By Paul D. Thacker

Bayer, which now owns Monsanto, announced at the end of July that it will remove the harmful pesticide glyphosate — a “probable carcinogen” — from its Roundup herbicide products by 2023, as it continues to face mounting pressure from lawsuits about the product’s health impacts.

But while the spotlight has been on the pesticide chemical’s potential dangers, a 2019 trial against Monsanto revealed another tale of bad behavior and its use of glyphosate: a story of corporate efforts to target journalists and activists dedicated to reporting on the risks posed by Monsanto’s products.

And just recently, on July 28, France’s personal data protection agency fined the company $473,000 for “illegally compiling files of public figures, journalists and activists with the aim of swaying opinion towards support for its controversial pesticides,” according to France 24.

Monsanto’s campaign to target journalists and activists was ranked the second most neglected story of 2020 according to the nonprofit media watchdog Project Censored in its annual list of top 10 stories overlooked by mainstream media. This is despite the company’s campaign to undermine reports on its bad behavior dating back decades.

Part of Monsanto’s campaign utilized international business advisory firm FTI Consulting, which offers services for a wide range of sectors including energy and mining as well as agrochemical and petrochemical industries. FTI Consulting has a history of targeting reporters. In 2019, the company was caught spying on reporters and helping orchestrate an operation to denigrate Carey Gillam, a book author and contributing writer for The Guardian.

Understanding how firms like FTI Consulting operate is critical for reporters and concerned citizens who are trying to understand the strategies that corporations deploy to confuse the people about public health. Too often, people scrutinize science issues only if they fall within their narrow focus of interest: climate change, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, food. But corporate disinformation cuts across all these concerns, because the main objective is protecting profits, not advancing science.

And the case of Monsanto and FTI Consulting shines a harsh light on the hidden work these firms orchestrate behind the scenes to sow doubt and disinformation.

As Monsanto faced a crisis over sales of glyphosate, the company hired FTI Consulting to help them beat back critics and undermine reports that they sold an herbicide that caused cancer. While it’s unclear exactly what year the two companies began working together, what is known is that around the same time, FTI Consulting was doing similar subterfuge for ExxonMobil and other fossil fuel companies by running a website called Energy In Depth — on behalf of the Independent Petroleum Association of America — that attacks scientists and reporters, and promotes climate disinformation.

FTI Consulting’s work for Monsanto first came to light when a reporter covering a Monsanto trial in California in May 2019 noticed that a woman presenting herself in the courtroom as a freelancer for the BBC also stated on her LinkedIn page that she worked for FTI Consulting.

When I then reported on this story for HuffPost in October of that year, FTI said they were initiating an internal review of their procedures, while Bayer denied employing FTI Consulting to work at the trial.

This was not the first incident, however, where FTI Consulting employees had posed as reporters. Previously, FTI consultants working for Western Wire had tried to question an attorney representing communities suing ExxonMobil about climate change. Western Wire was launched jointly by the oil and gas trade association the Western Energy Alliance and FTI Consulting in 2017 as the “go-to source for news, commentary and analysis on pro-growth, pro-development policies across the West.”

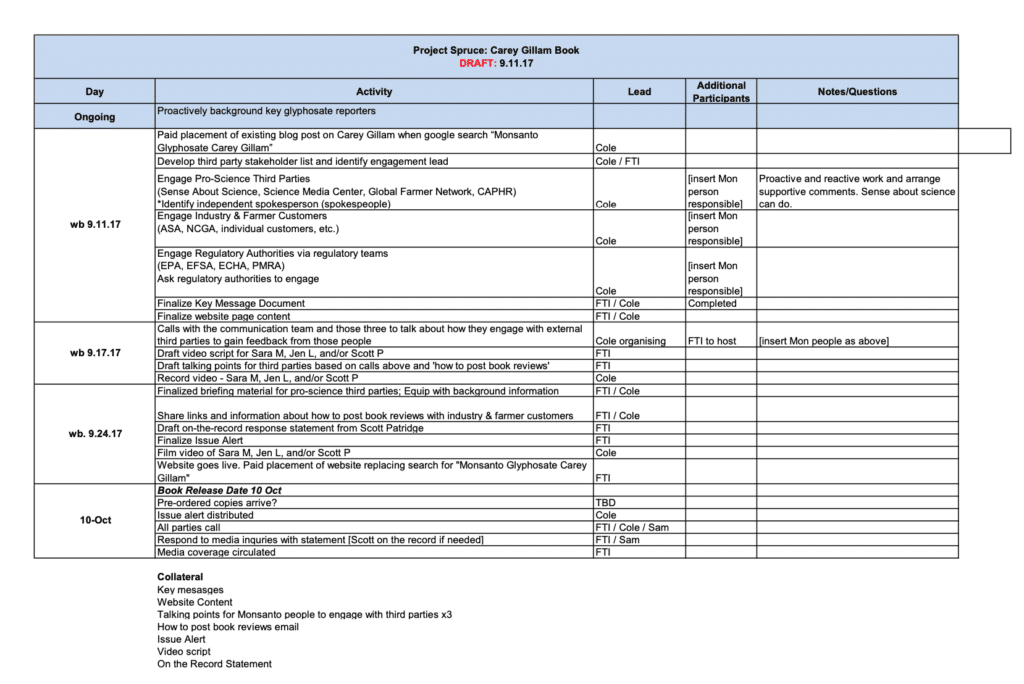

A few months after the FTI employee was caught in the courtroom, Monsanto’s internal documents became public during the trial. Writing in The Guardian, Carey Gillam reported on a Monsanto campaign called “Project Spruce” that outlined specific steps the company had been taking to harm the credibility of a book she had written in 2017 about glyphosate’s dangers and the steps Monsanto took to cover this up.

In one September 2017 email, an FTI employee notified Monsanto about several action items they were advancing, including providing a link to the book’s Amazon page, apparently so that Monsanto’s allies could post negative reviews. As Gillam reported, “Shortly after the book’s publication, dozens of ‘reviewers’ suddenly posted one-star reviews sharing suspiciously similar themes and language.”

The court documents also included a spreadsheet titled “Project Spruce: Carey Gillam Book” that detailed a sequence of specific actions the company was taking to undermine her book. The lead on many of these action items was FTI Consulting, whose work against Gillam included briefing Monsanto’s third party “pro science” organizations about the book, creating background materials on the book, helping to release a website to counter the book, and responding to media requests after the book was released.

While the work FTI Consulting did for Monsanto got a bit of attention after the court documents were released, major media outlets failed to highlight and explain the broader connection with FTI’s work on climate denial for the fossil fuel industry.

But as I reported in December 2019, for instance, documents and recordings of meetings by the Independent Petroleum Association of America (IPAA) showed the group was spending millions of dollars every year on Energy In Depth, a public outreach campaign that regularly attacked scientists and journalists critical of the fossil fuel industry. Most of Energy In Depth’s writers worked for FTI Consulting, and Jeff Eshelman, senior vice president of the IPAA told me that he had hired FTI Consulting several years back to run the site.

When contacted, FTI Consulting said that they could not discuss their work for clients. However, in 2014 FTI published a paper they presented at an oil and gas conference in Brazil. At the conference FTI explained that they used Energy in Depth to generate and guide media “behind the scenes” and claimed to have influenced hundreds of articles and opinion pieces. By running Energy In Depth themselves, FTI Consulting was allowed “to say, do and write things that individual company employees cannot and should not.”

FTI Consulting is just one of the many companies that provides disinformation for both the agrochemical and petrochemical industries. In fact, this overlapping work has been going on for decades, involving two groups most known for their work denying the dangers of climate change: the Heartland Institute and the Competitive Enterprise Institute.

For several years, the Heartland Institute published a monthly newspaper called “Environment and Climate News.” In March of 2000, they ran several stories that promoted GMO agriculture, while downplaying the dangers of pesticides and climate change. The author of one story in that edition of Environment and Climate News that promoted GMO agriculture was Francis Smith.

What the story did not note is that Francis Smith was employed by the Competitive Enterprise Institute, where she downplayed the dangers of climate change calling it “scare mongering.”

After examining these articles in Environment and Climate News, Harvard’s Naomi Oreskes explained that groups like Heartland and the Competitive Enterprise Institute form interlocking networks that promote unregulated or loosely regulated capitalism. “[T]his woman has no obvious expertise in climate science, no expertise in biotechnology,” Oreskes said of Smith’s writing on climate and agriculture. “This is a classic example of the pseudo expert, really an anti-expert. It’s a person claiming expertise and using that claim to refute genuine experts.”

Indeed, groups promoting disinformation for one industry often do the same for several others. Journalists covering beats such as climate, chemicals, or pharmaceuticals who become suspicious of an organization should check to see how that group handles information on other topics — including climate change. If they promote talking points for one industry, they often do the same for other companies as well. Because in the end, too many groups are hired to pretend to inform the public, while actually just protecting corporate profits.

This article has been co-published by DeSmog and The DisInformation Chronicle.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts