The global advertising giant Interpublic Group (IPG) is facing allegations by staff that its rebrand of the world’s largest oil company violated a pledge to avoid work that could worsen the climate crisis.

Documents obtained by DeSmog show that a group of IPG’s London-based agencies created campaigns designed in part to convince government policymakers that Saudi Aramco was developing climate solutions — even as it planned to invest hundreds of billions of dollars in new oil and gas.

A dozen current and former IPG employees said the strategy appeared to breach IPG’s commitment to avoid projects “aimed at influencing public policy that seeks to extend the life of fossil fuels.” CEO Philippe Krakowsky had announced IPG’s policy as “a first for the industry” in September 2022 amid growing internal calls for him to act on climate — including a letter signed by more than 800 staff urging the agency to drop polluting clients.

A version of this article has been published by the Financial Times

Scientists agree that the world must rapidly transition away from oil, gas, and coal. Burning these fossil fuels is the main cause of climate change, which is fast creating an increasingly uninhabitable world of deadly droughts, floods, heatwaves and storms.

But the documents show that the underlying goal of IPG’s work for Aramco was to bolster the state-owned Saudi oil company’s “license to operate as part of the future energy landscape” — oil executive-speak for business as usual.

“This Aramco work was in direct contravention of [IPG’s climate] policy,” said one former employee who — like others quoted in this story — declined to be named for fear of professional repercussions. “Everything IPG does for its fossil fuel clients is aimed at influencing key decision-makers in corporate and political spheres, and making the fossil fuel revenue party last for as long as possible.”

Employees also said IPG appeared to have breached a separate element of the policy that requires new energy clients to be aligned with the Paris climate agreement when it signed QatarEnergy, Qatar’s state-owned oil and gas company, in April 2024.

Amid a growing global movement to ban fossil fuel advertising, the documents provide a rare inside view of how advertising and public relations agencies delay climate action by portraying polluters as greener than they actually are.

IPG’s work for Aramco also shows how easily pro-climate rhetoric from top industry executives can fall victim to growing commercial pressures in adland.

“I’m not aware of any processes that are in place that would monitor the nature of the work that we do on behalf of these [fossil fuel] clients and ensure any adherence to the [climate] policy — as you can see with Saudi Aramco,” said a director at one IPG agency.

‘A Structural Lie’

IPG helped Aramco launch a rebranding campaign in 2021 under the tagline “Powered by How”, which sought to portray the oil giant as a global innovation company. The campaign used tactics from TV ads and podcasts, to sports sponsorships and interactive events, to associate Aramco with apparently pioneering technological solutions to the climate crisis.

The rebrand aimed to whet foreign investor appetite for a planned sale of Aramco shares that ultimately took place in 2024, raising $12.35 billion. The money was intended to fund Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman’s Vision 2030 plan to promote Saudi Arabia as a cultural, economic and sustainability superpower.

Even as IPG worked to portray Aramco as part of the climate solution, Aramco was planning to invest more than $230 billion in fossil fuel exploration and production between 2024 and 2030, according to consultancy Wood Mackenzie — more than any other company.

Away from its advertising and PR campaigns, Aramco executives were saying the quiet part out loud. In March 2024, Aramco CEO Amin Nasser told fellow oil and gas executives at the CERAWeek conference in Houston, Texas, that the world “should abandon the fantasy of phasing out oil and gas.”

As a state-owned oil company, Aramco’s positions are effectively statements by the Saudi government, which has aggressively blocked progress at international climate negotiations for decades. Nevertheless, in a 2023 presentation for Aramco, IPG said it would evolve the Aramco brand to “support positive perceptions” of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and “align with [its] objectives”.

IPG’s work for Aramco amounted to “engaging in a structural lie,” said Abdullah Alaoudh, a senior director at Washington DC-based advocacy group Middle East Democracy Center.

“By working on these advertisements you are making it easier for [the Saudi government] to pay for a good reputation instead of complying with the principles of human rights and the environment,” Alaoudh said.

IPG updated its statement on fossil fuel-related lobbying in 2024 to apply only to work for trade groups — not individual companies. However, the allegations of a violation relate to work carried out for Aramco when the original policy was still in force.

IPG’s rival Omnicom is currently acquiring IPG in a $13 billion deal designed to consolidate services and reverse declining profits at the two New York-based companies.

IPG did not respond to multiple requests for comment. The company says on its website that it has turned down potential clients “on multiple occasions” since adopting its climate policy.

Omnicom did not respond to a request for comment.

Aramco declined to comment.

‘Fuels of the Future‘

IPG devised the Powered by How campaign at a critical moment for Crown Prince Mohammed’s plans to transform Saudi Arabia’s global image.

The Kingdom’s reputation had been heavily damaged after its agents murdered Saudi dissident Jamal Khashoggi, a Washington Post journalist and U.S. resident, at the country’s Istanbul consulate in October 2018. According to U.S. intelligence reports, Prince Mohammed — often known by his initials MBS — personally ordered the execution, in retribution for Khashoggi’s criticism of the Saudi regime. Prince Mohammed has always denied the allegations.

The Saudi government nevertheless took Aramco public the following year, raising $25.6 billion in the world’s biggest share floatation.

But concerns over conflict in the Middle East, future oil demand in a world transitioning to cleaner energy, and the Saudi state’s heavy involvement in the company weighed on international investors — coveted by Prince Mohammed for their cash and political cachet. Nearly 80 percent of the shares were sold to domestic buyers.

So with Vision 2030 projected to cost trillions, plans were soon made for a second share offering.

In late 2020, Aramco asked IPG to develop a strategy to “maximise value recognition” among investors in the U.S., China, UK, Germany, France, Singapore, and Hong Kong, the documents show.

IPG — which has worked with Aramco since at least 2012, according to DeSmog research — was an obvious choice of partner.

The firm has a long history of working with the fossil fuel industry. Its dozens of subsidiaries currently hold at least 59 contracts with fossil fuel producers or distributors, including U.S. oil majors ExxonMobil, Chevron, and ConocoPhillips, according to the documents and online sources.

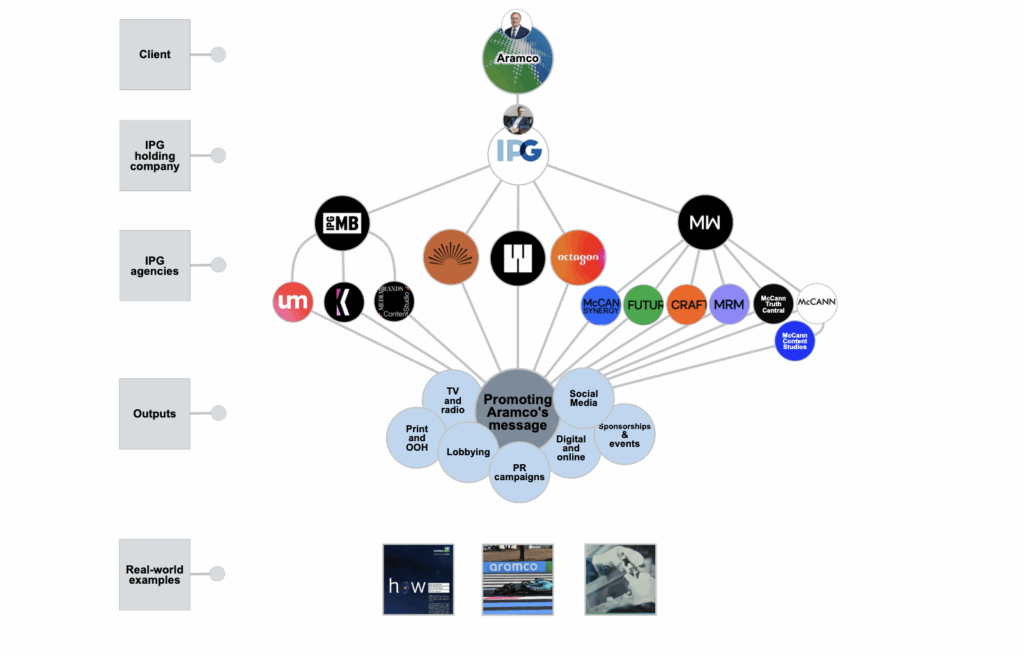

For its Aramco work, IPG has grouped up to 200 staff from 15 agencies — mostly based in London — into a bespoke Aramco team known internally as “Well7”, according to the documents and IPG sources. The unit is named after the Dammam No.7 oil well, where commercial quantities of oil were first discovered in Saudi Arabia in 1938.

The creative teams charged in 2020 with improving Aramco’s reputation among foreign investors faced a conundrum, however. Growing awareness of the climate damage caused by burning oil and gas, and support for the energy transition, had raised questions over Aramco’s prospects in a “climate concerned world”, one planning document acknowledged.

‘Innovation Company’

To solve this dilemma, ad executives at McCann Worldgroup, IPG’s creative division, spent more than a year devising Powered by How.

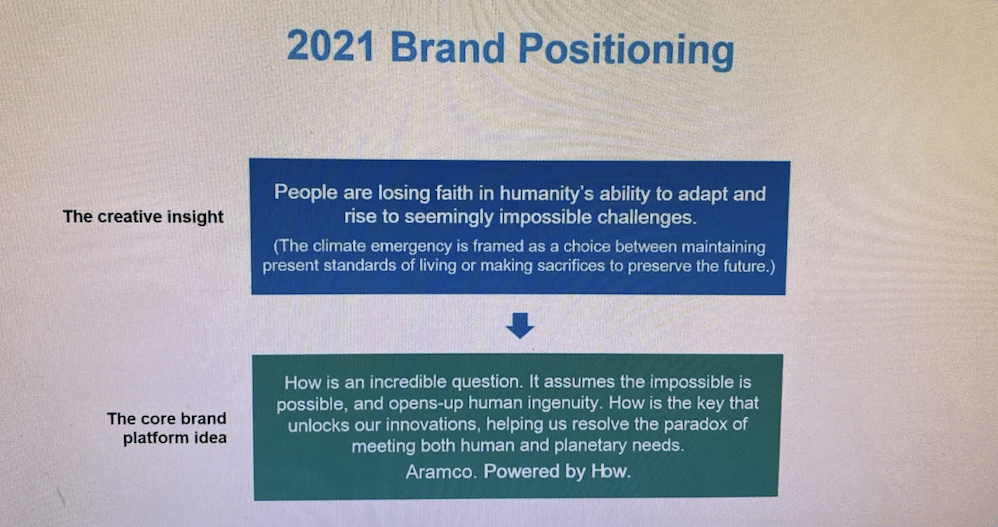

In a 2021 presentation laying out their strategy, McCann Worldgroup consultants said that the climate crisis is too often “framed as a choice between maintaining present standards of living or making sacrifices to protect the future.”

The consultants explained that a tagline based on the word “how” would play well for Aramco because the word “assumes the impossible is possible” — helping to imply the company had climate change under control.

Daniele Pulega, a former global creative director at McCann Worldgroup, said on his personal website that the campaign “repositioned Aramco from a Saudi oil company to an international innovation company” ahead of the 2024 share sale.

Pulega added: “Aramco, the world’s largest integrated oil and gas company, has been under much scrutiny over the last decade. And its future has been much questioned….[They] wanted to reintroduce their brand to the public to change perceptions and build investor confidence, committed to answering those big questions that the future of our planet depends on.”

Pulega — whose website is no longer online — did not respond to a request for comment.

“The strategy is selling a fantasy world,” said a former McCann Worldgroup brand strategist who reviewed the documents. “They’re turning Aramco into Willy Wonka here: ‘We will enable you into this magical future where anything is possible.’”

Meanwhile, IPG Mediabrands — the network of IPG agencies focused on buying ad space for clients and helping them reach their audiences — created multiple presentations on ways to aim Powered by How and similar messaging at policymakers.

The presentations suggested targeting this audience — as well as academics, environmental activists, and others — because their attitudes towards Aramco could influence investors ahead of the next planned share offer.

IPG Mediabrands said Aramco’s communications should imply that the company “create[s] wealth…that’s human as well as financial” and “act[s] as stewards for the next generation.”

IPG Mediabrands did not respond to a request for comment.

Some of the ads produced off the back of this strategy referenced growing global energy demand, echoing a trope long-used by the fossil fuel industry to justify greater investment in oil and gas. One YouTube video published in 2022 — which has 83 million views — asks: “How can we deliver energy to a world that can’t stop?”

“The strategy here is to reassure investors and policymakers that fossil fuels are so unbelievably important for wealth creation that they should not feel guilty about the side effects,” said Professor Dr Joyeeta Gupta, a social scientist at the University of Amsterdam and former co-lead author for the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Former and current employees told DeSmog that the targeting of policymakers should have ended when IPG introduced its climate policy in September 2022.

Yet in a presentation profiling Aramco’s target audiences for 2023, IPG noted the importance of reaching policymakers who had “made policies in local, regional, or national government bodies” in the prior 12 months.

In an October 2023 presentation on branding, IPG said that creating a “perceived positive overall contribution to society” among this audience would help Aramco “secure a license to operate as part of the future energy landscape.”

Another presentation from that month listed challenges facing Aramco — such as a “negatively evolving regulatory landscape”, an apparent reference to prospects of tougher government action to curb planet-warming carbon emissions — and how IPG proposed to “future-proof” the company’s brand.

The strategy appeared to work.

Aramco’s second public share offering in June 2024 — which took place after Powered by How had been running for two-and-a-half years — was widely seen as more successful than the 2019 listing. Shares sold out in just a few hours, and foreign investors made up 58 percent of the buyers — up from 23 percent in 2019, AFP reported.

“That is a vote of confidence for MBS,” David Rundell, a former U.S. diplomat who spent most of his career in the Middle East, told Bloomberg at the time.

‘Mental Gymnastics‘

Powered by How relentlessly promoted Aramco’s preferred climate solutions in the media, despite a lack of evidence that they can become economically viable or technologically effective at the scale companies such as Aramco are promising.

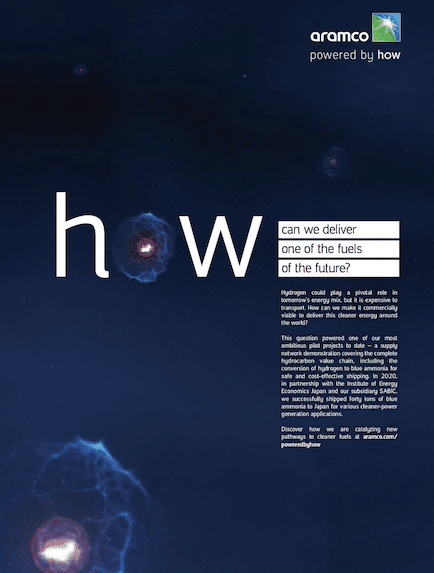

A four-page Aramco ad in Time magazine’s “Best Inventions of 2022” issue described hydrogen derived from natural gas — termed blue hydrogen — as “one of the fuels of the future”. In a video published on Aramco’s YouTube channel in 2023, a voiceover explained that carbon capture technology could “square [our] relentless innovation with a responsibility to the world around us” over cinematic shots of Aramco engineers.

In 2023, global news agency Reuters’ in-house advertorial agency Reuters Plus produced a series of Powered by How podcasts that featured Aramco executives praising such technologies. Similar Aramco content and ads appeared in major newspapers including the Financial Times and Le Monde.

However, in November 2024, Nasser, the Aramco CEO, said the company might use its new natural gas investments to produce planet-heating liquefied natural gas instead of blue hydrogen, due to rising costs.

To date, Aramco has no commercial-scale blue hydrogen production plants, and the only carbon dioxide that the company currently captures — at the Hawiyah gas plant in the east of Saudi Arabia — is used to extract hard-to-reach oil at its Uthmaniyah reservoir.

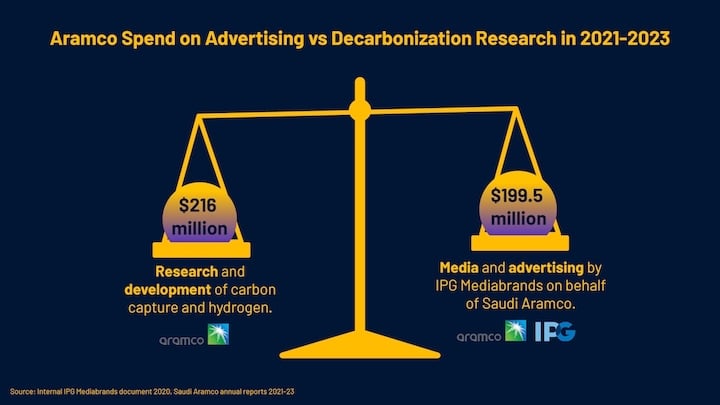

Aramco has spent almost as much money on advertising these technologies in recent years as it has on researching how to deploy them.

Between 2021 and 2023, Aramco invested the vast majority of its $112 billion in capital expenditures on oil and gas. During the same period, the company spent a total of $216 million on the research and development of carbon capture and hydrogen fuels, according to its annual reports, and gave IPG an advertising budget of nearly as much — just under $200 million — according to an internal IPG briefing document from late 2020.

The Powered by How strategy was “Orwellian,” said Ben Freeman, a director at Washington-based think tank the Quincy Institute.

“You can spin the narrative however you want, but at the end of the day Aramco is the world’s largest oil company,” said Freeman. “The mental gymnastics you’d have to work through to translate that into some sort of pro-climate firm are just absurd.”

‘Sin Clients’

IPG agencies know that working with the fossil fuel industry is increasingly seen as unethical.

In one internal presentation from 2023, IPG’s creative advertising division McCann Worldgroup referred to its oil and gas contracts — along with its tobacco and gambling relationships — as “sin clients”.

But even as employees have voiced their concerns, executives have doubled down on justifications for keeping fossil fuel clients.

In a September 2022 memo to staff announcing the launch of the climate policy, Krakowsky, the IPG CEO, echoed a common ad industry talking point: “We think it is important to be in the room, working with clients that provide energy and basic services essential to people’s lives — and to positively impact their business transformation journeys.

“And while some of the work that we have contributed to in the past would not live up to our current standards, we are committed to aligning all future work on behalf of these clients to our company’s sustainability values.”

One week after Krakowsky’s comments, some 800 of IPG’s 50,000 staff, including several managing directors and partners, signed the letter asking him to go further and “commit to a fast and transparent transition away from fossil fuel clients.”

The following month, Chief Sustainability Officer Jemma Gould assured employees in a meeting that senior leadership were open to discussing a transition plan, according to notes that later circulated among the hundreds of signatories.

Gould and Krakowksy did not respond to requests for comment.

However, soothing words from the C-suite have rung increasingly hollow to IPG employees.

Many were frustrated that a “climate impacts” review process introduced as part of the new policy only applied to prospective clients — meaning the company would not cease working with major polluters on its existing roster, like Aramco.

And even the review process for new clients appears to have holes. An April 2024 email obtained by DeSmog, sent to staff at IPG’s New York-based subsidiary UM, celebrated winning QatarEnergy as a client.

UM is a media-buying agency, meaning it provides strategic advice on how its clients — like global coffee brand Nescafé — can reach specific audiences, and sells them the ad space to do it.

UM employees said that any deal with QatarEnergy would appear to breach a commitment in IPG’s climate policy to only accept new oil and gas clients that plan to reduce their emissions in line with the Paris Agreement target to limit the global temperature rise to 1.5°C (3.6°F).

QatarEnergy aims to increase its production of planet-heating liquefied natural gas by 84 percent by 2031 relative to 2023 levels, according to financial think tank Carbon Tracker — an expansion scientists say is incompatible with the 1.5°C goal.

QatarEnergy did not respond to a request for comment.

“It’s a total violation of the [climate] policy,” said an ex-employee who recently left UM and worked for fossil fuel clients at the agency. “I’d find it less troubling if they weren’t hiding behind ‘values’, but this is clearly greenwashing.”

IPG has generally refrained from promoting its work for Aramco, QatarEnergy, and other fossil clients, both internally and externally. Several employees said this was to dampen staff dissent and ward off criticism from environmental groups — a significant sacrifice in an industry obsessed by awards galas.

“These clients are generally kept very quiet because leadership knows the work is controversial,” said another former UM employee. “While I was there we didn’t shout about what we were actually doing for these companies internally, let alone to the outside world.”

Other current and former IPG employees said the relationships with Aramco and QatarEnergy exposed the emptiness of the company’s public statements on climate change.

“It felt as though things were happening,” said a former employee who was involved in a staff-led climate initiative. “However, it now seems rather superficial. I don’t think the [climate] pledge is worth the digital paper it’s written on to be honest.”

Employees also fear that IPG’s acquisition by Omnicom — which has dozens of fossil fuel clients of its own — could see even IPG’s stuttering progress on climate wiped out. Omnicom does not have any public statements or policies designed to curb the impacts of its work for the oil and gas industry.

‘Profits at All Costs‘

In June last year, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres urged agencies to drop their fossil fuel clients, describing ad executives creating the campaigns as “Mad Men fuelling the madness.”

Activist group Extinction Rebellion has held protests at the offices of IPG’s rivals, including at the London headquarters of global holding companies WPP and Havas.

Meanwhile, more than 1,000 small to medium-sized ad agencies have signed campaign group Clean Creatives’ pledge not to work with fossil fuel companies.

Calls for governments to impose tobacco-style ad bans on fossil fuels are also growing louder. The UK parliament held its first debate on the idea in July, prompted by a petition signed by more than 100,000 people. Cities such as The Hague, Sheffield, and Edinburgh have introduced restrictions on fossil fuel advertisements in public spaces.

IPG and the other advertising giants — WPP, Publicis, Omnicom, Dentsu, and Havas — have made various commitments to reduce emissions from their own operations. But these “Big Six” companies that dominate the global industry have shown no sign of shunning oil and gas clients, or backing calls for ad bans.

Staff attempting to raise climate concerns internally say the money is still talking — especially at a time when tech giants are gobbling up ad revenues and AI-assisted marketing is threatening business models. Compounding the silence on climate, the Trump presidency is having a chilling effect on corporate consideration of anything other than the bottom line.

DeSmog was unable to independently ascertain the total value of IPG’s various contracts with Aramco across all 15 of the agencies that make up Well7, or of UM’s contract with QatarEnergy.

One of these agencies, McCann Worldgroup, held 18 oil and gas contracts worth $25 million in 2023 (about 1.5 percent of its total revenue), including a $9.5 million contract with Aramco, according to an internal presentation. This made Aramco McCann Worldgroup’s 14th most valuable contract, another document showed.

Employees said the media-buying agencies within IPG Mediabrands may be earning significantly more than McCann Worldgroup, because the former make commissions on the vast amounts of ad space they buy and manage for clients.

IPG employees also said that the company’s relationship with Aramco is highly valued because it has led to other lucrative contracts with the Saudi government — such as with Aramco’s Ithra cultural centre, chemicals company SABIC (now owned by Aramco), and the planned futuristic eco-city Neom, according to DeSmog research.

IPG’s leadership is under growing pressure to retain its existing business — not cut long-standing clients loose. The company reported that its pre-tax profits fell by more than 23 percent year-on-year to $218 million in the second quarter of 2025.

One former employee at ad agency McCann — a subsidiary of IPG’s McCann Worldgroup — said that their agency’s approach to fossil fuel clients was to “maximise profits at all costs, period.

“That means taking problematic clients and minimizing it, burying it, obfuscating it, and mischaracterising the work.”

Meanwhile, a report by London-based market research agency Kantar is clear: Aramco is now a more widely trusted and recognised brand than before the launch of Powered by How.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts