Two oil companies planning to drill in remote Arctic waters, Shell and ConocoPhillips, are pleading with U.S. regulators not to make them follow new guidelines proposed by the Interior Department that would require the companies to keep emergency spill response equipment close at hand and prohibit the use of chemical dispersants.

The precise details of the new rules for Arctic drilling operations have not been made public as an inter-agency review of the Interior Department’s proposal is still being carried out.

But records of meetings with officials at the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), which is currently reviewing the new standards, show that Shell is vigorously contesting rules that would require the company to keep on hand the necessary equipment for emergency response in the event of a blowout, such as containment systems and a rig to drill a relief well.

Shell says that keeping a rig on standby would cost the company an additional $250 million a year.

Both Shell and ConocoPhillips are taking issue with another of the proposed rules, a potential ban on the use of highly toxic chemical dispersants in favor of booms, skimmers, and other physical equipment to contain spilled oil.

In a presentation to the OMB‘s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, Shell argued: “A 100 percent mechanical requirement leads to increasing costs and environmental impacts — less recovery of oil — as operators enter plays with higher daily worst-case discharges.”

Studies have shown that while dispersants can help prevent oil from washing ashore and may protect surface-dwelling sea life, it can have serious impacts on marine life living below the surface.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office says that very little is known about how quickly these chemical dispersants biodegrade, especially in frigid Arctic waters, and has called for more research.

According to Fuel Fix, “The six Chukchi Sea wells Shell wants to drill have estimated worst-case discharges ranging from 8,700 to 23,100 barrels per day.”

Environmentalists are quick to point out that emergency preparedness is especially crucial in the harsh Arctic environment since winter sea ice cover would put a halt to any spill response measures, allowing oil to spew freely for several months. And given its remote location, there are not existing emergency response facilities, equipment, and teams in the region.

A comparison is often made to BP‘s Deepwater Horizon well blowout and oil spill, which occurred in the far more temperate waters of the Gulf of Mexico. That blowout still took 87 days to cap, and cleanup efforts continue to this day.

As Marilyn Heimann, director of the U.S. Arctic Program for Pew Charitable Trusts, told Fuel Fix: “it took months in the Gulf to drill a relief well, and they were not contending with extreme cold, darkness, high seas and ice.”

Some 6,000 ships were used to skim BP‘s oil in the Gulf, according to Greenpeace, while Shell’s oil response plan for the Chukchi Sea lists only 9 ships.

BP‘s use of chemical dispersants to clean up the spill was highly contoversial — “the dispersants contain harmful toxins of their own and can concentrate leftover oil toxins in the water, where they can kill fish and migrate great distances” — which is no doubt fueling today’s wariness of using dispersants in the Arctic.

Greenpeace argues that the risk inherent to drilling in the Arctic is not worth the reward:

A Three year fix – the US Geological Survey estimates the Arctic could hold up to 90 billion barrels of oil. This sounds a lot, but that would only satisfy three years of the world’s oil demand. These giant, rusting rigs with their inadequate oil spill response plans are risking the future of the Arctic for three years worth of oil. Surely it’s not worth taking such a risk?

Shell had already begun exploration activities in the Arctic in 2012, but was forced to call them off after its Kulluk drilling rig ran aground, costing the company $200 million. Shell has filed a new exploratory drilling blueprint with the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management that would have the company return to the Arctic in summer of 2015.

There’s no word on when the Interior Department’s new Arctic drilling regulations will be finalized and take effect, though a draft is expected to be made public later this year.

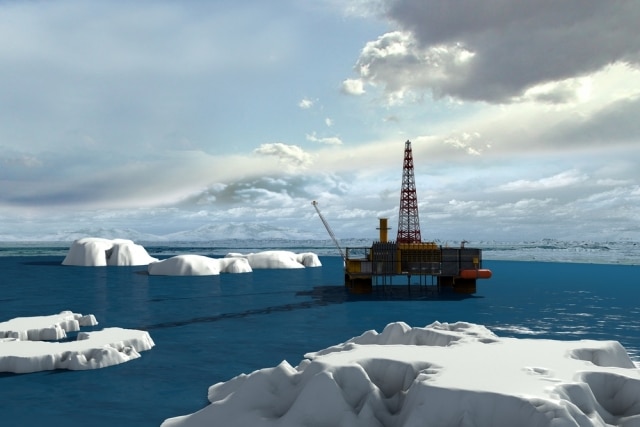

Image Credit: Oil platform in the Arctic Ocean, the oil production by vitstudio / Shutterstock.com

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts