A version of this article appeared in The Guardian.

In early September, the Danish climate crisis denier Bjørn Lomborg travelled to São Paulo to deliver a stark warning. On the sidelines of a conference called the Forum Caminhos da Liberdade, happening just as Brazil was gearing up to host annual global climate talks (known as “COP30”) in November, Lomborg claimed that if implemented poorly, government efforts to address climate change could “destroy economic growth.”

Lomborg had some behind-the-scenes assistance to help his message land, because one of the top 2025 sponsors of the conference (whose speakers in previous years have included Silicon Valley billionaire and Donald Trump ally Peter Thiel), was Atlas Network, a United States-based worldwide coalition of more than 500 free-market think tanks and allied partners. This wasn’t the first time that a foreign conservative activist aimed to stir up doubts in Latin America about climate action on the eve of global climate talks.

Starting in earnest around 1997, during the early years of United Nations-led efforts to forge a global climate pact, Atlas Network and its partners created and executed a playbook to sabotage support for international treaties across the Global South, according to hundreds of Atlas Network documents obtained by DeSmog.

A key early funder of this strategy: ExxonMobil.

It’s now public knowledge that throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Exxon helped fund and lead a constellation of U.S.-based organizations that sought to discredit climate science, assure the public that it was safe to burn fossil fuels, and block America’s participation in the international climate treaty — a campaign that is now the subject of dozens of lawsuits across the U.S. accusing the company of deceiving the public.

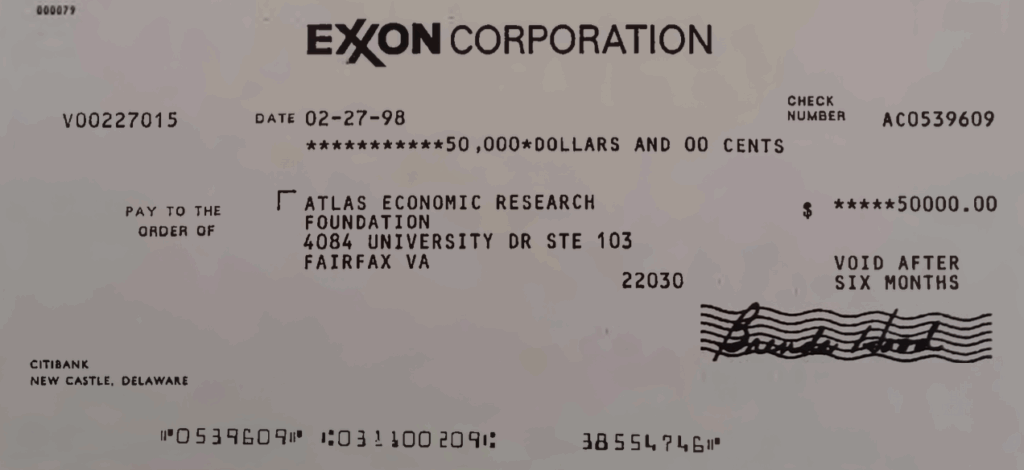

DeSmog’s newly obtained documents, which included copies of checks mailed to Atlas Network for amounts ranging from $15,000 to $50,000 at a time, show that Exxon, with the help of Atlas Network partners, was also quietly financing climate denial in developing countries.

These strategy memos, funding proposals, personal letters and progress reports reveal in specific detail how Exxon and Atlas Network (which was formerly known as Atlas Economic Research Foundation) sought to amplify diplomatic tensions ahead of climate treaty summits, which are focused on bringing countries with vastly differing economic and social needs to consensus on reducing carbon emissions.

In stoking confusion and doubt about climate change among developing nations during critical early moments of climate diplomacy, Exxon and Atlas Network exacerbated geopolitical fault-lines and raised economic fears that persist to this day, according to Kert Davies, director of special investigations at the non-profit Center for Climate Integrity, who is a long-time expert on Exxon’s climate denial campaigns.

“That’s a pretty ugly history,” Davies said. “Exxon seemed to think that if you could make developing nations, and all nations, skeptical that climate change was a crisis then you’d never have a global climate treaty.”

The checks Exxon wrote to Atlas financed activities ranging from Spanish translations of English-language books denying the reality of climate change, to flights to Latin American cities for U.S. climate deniers. They funded public events that enabled those deniers to reach local media and network with policymakers, as well as Atlas Network partner reports warning of dire economic consequences from climate policy.

The goal was to make countries across the region “less inclined” to support treaties on cutting carbon emissions, even though these agreements would be essential to stopping global temperature rise from spiraling out of control.

Three decades later, the consequences of insufficient global climate action are impossible to ignore. Scientists announced in mid-October that worldwide carbon emissions are so high that the planet has passed the tipping point where a mass die-off of the planet’s coral reefs is likely irreversible, and that unless there are drastic global cuts to emissions and deforestation within the next 10 to 20 years, a collapse of the Amazon rainforest could be locked in.

‘Never an Important Donor’

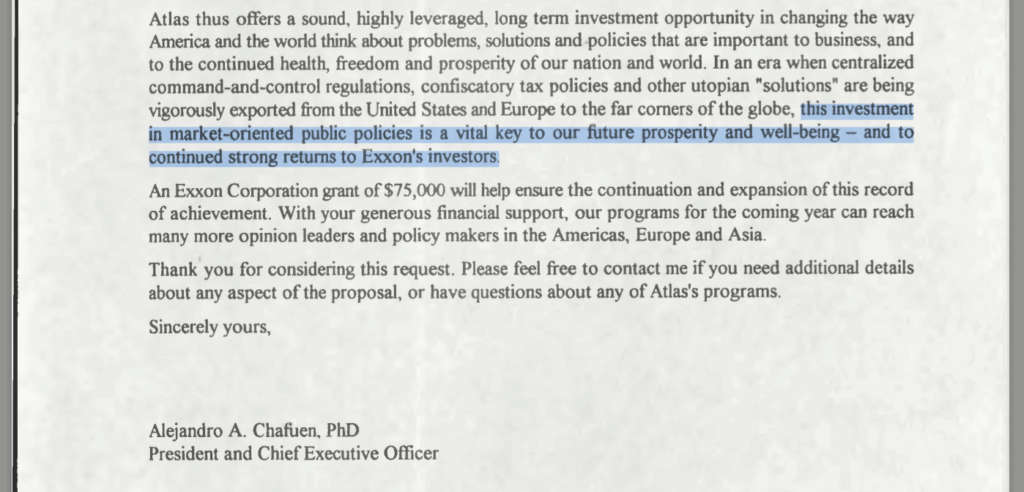

Exxon’s climate obstruction in the Global South had the potential to increase profits, according to a 1997 strategy plan “dealing specifically with the problems of international treaties” that Atlas sent by mail to the company’s headquarters in Irving, Texas. “This investment in market-oriented public policies is a vital key to our future prosperity and well-being — and to continued strong returns to Exxon’s investors,” Atlas Network explained.

Asked about this document and others viewed by DeSmog, Atlas Network spokesperson Adam Weinberg replied that “these questions deal with memos and materials drafted by former employees from more than a quarter century ago, addressed to a corporation that was never an important donor to our organization, and which indeed has not been a donor at all for close to two decades.”

But considering that over 50 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions since 1751 have been released since the early 1990s, Exxon and Atlas Network efforts to stall carbon cuts are extremely relevant to where the world finds itself today.

“What happened 30 years ago matters very much,” said Carlos Milani, a professor of international relations at Rio de Janeiro State University’s Institute for Social and Political Studies. “The atmosphere has a huge historical memory when it comes to greenhouse gas emissions.”

Exxon did not respond to a request for comment.

‘Influence Government Policies’

During his September trip to Brazil, in addition to attending the Forum Caminhos da Liberdade, Lomborg gave a lecture at a private research university in Belo Horizonte known as IBMEC, which he later said in his newsletter was “broadcast to hundreds of students unable to fit into the auditorium.”

Lomborg had been described in Brazilian promotional materials as one of the world’s leading experts on environmental issues and other global challenges, even though many actual climate scientists regard his statements on climate change as misrepresentative of the mainstream consensus that global temperature rise is an urgent and escalating crisis.

Lomborg did not reply to detailed questions about his activities in Brazil. The university event was hosted by IBMEC professor Adriano Gianturco, who is a board member of the Instituto Liberal, a Rio de Janeiro-based think tank and Atlas Network partner with a history of spreading climate disinformation throughout Latin America.

In videos posted to social media during the summer, Instituto Liberal repeated in Portuguese the long-standing climate denier trope that COP30 is an expensive get-together for the United Nations’ globe-trotting technocratic elites that will leave nothing but debt for ordinary Brazilians.

Instituto Liberal did not respond to a request for information. “We did not convene any of the meetings or activities with Bjørn Lomborg,” Weinberg of Atlas Network said in email. “We do not take institutional positions on topics like COP30.”

Instituto Liberal has been fine-tuning its critique of the international climate treaty process since at least 1997, when it was contacted by Atlas Network about “an important new donor” looking to foster think tanks in the Global South.

The proposal explained that the donor was particularly interested in “international treaties and agreements that force Latin and other developing countries to adopt stringent labor, environmental or other laws that may not reflect the developing nation’s own needs, priorities or viewpoints on these issues.”

That donor was Exxon, which — as detailed in a 1997 letter from Exxon executive William Hale to Atlas Network — was “interested in nurturing free-market think tanks outside the United States,” particularly in Asia, the former Soviet Union, Europe, and Latin America. Exxon was prepared to give Atlas “up to $50,000” — adjusted for inflation, roughly $100,000 in today’s money — to grow “international groups which have the ability to influence government policies.”

In a 1998 letter to Exxon’s Hale, then-Atlas Network president Alejandro Chafuen spelled out how its partner organizations could amplify the company’s influence in the Global South. They would provide “entrees to government officials”; “access to local and national TV and radio programs”; “a distant early warning system on emerging issues”; “an improved ability to respond to legislative and regulatory initiatives”; and, “a greatly expanded ability to carry corporate messages…beyond Washington and the United States.”

Latin American academics who study Atlas Network see in such activities a coordinated effort to create favorable political conditions for big business and foreign investors. “It is a movement,” Ana Lúcia Faria and Vera Chaia wrote in a 2023 paper, “to legitimize and pave the the way for the unbridled escalation of capital.” The research was published in the London Journal of Research Humanities and Social Sciences.

Atlas Network in its 1998 funding proposal to Exxon stressed “that even relatively small investments in developing nations can produce substantial results.” The proposal explained that Exxon funding would “enable new and established think tanks to undertake or expand studies of vital importance to business in general and the petroleum industry in particular.”

In March 1998, Exxon mailed a $50,000 check to Atlas Network.

‘Adverse Consequences’

Exxon’s financial support of Atlas Network came at a crucial early moment in global climate diplomacy.

World leaders had met in Japan in 1997 to negotiate the Kyoto Protocol, the first-ever legally binding international treaty designed to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions.

Over two weeks of negotiations, tensions surfaced about which countries should bear the costs of addressing the mounting climate crisis. The wealthiest nations had created most of the climate-heating pollution over two centuries of coal- and oil-fired industrialization, but emissions from developing nations were rising in the present as they industrialized their economies and pulled their citizens out of poverty.

Countries were planning to convene in Buenos Aires in November 1998 to find a solution that could help unite the Global North and South more decisively in the worldwide climate fight. It would be just the fourth annual “conference of the parties” to the United Nations climate treaty process, thus known as “COP4.”

To Atlas Network, this meeting would be “a rare opportunity” to create opposition to the Kyoto Protocol for those “who doubt the claims behind the global warming theory, and worry about the devastating results that any treaty could have on the United States, the world economy and the energy industry.” With Exxon’s support, Atlas Network believed it could help persuade the developing world of “the adverse effects of global climate change treaties.”

In September 1998, just two months before global delegates were due to meet, Atlas Network requested supplementary financing from Exxon to fund a series of global warming seminars. The money would pay for Atlas Network to fly Patrick Michaels, a U.S. climate denier, to Buenos Aires to speak at the events. Michaels was connected to several think tanks and groups that had previously received money from Exxon,

Earlier that year, Michaels had erroneously stated in a short film that “the entire global climate change hysteria is driven by computer models; it is not driven by reality.”

Atlas Network pitched to Exxon that the additional funding would also help several think tanks in the network facilitate meetings between Michaels, as well as other seminar speakers, and “ministers, politicians, editorial boards [and] business leaders in Argentina.”

This wouldn’t be difficult to organize, as Atlas Network had explained to Exxon in an earlier funding proposal, because “the many free market think tanks in Argentina, Brazil and other Latin countries enjoy excellent relationships with the news media and high level government officials.” Those think tanks, in turn, were also connected to “bankers, owners of investment funds, and party advisors,” according to Brazil-based researcher Hernán Ramírez.

Further, the extra money from Exxon would pay for analysts at Instituto Liberal and other Atlas Network think tanks in the region to produce a report about the “trade, economic and political implications of Kyoto Protocol on Latin American and other developing nations,” which could then be turned into commentaries that were “placed with key U.S. and Latin papers.”

In this pre-digital era, Atlas Network conceived the seminars as global distribution hubs for talking points, data, and narratives attacking the legitimacy of climate treaties. It explained to Exxon in a 1998 memo that one of its institutes in Latin America had produced a Spanish translation of a booklet by the U.S. climate denier Fred Singer, titled “The Scientific Case Against the Global Climate Treaty,” which it planned to distribute at the Argentina workshops.

Singer’s booklet claimed “there is no significant scientific support for a global ‘threat’ of climate warming,” and that “developing countries will suffer” from any global treaty “since their well-being and economic stability depend on international trade and general world prosperity.”

Atlas expected participants at the workshops to produce new papers, which it would then distribute “all over South America, including Mexico, and send them over to China and India, as well.”

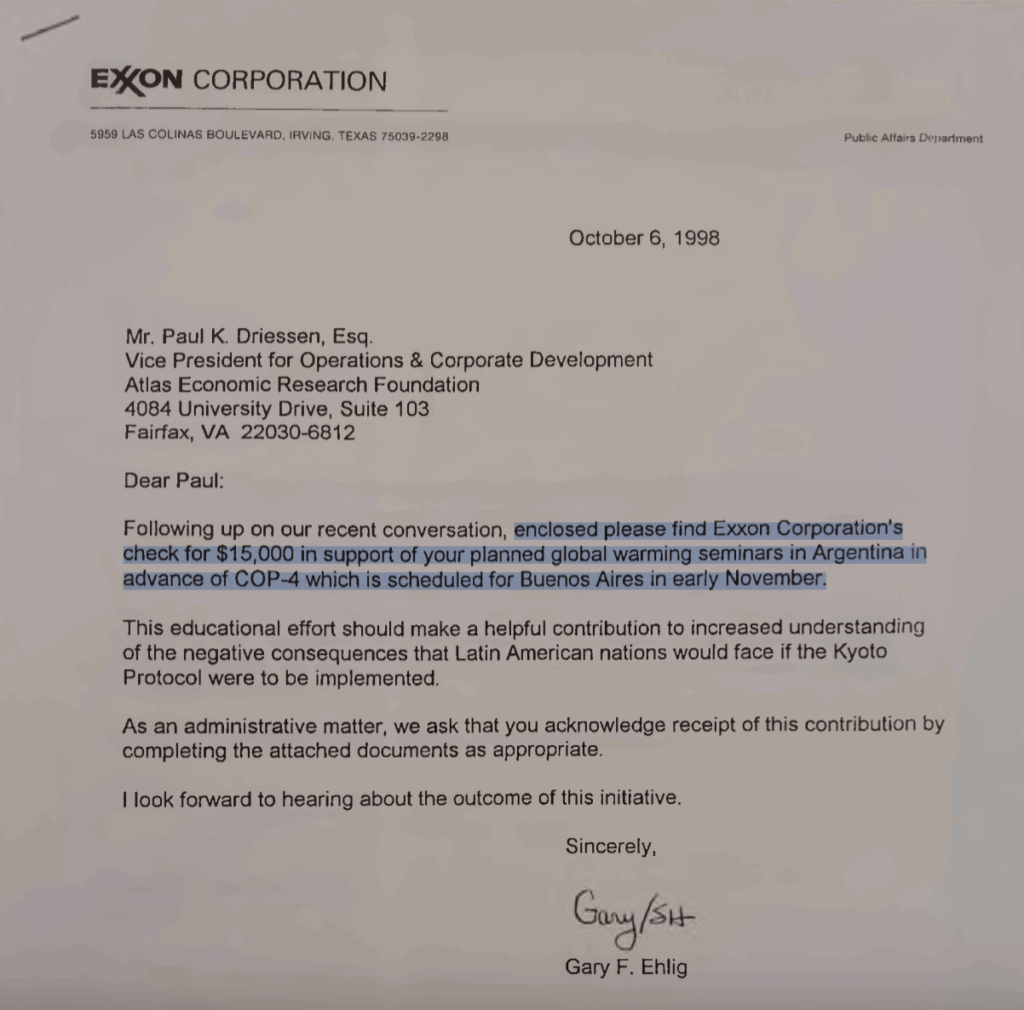

Exxon signed off on the plan and on October 6, 1998, mailed an additional $15,000 to Atlas “in support of your planned global warming seminars in Argentina in advance of COP-4.” The letter, authored by Exxon executive Gary Ehlig, predicted the seminars could lead to “increased understanding of the negative consequences that Latin American nations would face if the Kyoto Protocol were ever implemented.”

He added, “I look forward to hearing about the outcome.”

‘Wouldn’t Have Been Obvious’

Exxon explained in its correspondence that it was eager to support Atlas Network groups abroad because the company already felt like it had the political and communications infrastructure in place to protect its interests at home. “We are comfortable with the support we provide to US-based organizations and on US-related issues,” the company told Atlas Network in a 1997 letter.

By this time Exxon already had a track record of creating and spreading climate disinformation, even though its internal scientists, from the 1970s onward, had made highly accurate predictions about future warming caused by fossil fuels.

Exxon was a founding member of the Global Climate Coalition (GCC), a lobby and communications group representing fossil fuel producers, automakers, and other large industrial companies. Throughout the 1990s, the GCC ran media campaigns attempting to convince the public and policymakers that human-caused climate change wasn’t real.

The Global Climate Coalition itself had doubts about the deniers it was promoting, with one internal document during this period describing the “contrarian theories” of global warming as “not convincing.”

Nevertheless, on the eve of the 1997 climate negotiations in Kyoto, the Global Climate Coalition successfully lobbied the U.S. Senate to pass the Byrd-Hagel Resolution, which banned signing on to an international climate treaty that gave any concessions to developing countries, such as more lenient timelines for lowering their emissions — in effect, leveraging a central geopolitical fault-line of the COP process to prevent the U.S. from taking leadership.

Exxon then joined with fossil fuel companies and climate denial organizations such as the George C. Marshall Institute to create a communications plan targeting media, policymakers, and teachers, disseminating a now-infamous memo in April 1998 stating that “victory will be achieved when average citizens understand uncertainties in climate science.”

Efforts like this reflected a deliberate financial calculation on the part of oil and gas producers, argued Milani, the Rio de Janeiro State University academic. “They are aware of the fact that we need to transition away from oil and gas, and the later we do this the better for them, because they’ll still make lots of money from it,” he said.

Six months after the “victory will be achieved” memo, six Latin American Atlas Network partners “sponsored a series of seminars, briefings and media interviews in five Argentine cities, to present information of global climate change science and economics prior to the COP4 summit in Buenos Aires,” according to an Atlas Network update to Exxon on the organization’s activities.

These events “drew several hundred people” to hear “several well-known specialists from USA” discuss the “global warming scare.” All in all, Atlas reported, “media coverage included 8 television and radio appearances, over 12 articles in newspapers and magazines, and 19 interviews.”

Atlas Network noted in an update to Exxon on its 1998 programs that a partner in Beijing, the Institute of World Economics and Politics, had translated Singer’s book into Chinese. Atlas Network was also sending materials about climate change to think tanks in India.

“Few of these accomplishments would have been possible without Exxon Corporation’s generous financial assistance,” Atlas Network told its benefactor.

Exxon itself was barely visible at the COP4 climate talks, recalled Kert Davies, a climate disinformation expert, who attended the 1998 Buenos Aires negotiations with the non-profit Ozone Action. Davies recalled walking the venue’s hallways to try and get a sense of who had come to push for the strongest climate deal, and who was there to obstruct it.

Exxon’s only representative inside the event was Brian Flannery, Davies said, and his affiliation to Exxon wasn’t included on the official list of COP4 delegates. That the oil company was financing efforts to obstruct the talks “wouldn’t have been obvious to anyone,” Davies said. “I think it was intentionally not obvious.”

Strategizing With Exxon

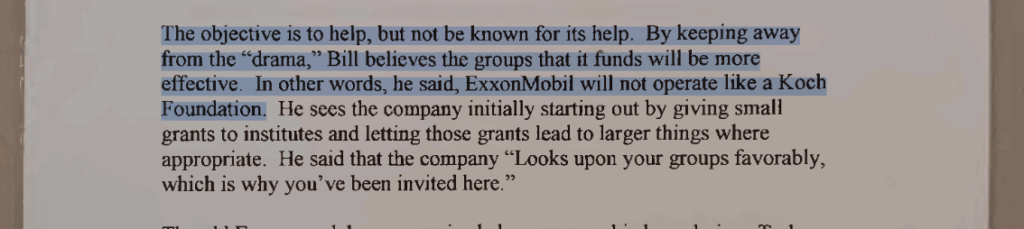

In mid-February 2000, Atlas Network’s Jo Kwong met with Exxon executives William Hale and Lynn Russo. The meeting was a strategy session on “advanc[ing] understanding of the international picture to see what is needed and how the company can ‘sensibly’ help,” according to an internal Atlas Network update submitted by Kwong.

Hale stressed during the meeting that Exxon had to have anonymity in its financing of Atlas groups and programs. “The approach has been behind-the-scenes, intentionally not seeking public kudos for its efforts,” he said. Hale also explained that this was a strategic choice. Exxon’s goal was “to help, but not be known for its help,” according to the update. “By keeping away from the ‘drama,’ Bill believes the groups that it funds will be more effective.”

In a follow-up letter to Hale after the meeting, Kwong said she “felt very honored” that the Exxon executive made time in his busy schedule for “so many hours” of strategizing with Atlas, and expressed her admiration for Exxon’s “commitment to furthering our joint interests.”

Kwong wished Hale, who was transitioning out of his role as an Exxon liaison with Atlas, “good luck in your new position at the company.”

In his new role working on “Communications and other public relations,” Hale would be helping to create “advertorials in the New York Times,” according to the Atlas update.

The following month, Exxon ran a now-infamous full-page advertorial in The Times headlined “Unsettled Science.” In the advert, Exxon took the position that “it is impossible for scientists to attribute the recent small surface temperature increase [in the atmosphere] to human causes” — even though years of high-quality internal climate research had found otherwise.

Five months after the meeting with the Exxon executives, Kwong went on a media and speaking tour in Argentina. The tour’s “major objective was to introduce the concept of free market environmentalism,” Kwong explained in a 2000 trip report for Atlas Network.

During talks hosted by network partners Fundacion Global and Fundacion Libertad, Kwong delivered this message to business leaders, government officials, policymakers, and environmental groups. She also gave “several press interviews with newspapers and television.”

Kwong summarized her main takeaways from the trip, saying that the reporters she encountered in Latin America invariably wanted to hear her views on whether to prioritize environmental protection or economic growth. “They were very surprised to hear my response: that countries must be rich before they can invest in the environment — that environmental amenities are a luxury good,” Kwong wrote.

This free-market environmentalism was, Kwong said, “quite the contrary to everything else they have heard.”

More than 25 years later, with global temperatures rising to historic levels and another key climate summit on the horizon, Bjørn Lomborg would echo essentially the same message.

‘Achieve Quick Results’

During September’s Climate Week in New York City, Lomborg authored an op-ed for the New York Post in which he described the global climate fight as an intractable stalemate, framing it as “rich-world elites obsessed with climate change versus developing nations battling poverty, hunger and disease.”

Climate experts say Lomborg’s divisive attacks on climate policy are propaganda designed to dampen enthusiasm among the public and policymakers for effective action to slow the climate crisis. The Danish economist has referred to these charges as a “smear.”

In Brazil, the same messages are being amplified by Leandro Narloch, an author and influencer with more than 100,000 followers on Instagram.

In an August episode of the Brazilian podcast Tubacast titled “COP30 — What’s Going To Happen Is Terrible,” Narloch launched into a familiar populist jab at climate conference delegates, criticizing the emissions released from their flights to the talks. “I also love parties, I love free flights, I love hotels, I love feeling like I’m part of the enlightened, but damn it’s kind of hypocritical,” he said, according to an English translation of his remarks.

Narloch and Lomborg’s paths crossed while Lomborg was in Brazil, at an intimate dinner with other free-market advocates such as Wagner Lenhardt, executive director of the Atlas Network partner Instituto Millenium, and Antonia Tallarida, president of Instituto de Formação de Líderes de SP, another Atlas partner. Narloch told his followers afterwards that it had been “an honor” to dine with Lomborg, the “author of False Alarm and so many other books on the exaggerations of climate debates,” posting a photo of the smiling group squeezed into a restaurant booth.

Narloch himself recently published a book called “The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Environment,” and is using promotional appearances as an opportunity to attack the upcoming climate talks in Belém, Brazil.

Carlos Alexandre Da Costa, an economist who served in the Ministry of Economy under the far-right former president Jair Bolsonaro, also attended the dinner, and shared the same photo on Instagram.

As nice as it was to enjoy the “pleasant companies” of fellow activists in the free-market movement, he posted, the meeting was also an opportunity to strategize. “We came out with several concrete actions to promote these ideas and achieve quick results,” he wrote.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts