It’s a commonly held belief, even within the climate action advocacy community, that significant technological breakthroughs are necessary to harness enough clean, renewable energy to power our global energy demands.

Not so, says a new study published this month, which makes an ambitious case for “sustainable sources” providing 95 percent of global energy demand by mid-century.

This new analysis, “Transition to a fully sustainable global energy system,” published in Energy Strategy Reviews, examines demand scenarios for the major energy use sectors – industry, buildings, and transport – and matches them up to feasible renewable supply sources.

Over on VICE’s Motherboard, Brian Merchant dug into the study and put it into proper context.

It is entirely possible, using technologies largely available today, to power nearly the entire world with clean energy—but we need to conjure the will to make revolutionary strides in public policy and the scale of deployment.

His take is smart and thorough, and rather than excerpting him too heavily here, I’m going to urge you to go read his entire piece.

I’ll admit, I opened the report with a bit of healthy skepticism. I’ve been spending a whole lot of time lately buried in EIA and IEA reports while working on an Energy 101 primer. The picture painted by the mounds of energy data and exhaustively-calcuated projections is not a pretty one, particularly as it portrays future demand.

Energy demand, you see, is growing exponentially, and that growth lies at the heart of the great global energy (and climate) challenge. You’d be awfully hard-pressed to find any energy experts out there – even the biggest boosters of renewables – who would argue that we could ever meet future needs with existing renewable technologies alone, if rates of consumption continue as they are.

So I was encouraged to see that this new “Transition” report addresses demand right off the bat. (Emphasis mine.)

The energy scenario we have presented combines the most ambitious efficiency drive on the demand side with strong growth of renewable source options on the supply side to reach a fully sustainable global energy system by 2050. Both are important: the transition cannot be achieved on the supply side alone.

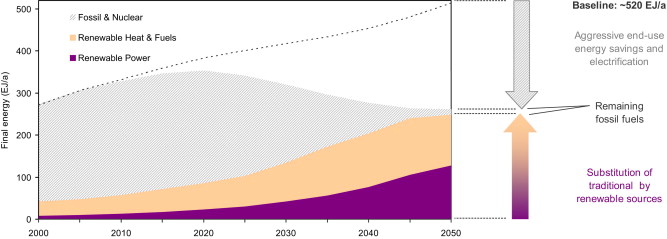

This is key. As is clear in this overview graph from the report, for renewables to provide 95 percent of energy demand, global consumption would have to peak around 2020 and fall over time to levels just below where they were at the turn of the millenium.

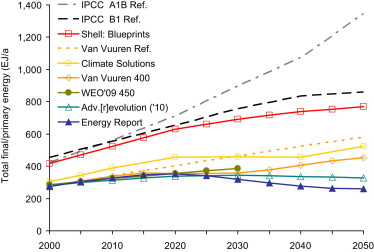

It does have to be said that this is pretty ambitious thinking (and the authors say so themselves). This graph shows the report’s projections next to a bunch of other reference cases, all of which land higher. (A quick aside for the real energy wonks out there: all of this Transition report’s energy numbers are “final energy,” not “primary energy.”)

Fortunately, even these wildly ambitious reductions are possible, and the authors lay out case-by-case, sector-by-sector, how it could actually happen, mostly through efficiency and electrification. It must be emphasized: the drop in energy demand does not involve any consequent reduction in economic activity or quality of life.

It is imperative to understand that the reduction of total energy demand in this scenario is not derived from a reduction in activity. It depends primarily on the reduction of energy intensity through aggressive roll-out of the most efficient technologies.

We’re talking about increased energy intensity in industry (more output per Joule input, you could say). We’re talking about more plug-in hybrids and better batteries and better mass transit service urban hubs. We’re talking about more telecommuting and buildings that don’t leak heat and smarter shipping systems. We’re not talking about shivering in a cold, dark home.

So where will the energy come from?

Even under this ambitious demand scenario, we’re still going to need about 260 exajoules worth of final energy annually to power the planet. Where will it come from, and what do the report’s authors count as “sustainable” energy sources?

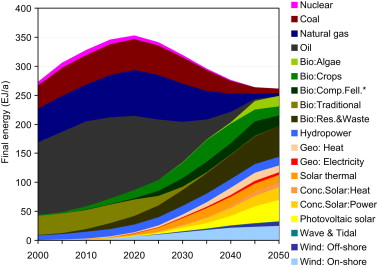

In brief: solar (concentrated heat and power, and photovoltaic), wind (on- and offshore), hydro, geothermal (for heat and power), small amounts of wave and tidal, and a whole raft of bioenergy sources.

Now that, as Merchant put it, “is what an ‘all-of-the-above energy strategy’ looks like.”

What about cost?

Here’s where you – you pragmatist you – start thinking, that looks great, but could we ever afford it?

It’s a worthwhile question, and one you can be sure that the fossil fuel apologists and politicians (plenty of overlap, I know) will be crowing on about. While this report focused predominantly on the “technical feasibility,” and recognizes that it “does not necessarily present the most cost-efficient way of achieving this goal,” it does refer to an accompanying publication that puts the bill at under 2 percent of global GDP during the investment-heavy early years.

While 2 percent of global GDP might sound like a lot, remember that Sir Nicholas Stern’s landmark “Economics of Climate Change” report found that the “overall costs and risks of climate change will be equivalent to losing at least 5% of global GDP each year, now and forever. If a wider range of risks and impacts is taken into account, the estimates of damage could rise to 20% of GDP or more.”

What’s more, the 2 percent of global GDP is a short-term expense that itself pays off in terms of energy costs alone (putting climate aside, foolish as that may be). The Transitions report finds that “in the later years of the assessed time horizon, the net financial impact would be positive, i.e. the energy system proposed in this scenario would be significantly cheaper to operate by 2050 than a BAU system.”

What’s the hold-up?

In short: politics, perspective, ambition.

To achieve such a bold goal we need to combine aggressive energy efficiency on the demand side with accelerated renewable energy supply from all possible sources. This requires a paradigm shift towards long-term, integrated strategies and will not be met with small, incremental changes.

Now long-term thinking sure isn’t our society’s strong suit. If only a report like this was taken as seriously by the media as a totally non-sensical graph and hollow “plan” for “North American energy indepedence.”

Image credit: Shutterstock | James Steidl

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts