices – the Wall Street Journal ran a column recently suggesting that the price of gas might even sink to negative numbers, so that producers would need to pay buyers to take it off their hands – it may seem odd to think that fracking is costly. But it’s true. Not just in terms of its environmental footprint, but also in terms of its financial costs.

And everyone should care about how expensive gas is, especially those concerned about energy security and the environment, because the answer will determine the fate of renewables, the way we use land and water, and whether our nation’s energy policies are fundamentally sound.

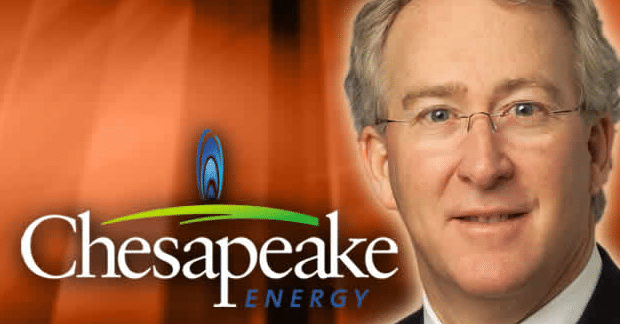

To understand what’s going on, you need to look at Chesapeake Energy, the second largest producer of natural gas in the US, the company described by its founder and CEO Aubrey McClendon as the “biggest frackers in the world.”

For 19 of the past 21 years, the company has operated at what investors call “cash flow negative” – last year by $8.547 billion dollars – meaning that Chesapeake has consistently spent a whole lot more than it earned. For decades.

To fund all that fracking, the company has been flipping land, engaging in so many financial transactions that it’s been said to resemble a hedge fund more than a gas driller.

McClendon’s company has become the environmental Enron, with Chesapeake’s accountants creating some of the most labyrinthine and impenetrable books since Enron, according to some investors.

The company has used all sorts of tactics to cover for its losses and to make fracking look economically plausible even as gas prices have plunged.

This makes figuring out the true costs of the company’s drilling program very difficult. It also means that it’s impossible to weigh the benefits of fracked gas – it may be less carbon intensive than coal as a source of electricity – against the costs, which have been obscured.

An impressive Reuters investigation led a slew of journalists to delve deep into Chesapeake’s books, with each additional report bringing to light more of McClendon’s questionable financial practices as Chesapeake’s CEO.

Without telling investors, McClendon borrowed $1.1 billion dollars to fund his personal 2.5 percent stake in the company’s wells, sometimes from the same banks that lent Chesapeake money, Reuters revealed.

He also was running a $200 million personal hedge fund that trades in the same commodities that Chesapeake sells, and never told investors about that either. He borrowed money from a member of Chesapeake’s board of directors – a person who helps to decide how much McClendon is paid by the company – and again, that was not disclosed.

In short: McClendon used his position as CEO to further his own financial interests. This has the company’s investors furious, and rightly so.

McClendon was removed from Chesapeake’s board of directors – but remains its CEO and is still running the show. Several shareholders have called for him and the entire board to be fired outright over McClendon’s undisclosed personal transactions.

But the problems that should really be raising eyebrows are shown in the numbers that McClendon actually did disclose, according to Reuters. Those numbers reveal that McClendon’s 2.5 percent slice of Chesapeake’s drilling and fracking program have lost hundreds of millions of dollars in just a couple years.

“So right there, it’s just a barometer that tells you, how profitable are Chesapeake’s wells?” Arthur Berman, one of the industry’s strongest skeptics, said on National Public Radio. “They’re not profitable. That’s the takeaway. It’s real simple.”

Others have also raised red flags.

“If they are showing that kind of negative cash flow, the wells don’t have value,” Phil Weiss, a Wall Street energy analyst at Argus Research who was one of the first to ring alarm bells about Chesapeake’s “aggressive accounting,” told Reuters.

In part, what first sparked Weiss’s concern is one of Chesapeake’s unusual financial practices, called a Volumetric Production Payment. These are essentially contracts that let Chesapeake sell its future gas production today. Chesapeake can record income now, and deliver the gas later.

Weiss – and plenty of other market analysts – sees these as off-balance sheet debt, a way for Chesapeake to avoid tallying their actual indebtedness when they describe their finances to investors. The Wall Street Journal reported that Chesapeake has racked up at least $1.4 billion in off-balance sheet obligations from these deals. These sorts of accounting practices are similar to the ones that got Enron in trouble.

They may also mean real trouble for the people Chesapeake owes money to if the company goes bankrupt, because the real assets that Chesapeake has are its wells and its leased acreage. But if the gas from those wells has already been sold to someone else, creditors can’t seize them, according to the Energy Policy Forum, which also points out that the company may be over-producing gas from those wells in order to meet its production targets under these contracts.

So what does all this mean for the rest of us?

First of all, a lot of land, water and clean air – and a lot of money – wasted hunting for a dirty fossil fuel that has been oversold.

When wells are over-produced in the short run, the total amount of gas that can be tapped from the area falls in the long run. So the wells look highly productive today, but this comes only at the cost of future production.

Translation: far more drilling than predicted for far less returns.

The Feds are starting to take a look at some of these concerns. After last summer’s reports, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) launched an investigation into whether Chesapeake and other companies have been over-stating the productivity of their wells or cooking their books.

The SEC is now also looking into McClendon’s potential financial conflicts of interest.

Shale gas has only been in commercial production for about ten years. Many companies have told investors and others that they expect to still be drawing gas from these wells up to half a century from now, which helps to justify spending a lot of money today on drilling and fracking.

But independent analysts say that many wells cannot possibly produce gas for that long, and companies like Chesapeake have been making overly-optimistic assumptions. If the wells fall short, not only are companies in a lot of trouble, but so is anyone who is planning on heating their homes with cheap natural gas or relying on electricity from gas-fired power plants.

Why? Because if the wells underperform, prices are going to rocket upwards and consumers will pay for that.

A lot of problems are beginning to come to light at Chesapeake right now, sending the company’s stock price downward. But the issues extend far beyond just one company.

Drillers have been telling Wall Street investors and Washington policymakers that increased demand will raise prices. In part, that means building plants to export liquified natural gas, turning a domestic commodity into one that can be traded on the world market at higher prices. Those plans have drawn a variety of legal challenges and raised environmental concerns that have stalled expansion. Raising demand mostly means building fracked gas-fired power plants instead of turning to wind or solar energy.

The price of natural gas is artificially depressed, distorting the economic picture right at the time that aging coal plants are being retired. But it cannot stay low forever, especially given the true costs of drilling and fracking that are beginning to come to light.

When the music stops and the price of natural gas spikes, will public utilities have invested in renewables – or will we all be dependent on shale gas that is not only environmentally damaging, but also far more expensive than it seemed?

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts