As politicians from oil-producing states work to draw up bills to end the ban on oil exports, Mexican officials are “confident” that the country will soon be importing American crude through a backdoor loophole in the law.

Back in January, Mexico applied for a crude swap that, if approved, would allow the U.S. to export 100,000 barrels of oil per day to Mexico. This would be unrefined crude — refined products such as diesel and gasoline are not subject to the ban — likely from the Eagle Ford and Permian shale fields, where fracking has produced a glut of light, sweet crude in recent years.

Though the crude oil export ban has been in place for about four decades, it allows for certain exemptions to be permitted. Exports to Canada, for instance, are allowed, so long as the oil will be processed and consumed in Canada. And last year, Commerce Department officials in the Obama administration approved the export of condensate, an extremely light and gassy form of oil that can be minimally processed in the field without any trip to a refinery.

Condensates are already flowing heavily out of Texas shale regions, and since permission was granted last November, there’s been a rush of condensate exports to Mexico.

If the crude swap is approved, it’ll open up another loophole to the export ban for crude to flow through.

Very few exceptions have been made to the ban since it was implemented as a response to the Arab oil embargo in 1973. Exports are allowed to Canada “for consumption or use therein,” and very limited exports are allowed from Alaska.

Last September, Alaska shipped off its first crude export in over a decade.

Exceptions to the Rule

Under the Energy Policy and Conservation Act, crude can legally be “exported to an adjacent foreign country to be refined and consumed therein in exchange for the same quantity of crude oil being exported from that country to the United States; such exchange must result through convenience or increased efficiency of transportation in lower prices for consumers of petroleum products in the United States.”

In other words, it can be swapped for an equivalent amount of crude or refined product and the exporting companies must prove that it’s in the national interest and that there are legitimate economic or technical reasons that the exported crude cannot be sold domestically.

All we know about the proposed exchange has come from Mexican officials, as the Commerce Department has been silent on the issue.

Comments from Pemex officials earlier this year reveal that Mexico is proposing to send heavy crude north across the border in “exchange” for light, shale-sourced crude from the US, and that they are “confident” that the exchange will be approved.

In theory, it looks like a pretty fair exchange. But what of the fact that the U.S. already imports a significant volume of crude from Mexico?

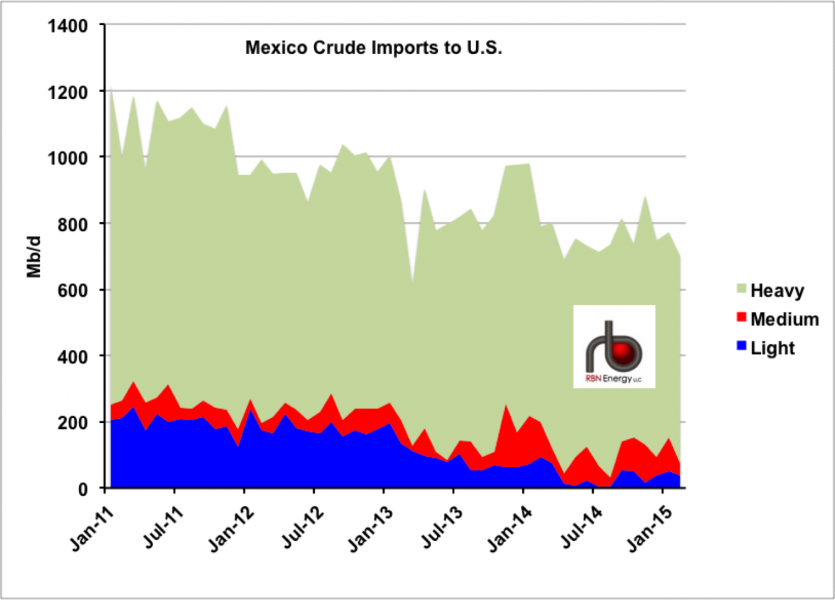

This chart from RBN Energy, using data from the Energy Information Agency, shows that the U.S. is currently importing roughly 700,000 barrels per day of crude from our neighbor to the south, much of it the heavy crude that Pemex is offering to “swap” for our light shale oil.

In fact, Mexico is already the third largest exporter of crude to the U.S., consistantly sending America more than even Venezuela.

Many Gulf Coast refineries have been retrofitted over the past two decades to handle heavy crude, so there certainly is demand. (Especially so considering that most of the crude flowing from the newly drilled shale wells is lighter.)

But, crucially, there already appears to be unfettered access for these refineries to that heavier product. From a demand standpoint, there’s no need for a swap because there is no obstacle to importing the heavy crude.

Can something be legitimately considered an “exchange” if one side already has full access to the goods offered in the swap?

If the Obama administration, through the Commerce Department, approves this exchange, it won’t be because the U.S. is in desperate need of better access to Mexico’s heavy crude.

Rather, it would be a gift to the companies fracking the shale fields and pumping out a glut of light oil with a shrinking domestic market.

Oil companies and their allied politicians will argue that the economic boon of keep the fracking bonanza alive is in the national interest.

Landowners and citizens in towns and counties ravaged by fracking might feel differently about the public benefit of drilling and despoiling American land to ship a little desired product abroad.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts