By the mid-1950s, the average American had roughly five times more discretionary dollars in their pocket than they’d had a decade earlier. Whilst this boosted the sales of goods, it also created a challenge: Durable products like cars and cookers lasted too long. So to keep revenues growing companies needed to come up with other ways to get people to spend their money.

To solve this problem, as Vince Packard documented in his 1957 book The Hidden Persuaders, the American advertising agency McCann-Erickson established a ‘motivational department’ staffed by five full-time psychologists. Nicknamed the ‘head shrinkers’, they developed a strategy called ‘psychological obsolescence’. It aimed to manipulate people into viewing their perfectly functional possessions as outdated and nudge them into an endless cycle of wanting more.

Fast forward to today, and the pollution caused by that desire creation has become a significant factor in climate breakdown.

In the UK — which has committed under the 2015 Paris Agreement to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 81 percent by 2035 — research shows that the average citizen’s carbon footprint would be about one-third smaller if not for the influence from advertising. This influence pushes us towards excessive consumption, which is particularly concerning when it comes to polluting products such as fast fashion, or high-carbon, cheap flights which encourage frequent flying.

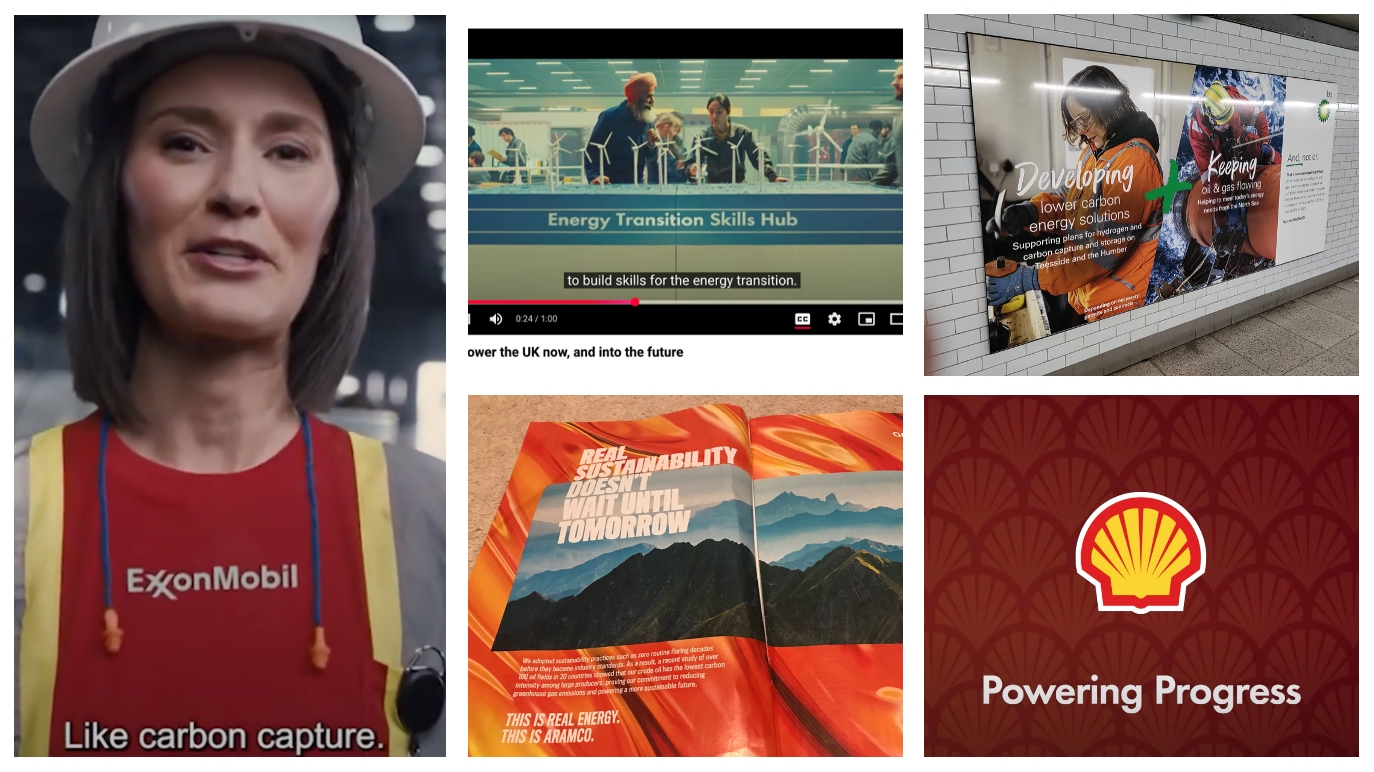

All this consumption is of course driven by fossil fuels, and this highlights another controversial issue in that adverts from oil and gas companies often allow significant misinformation to seep into the public’s subconscious.

With the COP30 climate talks due to open in the Amazon city of Belém next week, the Brazilian hosts’ decision to hire the New York-based public relations firm Edelman — closely tied to the oil industry — to craft “a strategic narrative” and manage media at the negotiations has thrown the climate contradictions in the advertising world into even starker relief.

So in the midst of a climate emergency, why are adverts that are designed to drive excessive consumption and skew our perceptions around fossil fuels, allowed? According to my research, the UK advertising industry — which regularly wins awards for its creativity, is led by regulatory bodies and trade organizations that are in the grip of vested interests, and operate in a culture of denial.

‘Mark Their Own Homework’

In the UK, the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) is tasked with regulating claims made by advertisers to ensure that adverts are ‘legal, decent, honest and truthful’. Yet the ASA (unlike similar regulators in other countries) is funded by the advertisers themselves, rather than the government. That means that it’s regulating the companies that pay its wages. As one MP commented, they “mark their own homework”. The ASA has also been criticised by the House of Lords for its lack of independence and accountability. One Peer said: “the code-writing, administration, appointments and funding [of the ASA] are entirely in the hands of the advertising industry… it is not accountable to anyone outside the industry — indeed, it is hermetically sealed.”

When it comes to regulating potentially misleading adverts for fossil fuels, the ASA acts at a snail’s pace, often taking six months or more to decide whether or not to ban an advert. This means that the advert is allowed to air whilst this prolonged decision-making goes on, spreading misinformation. The ASA’s review process remains opaque.

Rulings are at times inconsistent. For instance, in early 2025, the ASA banned social media adverts for French oil and gas giant TotalEnergies, which featured renewable energy visuals and information, but failed to state that TotalEnergies’ operations remained mostly fossil-fuel based. Yet the ASA cleared a similar advert for Shell, which also prominently featured renewable energy imagery and messages, but also briefly showed some small print at the bottom detailing Shell’s proportion of investments in fossil fuels. Nevertheless, the overall impression and tagline was misleading in suggesting that Shell was ‘powering progress’. The ASA’s codes state that all information on an advert must be easily understood by a lay person, and the small print referencing Shell’s fossil fuel investments clearly did not meet that criteria.

Overall, the ambiguity and lack of consistent application of the ASA’s advertising codes means that fossil fuel advertisers are able to continue to suggest they are investing in a renewable energy future. This is clearly untrue, as big oil and gas majors are rolling back climate targets and continuing to ‘drill baby drill’.

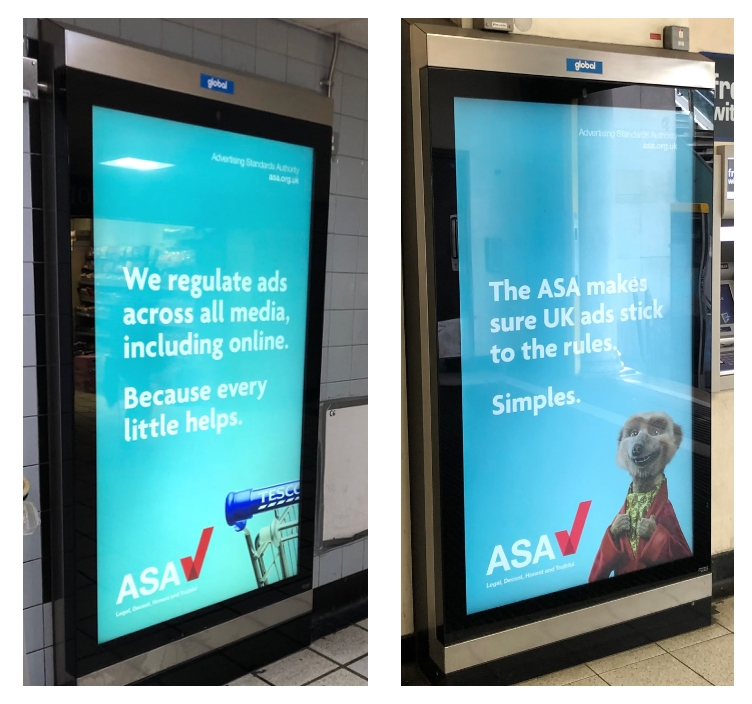

In the summer of this year, the ASA started to run its own adverts, promoting itself as an effective regulator. In July, on the very day that the UK Parliament held its first debate on to ban fossil fuel advertising, ASA adverts appeared in London Underground stations. These adverts may have been an attempt to reassure any passing politicians that there was no need to change the laws around the regulation of fossil fuel advertising.

However, even the ASA’s own adverts don’t appear to be that truthful. For example, the adverts stated that the ASA ‘regulate ads across all media.’ But that’s not the case: There is a whole list of exemptions, such as political advertising and point of sale that the ASA does not regulate.

The adverts stated that the ASA ensure that adverts ‘stick to the rules’. Again, untrue: The regulator can only begin to address a potential ban once an advert is made public, and therefore only has retrospective powers.

It seems the ASA’s own advertising might therefore fail to meet its own codes. Complaints submitted to the ASA about these particular adverts received a response which stated that there is no process in place for regulating its own potentially misleading advertising. This highlights a key flaw in the ASA’s self-regulatory position and leaves no recourse for the public to demand accountability.

Contradictory Claims

The advertising industry trade group, the Advertising Association (AA), does not focus on the regulation of misleading adverts but exists to represent the industry and its members. The organisation, however, does not want to engage in discussion of the role advertising might play in promoting excessive consumption. My research on institutional change in the advertising industry found that the AA avoids recognising that adverts for highly polluting goods and services might harm the environment through a unique strategy of denialism, oddly insisting to some audiences that advertising is highly effective and to others that it is highly ineffective.

For example, to the bafflement of its industry audience, the AA claims that in around 88 percent of cases advertising is ineffective at growing markets or increasing sales, citing its ‘investigations’ of the academic literature and its own data. In stating this as a fact, the AA avoids the need to account for emissions arising from the increased consumption driven by advertising — known as ‘advertised emissions.’ If adverts are ineffective, and therefore don’t increase consumption, there is no need to actually try and measure that consumption, the AA maintains. Any attempt to evaluate advertised emissions is therefore futile, the AA insists, and the industry will never get to net-zero carbon emissions by measuring it.

However, the group presents a different narrative to government officials and other audiences when it needs to prove advertising’s value to the UK economy. The AA portrays the advertising industry as a highly relevant and effective sector, providing, a £42-billion asset to the UK economy that adds £6 to the country’s Gross Domestic Product for every £1 spent.

Can both things be true — that advertising is both effective and ineffective? Likely not, and there is ample evidence to prove adverts are highly effective at influencing behaviour and increasing consumption. But by denying this, the AA can argue against potential restrictions or advertising bans, thus retaining their membership fees from big brand advertisers as well as advertising agencies. As one senior advertising professional I interviewed for my research put it, the AA had been “captured by the highest-paying clients.”

This practitioner and others I spoke to said they want their trade body to recognise both the need for restrictions on adverts for products that pollute, especially fossil fuels, and for advertised emissions to be recognised. The interviewees said that no matter how hard they pushed for change, the AA mostly ignored their views — which goes against the AA’s mandate to act as ‘the link between practitioners and the politicians and policymakers whose decisions impact the sector.’

The AA’s Ad Net Zero (ANZ) initiative is its nod to sustainability. Borrowing pillars from other initiatives, it acknowledges the need to tackle the ‘operational emissions’ generated by advertising agencies, which include emissions from staff flights, or from producing the energy needed to produce adverts. However, the initiative completely fails to address advertised emissions or the industry’s work with fossil fuel majors. The initiative also has an Ad Net Zero Awards scheme for adverts that drive behavioural change, such as by promoting recycling or reducing food waste. What is not mentioned is that around three-quarters of agencies that won an ANZ award in 2024 also had contracts with fossil fuel clients. One professional I interviewed said the awards were not substantial: “It’s literally just for an agency to say, “look we’re doing something around [sustainability]” …and so it’s kind of an agency greenwashing itself.”

In 2022, the House of Lords took an interest in how advertising impacts the climate. It called on the AA to give evidence on how advertising might advance the government’s climate agenda. The AA, however, did little beyond promoting its ANZ awards scheme. The Peers were unimpressed, with one commenting that the AA’s submission for the meeting was: “extremely superficial, [emphasising] that the adverts did not make any difference and so on and so forth. That rather belies the fact that this is a £32 billion business. It seemed to me, from the submission you put in in the first place, that you were not fundamentally engaging with this at all.”

It’s clear that some of the professionals I spoke with for my research also don’t think the AA are engaging with the issue. One said: “I do wonder how much the AA is responsible for this too… because they are creating the space where that’s the outlet where you go” [to try and change the industry], “but they’re not doing anything. I think there needs to be a BBC Panorama undercover.”

‘Complicit in the Delay’

So if the institutions which are meant to regulate and represent advertising are failing, what about the advertising agencies themselves?

All six of the largest global holding groups — Dentsu, Havas, Interpublic Group, Omincom, Publicis, and WPP — have contracts with fossil fuel clients, which means that many of their UK agencies service fossil fuel briefs.

In my interviews, senior employees in some of these organisations described a range of interventions they had used to move their agencies away from taking on polluting projects, such as appealing directly to their CEOs to drop fossil fuel clients — in one case, with an open letter signed by over 800 staff.

In return, some were threatened with dismissal or other punitive measures, such as having their activities monitored and being asked to take down personal LinkedIn posts about climate change, or being told to “pull back on the climate work”.

One reason for this pushback could be the risk of loss of any revenue from oil and gas clients, and research from DeSmog uncovered that some directors of global advertising agencies had private ties to companies which serviced the fossil fuel industry. It would seem that hidden vested interests exist at every level in the advertising world.

Whatever the reason for the resistance from agency CEOs, it took a significant emotional toll on employees. “I was made redundant and I’m absolutely certain it’s because of the work that I was doing,” one professional told me. “On a personal level, I ended up in a very, very, dark place. After that, it took me probably at least six months to recover.”

Another said that after her agency refused to stop working with fossil fuel clients she quit her job because she could no longer handle the stress of working on polluting briefs.

One professional laid it out clearly to me: “We are complicit at the moment as the advertising industry. We are complicit in the delay. We target politicians and financial decision-makers to make them think that fossil fuel clients are part of the solution, like, that’s in the briefs.”

An Industry Transformed?

Whilst change is lacking inside the industry, external pressure is mounting. For example, a recent petition backed by Chris Packham, the wildlife presenter, to ban adverts for fossil fuels, gained over 110,000 signatures, enabling the parliamentary debate in July. The result (summarised here) was mostly cross-party support, with many MPs discussing the range of benefits of banning adverts for oil and gas products and likening the move to tobacco advertising bans that have been broadly accepted as benefiting the public. It was a pivotal first stage, showing the increasing potential for restrictions on adverts that manipulate the public’s perception of the climate crisis and frustrate net zero goals.

Advertising restrictions at regional level are coming in fast, with many UK councils banning adverts for polluting goods and services on their estate. Support globally is growing, with U.N. special rapporteurs calling for restrictions, following on from a call from U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres in 2024 which asked advertising agencies to “stop acting as enablers of planetary destruction“ by representing oil and gas majors. The list goes on, with countries banning adverts for fossil fuels as well as fast fashion. Health organisations, cultural institutions and a swathe of European consumers all support a move away from fossil fuel advertising as well as for a range of polluting products. Specialist independent groups such as Ad Free Cities, Badvertising, Purpose Disruptors, Clean Creatives and Creatives for Climate, and many more are all working effectively at supporting the industry towards a clean transition.

We’ve come a long way since Vance Packard’s head shrinkers. My sense is that we’ll look back at adverts for fossil fuels in the same way we do now for smoking, in awe that we ever encouraged it.

In a worsening climate crisis and to achieve net zero goals, it is crucial that the UK government understands the power of advertising to influence behaviour and perception. It should recognise the vested interests and lack of accountability that persists in the UK advertising industry. If the lack of institutional transformation within the sector persists, then it’s much more likely that top-down restrictions, such as bans on adverts for polluting products, will be required at the national level.

Change is possible. The regulator, the ASA, could update its codes to tighten up on greenwashing in fossil fuel adverts and be more proactive on the complaints it receives. The funding structure could change to allow true independence and align with ways other countries run their regulators. The trade body, the AA, could easily recognise advertised emissions. It could also propose sensible guidance for agency members to gradually disengage with fossil fuel clients, future-proofing creative jobs in the face of any potential bans. None of these interventions are all that difficult.

If these steps are not taken, however, the trade and regulatory bodies will remain outdated, adrift in the climate change narrative, and grasping at unrealistic storytelling. There really is no need to continue in denialism and delay, swimming against the tide of climate science. The time has come for the UK advertising industry to ditch its vested interests, fully transform, and play a meaningful part in climate action.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts