Helen Slottje has redrawn the map of fracking in upstate New York.

Since 2010, Slottje and her husband David, both attorneys, have battled to keep fracking out of New York communities using local zoning laws. Since pioneering this novel legal strategy in the town of Ulysses, near their home town of Ithaca, the Slottjes have traveled town to town, helping communities understand language in the state’s constitution that gives municipalities the right to make and enforce these local land use decisions.

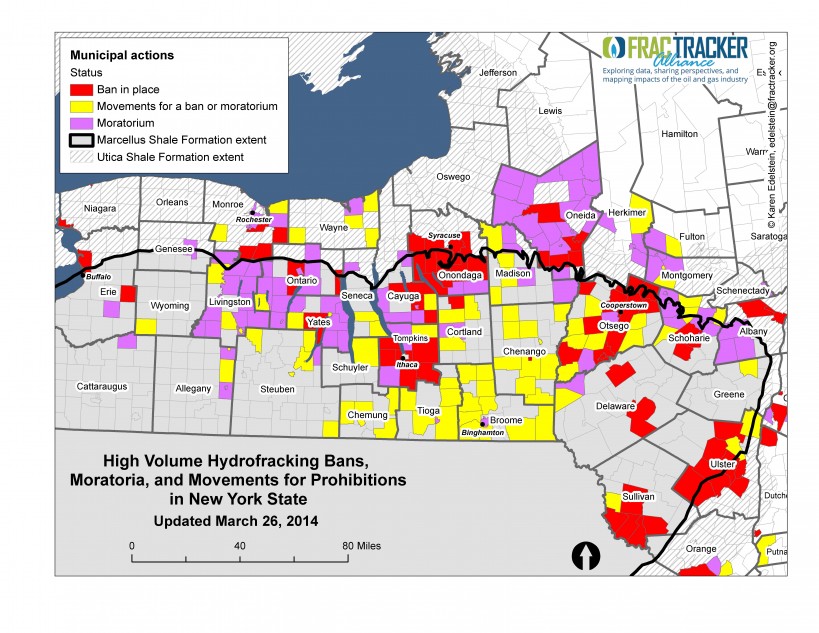

Today, more than 175 communities in New York have fracking bans on the books, so that even if the statewide moratorium on fracking were to be lifted tomorrow, oil and gas companies would be barred from plunging their drills within those municipalities’ borders.

Their efforts were recognized last month with the Goldman Environmental Prize, which some call the “Green Nobel.” The prize committee celebrated Slottje’s pro-bono legal assistance for “helping towns across New York defend themselves from oil and gas companies by passing local bans on fracking.”

Of course, the fracking industry has fought back, challenging the bans in many towns, all of which have been decided in the towns’ favor in the state’s lower courts. Two cases, in the towns of Dryden and Middlefield, are up before the Court of Appeal which will hear oral arguments on June 3 in Albany.

DeSmogBlog spoke with Helen Slottje about how she got into the fracking fight, how to talk about fracking to communities that are being promised so much wealth by industry, how to go face-to-face with big oil and gas flacks, and what lessons could be learned from the success of the town bans for other battles against the fossil fuel industry. The hour-long conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You weren’t always practicing law in the public interest. What brought you to the fracking fight?

My husband and I were both corporate lawyers in Boston. I graduated from law school in 1992, and started off working on failed banks. As the economy turned, I started working on commercial real estate deals.

I grew sort of weary of the practice of law, started finding it sort of dehumanizing. When we moved out here to Ithaca it was a gradual transformation from Republican consumerist to, well, an Ithacan.

And then we learned of fracking, and there was a sort of defeatist attitude — everyone was saying, well we can’t really do anything about it. And we thought, sure we can.

So that’s where your former practice came in handy?

As a corporate lawyer you never say you can’t do anything about it. It’s not an option. You always find out some way to figure it out, to get done what your client wants done.

If you want to keep in the practice and keep your clients happy, you don’t tell them no.

Most environmentalists and activists are generally very nice people and take others at face value and don’t imagine people would lie to them or mislead them.

But that’s just not how the corporate world operates.

You go for the jugular if you can. You basically look at every win for the other side as something that came out of your pocket.

So with that background, when we learned about fracking, heard that there was nothing we could do, we sat down and explored every possible avenue for how we could fight this.

And you found one avenue that seemed to work.

We call them “bans” and they’re based on town zoning laws. The legal theory is that towns can use zoning and land use laws to prohibit gas drilling.

This hard-line legal approach is something that other people hadn’t really done.

Just as importantly, as former corporate lawyers — with a committed to winning, whatever it takes approach — we were used to being hard-charging and working long hours, so we didn’t really take any days off and worked with everyone. We were going to town meetings at night all over the area almost every night.

We started in a couple of towns, getting the bans passed, and now 175 to 180 towns have passed something.

Credit: FracTracker

Wasn’t that corporate background and the aggressive attitude a tough sell in some of these communities? And even with your potential allies?

Almost all of the activists we work with come to appreciate the aggressiveness, even if they aren’t personally comfortable behaving in a corporate fashion. They are happy to have someone out there doing it.

In some of the communities, especially those that have been promised “streets paved with gold,” it can be hard negotiating and reaching those people. For some towns, it helps to send out David, who looks like Dick Cheney if he looks like anybody. David is as conservative as I used to be, so when he goes in and talks to these town boards, they listen.

But putting the messenger aside, the message resonates?

Pretty much anyone who we describe as a “good faith neutral” — which is someone who really doesn’t stand to make a ton of money from fracking and is open to objectively figure out what’s best — after you present them with our argument, almost invariably, they think that it’s appropriate to put a halt to this fracking.

The people who tend to disagree with us are really large landowners who basically have taken the public position that they’re trying to save the family farm. But fracking doesn’t save the family farm. It’ll ruin it.

But a lot of those people are looking for the lottery ticket. They say ‘fine, frack it. I’m going to get out of here. I’m going to head to Florida.’ They’ll go retire someplace where there isn’t fracking.

So there’s no talking to those people. They’re not persuadable. For psychological reasons, they’ll only listen to things that fit what they already believe.

But those people are really a very small minority, though they often do control town boards.

There was an interesting sociological study in the town of Candor. It found a tension in rural communities between the new arrivals, and the old farming families. A compact is informally reached, with the new arrivals saying “we’ll let you run the town” to the big landowners and the old farming families.

So there’s a disproportionate level of big farming landowners on town boards, in control of town boards. Which, historically, wasn’t super important.

But now we’re in the position where we have these incumbents who have been in office forever, and they’re pro-fracking because it benefits them as large landowners. And it’s very hard to replace those people in elections because you’re trying to change the whole social order of the town.

It’s very difficult. So in some of those towns, it’s unfortunate, but we can’t make a lot of progress there.

So focusing on the so-called “good faith neutrals” then, what message do you deliver?

First of all, we never mention climate change. Because there are people who will tell you that they “don’t believe in climate change.” So despite the fact that we of course believe in climate change and believe that fracking is a terrible contributor, we specifically do not talk about climate change.

Instead, we talk about how the burden should be on the frackers to show that it is safe, and not on the community to prove that it isn’t safe. That makes sense to people. So we focus on the fact that industry can’t prove that fracking is safe. If they could prove that fracking was safe, then we could all relax. That’d be great. But it isn’t, so we can’t.

We don’t like to get too bogged down in the technical details either. You lose people. You don’t need the know about Darcy’s Law and hydrogeology. It’s about dust and chemicals and truck traffic. So we really focus on traffic and community character and noise and dust.

We use a lot of quotes from industry and unpack them. The CEO of some energy company says something like, Yes, there’s going to be traffic. We’re going to tear up your roads and there’s going to be dust and it’s going to be dirty. Deal with it. You put that up on a slide and it offends people, this arrogance of industry.

Another thing that is really helpful is paying very, very close attention to the words and exact phrases that industry uses. You don’t know where to look for industry’s weaknesses until you carefully examine their language. We look for words of limitation in their disclaimers. You can turn around what they’re saying to figure out what they’re hiding. Yes, natural gas might be “cleaner burning,” but it’s not “cleaner.”

Helen Slottje speaking in Cooperstown. Credit: ShaleShock Media

Are you able to point across the border to the unkept promises in Pennsylvania?

Yes, though the people who are pro-fracking don’t think anything bad has happened in Pennsylvania and you can’t convince them otherwise. They think that everyone who has said they have water contamination is lying. They say it’s just small landowners who are jealous of large landowners.

And what about the families getting screwed out of royalty payments?

They tend to think that’s not going to happen to us. They’ll say, We’re going to get a better lease. We’ll have a better lawyer. You’re going to have a better lawyer than industry has? No way. You’re going to have more lawyers and more resources to fight them? It’s not even possible. At the end of the day, it doesn’t even matter what the contract says.

But they’re blinded by the promise of riches. They’ll look at the one person in Pennsylvania who has won the lottery and that’s all they see.

At DeSmogBlog, we do a lot of work on the fossil fuel industry’s “PR pollution.” Do you deal with any of the front groups face-to-face?

There are a few local people with NaturalGasNow. For awhile they went to every meeting we were at, filmed us and proudly told the town boards that they were recording footage for whenever the town was ready to sue us.

They flip flop with their criticism of us. Either we’re rich transplants that don’t need the money, or we’re desperately trying to get more clients. They can’t seem to fathom that some people would make sacrifices.

Helen and David Slottje. Photo credit: Photo: Matt Richmond, Innovation Trail

If you’re in it for the money, you clearly chose the wrong side.

They’ll say that we’re trying to get more clients, but our clients don’t pay us. So, yes, we want more clients, but a lot of nonpaying clients doesn’t make you rich. Doesn’t even make you a living. Just more work for us.

The real gig would be to go out and talk a big game and not really do anything. To pretend we’re a big green environmental group.

But instead we do a terrible job fundraising, we do a great job working for our clients just trying to get stuff done. And I can assure you we are not getting rich doing this. We spent a lot of our retirement savings funding the town ban efforts early on.

Would you have any advice for others working on the ground who find themselves up against the industry PR machine?

It’s tough because they’ll go right after people. They will target individuals and try to humiliate them, mostly because that does intimidate people from speaking up. So a big part of it is just being prepared for that. Knowing that it might happen. If you’re expecting the smear, it’s less devastating than if you went in naive and thought that everything would be civil.

In most towns there’s a relatively small group of people who stay committed, and it’s the same people coming to these meetings month after month. It’s easy to get the feeling that you’re not getting any traction, not gaining more supporters.

But I think these meetings serve a very important purpose even if you’re not attracting more advocates. They remind people that they’re not it in alone, and ultimately those efforts wind up paying off.

Anti-fracking rally at State Capitol, Albany. Credit: FoodandWaterWatch.org

Do you and David have any ambitions beyond New York?

We’re only admitted in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Texas, and New York, so we can’t practice anywhere outside of those states. But we’re talking to attorneys in other states to advise them on what they can do. Fracking is in play in California right now, so we’d like to help there if possible. We’re working on getting admitted in California to help to whatever extent is needed.

We try to figure out the best ways to leverage what two people can do. We were slowly working on the New York ban movement, as nobody else had touched that and it was vital that we were out there working on it, and showing people that it could be done.

And now there are 175 towns that have, and it’s before the Court of Appeals so we’re going to have a decision one way or the other. So while we’re going to want to finish up with some of the towns that are in the pipeline, we’d really like to work with groups on other types of projects — like infrastructure build out.

So could these types of zoning and land use laws potentially be used not just for drilling and extraction, but for pipelines and other infrastructure? To potentially ban trains and pipelines from carrying oil and natural gas through cities and towns?

The laws aren’t specific to drilling, but they are subject to state regulation. Those pipelines are approved by FERC, and federal law trumps state and local law, and there’s a whole interstate commerce issue with railroads and pipelines.

Frankly, FERC doesn’t do its job determining whether the pipeline will do its job or not or whether the pipeline should be built. Their attitude seems to be that every pipeline is a good pipeline, and the more pipelines the better. They’ll tell you straight up: we’re a permit approval agency. We’re an infrastructure agency. That’s what we do. We approve and build infrastructure.

So that’s tough to stop with local laws.

On the legal side of things with the fracking bans, what are the implications of the Court of Appeals hearings?

The question before the Court of Appeals is: can towns use zoning and land use laws to prohibit gas drilling? And if the Court of Appeals were to say “no” then the industry will get a very broad clean slate on zoning issues.

But if the court upholds these laws, which we think is more likely, then there will be a big green light for towns to proceed in doing this, with a broad legal approval of these actions.

You sound confident that the Court will uphold these laws.

So, you’re looking at these cases as a non-lawyer, looking impartially, and trying to figure out what will happen. Industry is saying all the things you expect industry to say, and lining up amicus briefs from API (American Petroleum Institute), the Chamber of Commerce, the Rocky Mountain Legal Fund. And on the town’s side is everyone you’d expect: NRDC, Riverkeeper, Sierra Club…every environmental group you’d expect is chiming in.

But in the middle, there’s a group of 13 of the leading zoning and municipal law professors in the country, many of whom are from New York. And they have come out in favor of the towns. These law professors aren’t biased like we are. All they want is good law. So that makes a very compelling case, as the law is very clear here.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts